BETWEEN SEA AND FLAME

BETWEEN SEA AND FLAME, by Evan Dicken

Hummingbird ran. Branches whipped across her arms, the shouts of her pursuers eclipsed by the huffing gurgle of the thing tearing through the forest behind her. There was a loud crack as one of the Sea People fired his weapon, the shot tearing through the leaves nearby. Hummingbird flinched, surprised by the closeness of it. Usually, the Invaders’ matchlocks were woefully inaccurate, especially if the shooter was moving, but the weapons her pursuers carried were fast and precise, almost worse than the monster behind her.

Almost.

She stumbled to her feet, risking a glance over her shoulder. Although the creature was close, it was hard to tell just how close, as distance bent like a heat mirage around it. Hummingbird’s gaze slid across the creature, her eyes watering as she tried to focus on it. She caught a glimpse of many mouths, some wide as a caiman’s jaws, others small and delicate with pouting, childlike lips. It was as large as a peasant’s hut, but had no body she could see, just a mess of ungainly limbs. Hooks, hands, and talons tore at the earth, the trees, the air, dragging the creature forward with unsettling speed.

Blood pounded in Hummingbird’s ears, her legs weak as rotten wood. She ran on, wondering if her next breath would see her cast into Mictlan to be spread upon a scaffold to have her flesh scraped from her bones. It was a traitor’s fate, a coward’s fate, but Hummingbird had become both when she fled Lake Texcoco, leaving her Cuachicque sisters and her lord to die. Perhaps the creature chasing her would drag Hummingbird down to whatever watery underworld had spawned the Sea People, at least then she would be spared the shame of facing those she’d abandoned.

Trees gave way to empty air, the ground sloping sharply down into one of the many defiles that cut through the forests around Mount Mombacho. She tried to stop, loose stone and gravel skidding under her feet. For a moment, she hung over the edge, arms spread like a bird ready to take flight, but Hummingbird was not her namesake and the air raised no hands to steady her.

Falling, she managed to tuck her head before she hit the cliffside, turning what might have been a neck-snapping impact into a hard roll. Rocks dug into her quilted cotton vest and hide leggings, scraping fiery trails across her exposed skin. Fortunately, her weapons were tightly bound–her axe in its leather sheath and her macuahuitl wrapped in thick cloth to keep the obsidian teeth from cutting her. It was a habit learned from long months on the run.

She’d come south searching for survivors. The Mexica Empire had been vast, surely others had fled the ruined city of Tenochtitlan. There had to be some resistance, somewhere. She’d imagined the far south would be free of the Invaders’ influence. Now, she realized how foolish it was to believe she could escape them.

The sea was everywhere.

She crashed through a canopy of wet leaves to splash into the stream at the bottom of the defile. Choked with sticks and rotted foliage, the water was little more than a filthy trickle, the muck black as the inside of a tomb. She came up spluttering, clawing thick river mud from her eyes and nose. The mire was waist deep, a wild tangle of ceiba tree roots the only solid ground.

She waded toward the trees, grunting with the effort of each sucking step. After what seemed an eternity, she dragged herself up onto the ceiba roots and set about checking for broken bones. Apart from a tender patch on her ribs it seemed she’d escaped the fall with little more than scrapes and bruises. She’d kept her axe and macuahuitl, although the latter rattled as she unslung it.

The wild thrum of her heart had just begun to subside when Hummingbird heard the crash of falling trees from above. She glanced up, cursing as she saw branches shudder.

The creature crawled down the cliff as easily as if it were flat ground.

A quick look around told her the stream was too congested to swim. At the realization there was no way out, a strange calmness settled like a stone on herchest. It was fitting that she would die beneath a stand of ceiba. They were reflections of the great World Tree, its roots sunk deep into the Underworld, its branches spanning the heavens and beyond.

Slowly, almost reverently, she drew her bronze axe–taken from a Tarascan temple guard in the mad scramble of months after the fall of Tenochtitlan. She unwrapped her macuahuitl, the last vestige of her time in the Cuachicqueh, the most feared warrior order of the Mexica Empire. The saw-toothed club was missing a half-dozen blades and many of those that remained were chipped and cracked, but the bindings were still tight.

The air above her bent as the creature tore its way down the cliff, sunlight rippling around it as if refracted through water.

She watched it come, her jaw tight and her eyes slitted so the mad jumble of limbs wouldn’t disorient her. She’d thought she would be more afraid at the end, but all that bubbled through the cracks in her resolve was an odd sort of relief.

Hummingbird hadn’t lived like a Cuachicqueh, at least she could die like one.

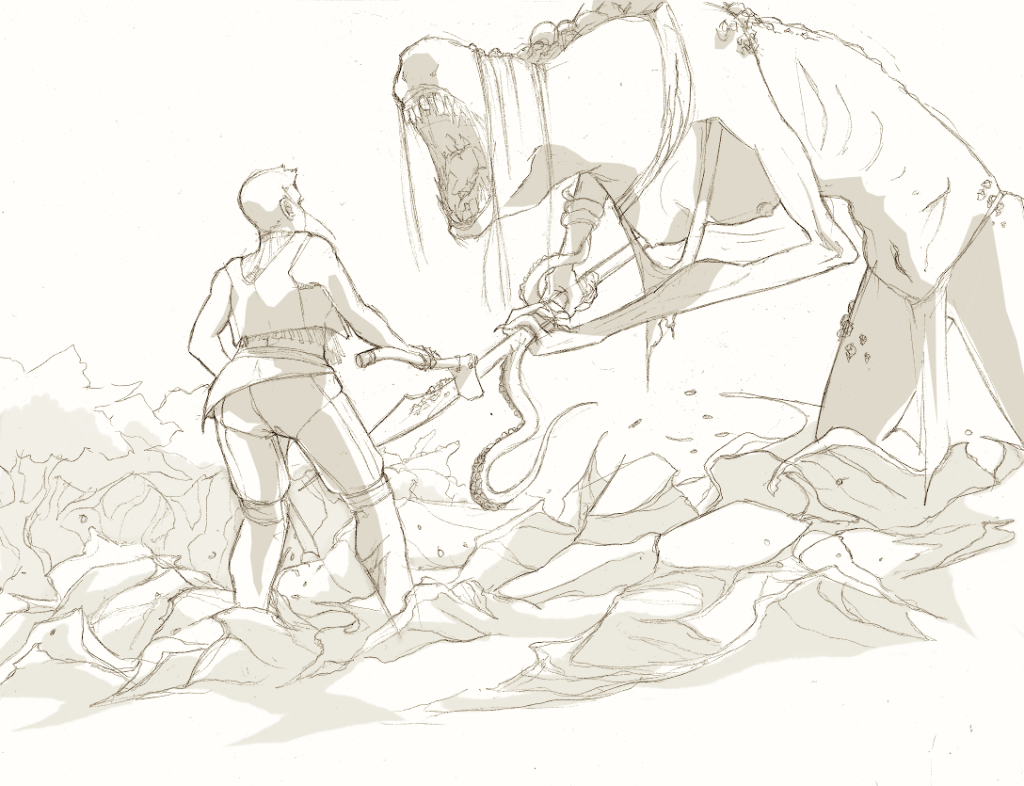

She charged as the thing crossed the stream, sawing her macuahuitl across one of its arms like she was cutting a joint of meat. Obsidian teeth lodged on cartilage and she tore the blade free then hacked down with her axe to cut the limb off.

The creature flailed at her with hook and talon, its jagged mouths stretched wide in a chorus of wet, gurgling shrieks. A claw tore the stitching from her quilted vest while a delicate, almost human looking hand caught her wrist, drawing her toward one of the thing’s wide, crocodilian mouths.

She ducked the swing of a barbed tentacle, then brought her macuahuitl around to carve into the arm holding her axe-hand. It released her, but instead of backing away, she pressed forward. This close, the creature could only bring a few of its arms to bear, and only at the risk of clawing itself. She drove her macuahuitl into the roof of the thing’s nearest mouth, then ripped it back in a spray of teeth and stinking blood.

Hummingbird caught a glimpse of wet fur through the tangle of limbs and snapping teeth. She swung her axe, only to trip over a ceiba root.

Bright lights flashed across Hummingbird’s eyes as her head rebounded from the hard wood, the edges of her vision curling up like a dry leaf. She tried to stand, but her legs were unresponsive, flesh prickling like she’d leapt into icy water.

The creature snatched her up and shook her like a dog with a rabbit in its jaws. There was a moment of queasy distortion as it pulled her close. Distantly, She heard her axe clatter to the wood, but she managed to keep hold of her macuahuitl. Blurred vision combined with the thing’s insane geometry to render the creature little more than a scribbled shape, the forest behind rippling like a thin sheet.

Strong jaws clamped onto her thigh, teeth pricking through the heavy quilted cotton. The spiky pressure was enough to make Hummingbird scream. She threw her head back, dappled sunlight filling her vision and making her eyes burn, but Hummingbird didn’t look away. She called to Nanahuatzin, the fifth sun, weakest and most humble of the gods, who had sacrificed himself on the pyre so that the world might have light and life. She knew better than to pray for aid or salvation, the gods of the Mexica were many things, but forgiving was not among them. It didn’t matter–Hummingbird didn’t want mercy.

She wanted revenge.

Slick, boneless limbs wrapped about her arms, her legs, her throat, the creature’s mouths shredding her quilted armor. A heartbeat, maybe two and its teeth would rend flesh, and still, Hummingbird didn’t look away.

A man stood silhouetted against the golden glare. Tall and broad-shouldered, he wore long breeches, his mane of long, wild hair fringed with feathers. A hatchet hung from his belt, one of the invaders’ matchlocks strapped across his back, the green jade ancestor figures on his necklace glowing like miniature suns. His chest seemed strange, the outline of rib bones just barely visible against the glare. She couldn’t make out the man’s features, but as he turned she saw in profile a face strong and sharp as if chipped from obsidian.

And she knew him.

“Lord.” The word was barely a whisper, lost amidst the creature’s mad shrieks. It seemed fitting that Emperor Moctecuzoma would come to collect the soul of one who betrayed him. Hummingbird wanted to call out to her lord, to tell him of the Sea People she’d slain, the creatures she’d fought, the temples she’d cast to ruin, how her life had cost the invaders more than her death ever would. Instead, she turned away, shame cutting deeper than the creature’s claws.

Moctecuzoma’s call was high like shriek of a jaguar. He was chanting, the words strange to Hummingbird’s ears–but incantations always were. There was a crack like splitting wood and the creature gave a shuddering howl, its grip relaxing. When she looked back Moctecuzoma had his musket raised, firing again. It seemed strange he would use the invaders’ weapons, even stranger that he would aid her.

The shot streaked toward the creature like a falling star, flashing by so close Hummingbird could feel the heat of it on her cheeks. The musket ball burned deep into the writhing mass. Moctecuzoma’s call became louder, more insistent, and the air seemed to fold around the creature, its outline turning hazy and insubstantial as a waking dream. She could almost see through it now, its grip weak as dry grass. She kicked free of the entangling limbs, stumbling a few paces before turning to swing her macuahuitl in a vicious slice.

Her blade found nothing but empty air. The creature was gone, as was her lord; the only remnants of either a patch of dark blood on tangled roots.

With a tired grin she tottered over to her axe and picked it up, feeling as if she’d downed a jug of pulque. It was all she could do to stand still, pressing one hand to a ceiba trunk to steady her blurry vision.

“Drop your weapons.” The speaker’s Nahuatl was thick and guttural, as if he spoke through a mouthful of mud.

Hummingbird turned to see four Sea People on the cliff above her, their muskets braced and leveled. They were fish belly pale, with wide, dark eyes and lank hair the color of rotting seaweed. Their wide, almost chinless mouths hung open as they panted, exhausted from the chase, revealing jagged teeth like a deep sea predator. The invaders’ weapons were sleek and long, less blocky than the matchlocks Cortés and his murderous conquistadors had used to great effect on the Mexica.

The invader started to repeat his command, then glanced at the bloody roots, and, unaccountably, began to laugh.

Hummingbird gauged the distance between them–ten, maybe fifteen paces up a sharp incline–a suicidal proposition even if she’d been at full strength. Still, it would be a quicker death than if she was captured. She raised her macuahuitl, drawing in breath for a death scream. Rough hands grabbed her arms, twisting the weapon down and away. She turned to see three other Sea People, boots discarded so they could slip barefoot across the roots. Clear-headed, she would’ve heard then coming half-a-forest away, but battered as she was, they’d managed to creep up on her.

Hummingbird stamped on the instep of the woman who held her, then twisted to elbow her in the throat.

A spear shaft cracked across her lips and she tasted blood.

“Stop, don’t hurt her!” It was the man who’d told her to drop her weapons. He was picking his way down the cliff, waving his arms.

Two more Sea People leapt on top of her. One pinned her legs, the other snaked an arm tight around her throat. The world seemed to draw back as if Hummingbird were falling down a long, dark pit. Every struggle came slower, harder–like she was fighting through thick mud. Her vision narrowed, the pit growing deeper. Dimly, she felt someone jerk her arms back, while another slipped a sack over her head.

Then she hit bottom.

#

Smoke, distant light, the air thick with smells of salt and rotting fish.

Hummingbird sat up, and immediately regretted it as her head began to throb. She tried to bring a hand to her forehead and found her wrists bound. Someone had seen to her wounds, linen wrapped over a thick, green paste that reeked of seaweed. She lay on a cot in a small, windowless chamber, the walls of mud-brick, the floor pounded dirt set with stones.

She shifted, squinting into the shadows. What little light there was came from cracks in the wooden door on the far side of the room. The glow was soft and irregular–fire rather than sunlight, but Hummingbird could just make out a table, chair, and–

“Are you awake?” The voice was familiar.

Hummingbird tested the straps on her wrists and found them tight.

“I’ll take that as a yes.” A taper flared, illuminating the sallow, dark-eyed face of the man who’d ordered Hummingbird taken alive. He sported a thick, dark beard, his short hair parted to one side in the manner of the Sea People. The candlelight lent his skin a sickly, almost jaundiced hue, flesh glistening like an eel or deep cave fish. He’d traded his breastplate and helmet for tight pants and an overlarge shirt of deep purple fabric slashed with gold. “You’ve been in and out for the better part of two days–fever, my healers tell me, probably from your battle with Crawling Thing. I can’t tell you how grateful I am you banished it. Working under the supervision of Governor Pedrarias’ watchdog was problematic.”

Hummingbird glared at him, fingers brushing the linen bindings on her thigh. Her stomach tightened as she imagined the clammy hands of the Sea People’s sorcerers on her.

“They say you’ll make a full recovery.” He gave a sad smile, then spread his arms. “Welcome to Granada, such as it is.”

“Who are you? Why am I here?”

“By Dagon, she speaks!” The man stood with a little bow. “I am General Francisco Hernández de Cordoba, and you are my guest.”

Hummingbird eyed the ground between them. If that idiot took a step closer she might be able to catch him with a lunge. A quick twist and the leather bindings on her wrists would serve as a passable garrote.

“Can I get you something to eat, drink? Our stocks are low, but I had a meal prepared.” Hernández gestured at the platters and cups on the table. His smile faded as if he could sense her murderous thoughts. “Ah, to business, then. I need your help.”

Hummingbird snorted.

The General poured himself a cup of cloudy liquid, sipping it with obvious relish. “Balché–the natives brew it from honey and tree bark, although I’ve taken the liberty of adding a few spices of my own. Are you sure you don’t want a drink? It’s really quite good.”

Hummingbird swallowed against hollowness in her belly, narrowing her eyes.

“Suit yourself.” He set the glass down with a sigh.

She kicked up from the bed, arms raised to slip her bonds over Hernández’s throat.

There was a crack like thunder and a bright flare as something cut across Hummingbird’s cheek. Blinded, she stumbled as Hernández threw himself to the side.

When Hummingbird looked up Hernández held a strange musket in one hand. Far shorter than a matchlock, the weapon seemed to be made almost entirely of metal. It had a fat body and a curved handle that fit into the General’s palm. Smoke rose from the stubby barrel.

Hummingbird gathered herself for another lunge.

“I wouldn’t.” For the first time there was no amusement in Hernández’s voice. “My pistol has five more shots.” He fired at the ground at her feet, then thumbed the catch back again, pointing the weapon at her face. “Four, now.”

Hummingbird sat back down.

“You’ve already seen our long rifles–faster and more accurate than matchlocks, and with far greater range. Governor Pedrarias is at Ometepe as we speak, ostensibly to acquire more, many more.”

“Ometepe?”

Hernández’s grin returned. “An island in the great lake. Two mountains form some manner of ritual spot, a place where the barriers between worlds are worn thin. It’s old magic, deep magic.”

“How?”

Hernández leaned forward, dark eyes catching the candlelight. “What have you heard of the Destroyer?”

Hummingbird’s confusion must have shown, because the General sat with a small sigh. “There are things beyond our understanding, beings as far removed from gods as gods are from us. They swim through the outer dark like vast ocean predators, reality bending in their wake. For the most part, they are inscrutable, uncaring, less interested in our world than we might be in a mote of dust. Occasionally though, something catches their attention like a fly struggling on the surface of a still pond. Governor Pedrarias is just such a fly. Before traveling to Ometepe, he was a sorcerer of little note, an embarrassment to our order sent to die in the south, fodder for Incan necromancers. But at Ometepe, he stumbled upon a means to catch the Destroyer’s attention.”

Hummingbird wiped the blood from her cheek. “Why are you telling me this?”

“Isn’t it obvious?” Hernández shrugged. “You’ve made quite a name for yourself up north, Cuachique–burning our temples, killing our sorcerers, defacing our idols. I want you to help me do all that, here, now.”

Hummingbird’s laugh was long and loud. “What do I care if you kill one another? You’re all invaders.”

“Father Dagon is a god, and like all gods he cares for us in his way. Dagon’s dominion is the slow wear of water on stone. The world will drown, but over ages. The Destroyer is not so patient.”

“If Pedrarias is such a threat, why haven’t you dealt with him yourself?”

Hernández laughed. “My people are no less immune to infighting than yours. He buys the elders of our order off with weapons for their private wars. More, he has promised them new worlds, new peoples to bring to the fold. They think him a fool, a weakling. They do not see the danger. Already the Destroyer’s sickness spreads, already our world begins to burn.”

“What does it matter if we burn or drown? My world is already ashes. The time of the Fifth Sun has ended. The gods will make a new world. They’ve done it before.”

“Mexica.” Hernández massaged the back of his neck, sighing. “Why did you come south, Cuachique? Were you running or searching?”

A glare was Hummingbird’s only reply.

Hernández glanced back at the door as if someone might be listening. When he continued, it was in a small, serious voice. “I saw him, too.”

Hummingbird rocked back, feeling as if the breath had been sucked from her. She had come south to search for the remnants of the Mexica and found only ghosts. Perhaps there was nothing left. But if so, why had Moctecuzoma’s spirit aided her against the Crawling Thing? If she could but speak to him and her sisters once more, if she could just show them how hard she’d fought to avenge them. They might not forgive her cowardice, but they could understand it, at least.

“Who was that man to you?” Hernández asked.

“My lord.” The words slipped out through lips that felt wooden and numb.

“If you wish to find him again, you must go to Ometepe,” Hernández said. “I can get you onto the island, past the wards and watch-devils and into Pedrarias’ sanctum. I have allies, friends who will help. Your weapons are outside. Agree and they will be returned to you. Kill Pedrarias, find your lord. You will–”

A series of hollow booms drowned out the last of Hernández’s words. Distant but loud, they reverberated through Hummingbird’s chest like the beat of festival drums. She’d raided enough Sea People camps to recognize the sound of a powder store exploding.

The door to the chamber opened, a guard silhouetted against the firelight. “Chorotegas.”

Beyond the guard, Hummingbird glimpsed running shadows. Shouts and screams drifted on the wind, punctuated by the sharp cracks of muskets.

The General grinned, pushing up from his seat. He took two steps toward the door before seeming to remember Hummingbird was in the room. “I’m not your enemy, Cuachique.”

And with that, he was gone, the door slamming behind him.

Hummingbird smiled as she hopped over to the table, picked up the clay pitcher and, as quietly as she could, shattered it on the ground. It was easy to find a sharp-edged shard and saw through her bonds.

She stretched, wincing at the tightness of her thigh wound. The walls of the house were solid, as was the door, but it hadn’t been made to hold prisoners and the roof was little more than straw thatch. Hummingbird had only seen one guard outside–decent odds, even if she was still a bit battered.

The roof beams were low enough she could reach them. Her fingers caught the rough wood, and she pulled herself up, scowling as points of red bled through the bandages on her leg. There was no pain though, nor any of the heat she associated with infection. For all the contempt Hummingbird held for the Sea People, their healers knew their craft.

The thatch was thick but old. She pushed a hand then an arm through the rotted straw, clearing a space for her to climb out onto the roof. The far side of town was little more than a wall of oily black smoke, flames from the powder stores spreading like brilliant flood. Natives and Sea People struggled in the haze, little more than smudged shadows in the smoke. Of Hernández, there was no sign, but the guard she’d seen earlier was still outside. He crouched behind a half-empty water barrel, his musket discarded, a short sword clutched in one white-knuckled hand.

Hummingbird dropped on him feet first, careful to keep clear of his blade. The force of the impact sent the guard sprawling. Before he could gather his wits, she was on him, one hand pinning his sword arm, the other snatching the dagger from his belt. He opened his mouth as if to speak, but all that came out was a gurgling hiss as she drew the dagger across his throat.

Hummingbird bore down as the guard’s boots drummed a faltering staccato on the cobbles. She watched the man’s flat, black eyes widen as the realization took hold of him, as he saw the end. Lips moved over needle-sharp teeth, trying to form words, and, for a moment, he seemed almost human.

Doubt seized her like an evening chill, but Hummingbird shook it off. No matter what Hernández said the Sea People were the enemy, they would always be the enemy, the fact that they quarreled among themselves made no difference. The General was only trying to use her.

As Hernández had promised, a bundle containing Hummingbird’s axe and macuahuitl sat on a nearby bench. Strapping them on, she turned toward the confused struggle below. If the natives were resisting the Sea People, then Hummingbird might find allies amidst the smoke and flame. Maybe this was why Moctecuzoma had saved her.

Grinning, she loped towards the fight.

Shapes twisted in the fire-lit haze. If they wore the quilted doublets, boots, and curved helms of Sea people, they died. If they wore their hair long, with feathers and bits of shell, faces painted and tanned chests bare, she passed them by with a smile and a nod. Hummingbird relished the simplicity of it all. Here, there were no questions, only the brutal honesty of life and death.

Smoke stung Hummingbird’s eyes, dry heat scorching her throat with every breath, but there were faces in the flames–gods, ancestors, a crowd of unquiet dead, hard and flint-eyed, their smiles tight as they watched Hummingbird mete out vengeance upon the invaders.

She heard Hernández shouting in the murk, and stalked toward his voice.

A score of Sea People had formed a rough cordon across the road, pikes braced against the furious onrush of natives. Hernández stood beside a pair of riflewomen, shouting as they sited on a native chieftain in a feathered cloak.

Hummingbird’s hurled dagger glanced off the helm of the first riflewoman, spoiling her aim. The second spun, already shouting a warning.

Hummingbird sprinted up to her, batted the woman’s rifle aside, then slipped her macuahuitl up and into the fanged oval of her mouth. She released the blade to wrench the rifle from the guard’s grip, swinging it like a war club into the face of the other riflewoman.

Hernández turned, his expression shifting from surprise to something almost like relief.

Hummingbird drove the butt of her rifle into his stomach, then kicked him in the knee. Hissing at the pain in her thigh, Hummingbird swatted the sword from Hernández’s hand, then hammered the rifle butt into his face.

He didn’t get up.

Turning, she saw the Sea People had pressed forward, driving back the much more lightly equipped raiders. One of them thrust at the native chieftain, who parried the guard’s spear with his war club, smashing the man’s face with the backswing. The move bought him less than a heartbeat as two more Sea People stepped into the breach. Seeing the tide turn, the chieftain hurled himself into the massed ranks, shouting at his followers to retreat.

Wincing at the weakness in her leg, Hummingbird braced the rifle against her shoulder, sighted on the lead guard’s back, and fired. She was used to waiting a heartbeat or two for the slow match to ignite the powder, but the rifle kicked with the trigger pull, surprising Hummingbird and sending her shot wide. Still, the Sea People were packed so close together it was impossible to miss.

Her shot struck a guard to the right of her target. The man spun, painting his fellows in a spray of arterial blood. Confused, the others hesitated as they looked for the shooter.

The native chieftain met Hummingbird’s gaze over the press of battle. With a nod, he turned and sprinted back into the hazy chaos.

Dropping her rifle, Hummingbird retrieved her macuahuitl and knelt to grab Hernández by his collar. The General groaned, but made no attempt to escape as Hummingbird dragged him back into the smoky shadows. More Sea People came sprinting through the haze, but their focus was on the retreating raiders

Hummingbird glanced down at Hernández. She knew she should kill him, but the General might be of use. She would find out whether he’d lied about Pedrarias and Ometepe. Then she would decide what to do. But first, she needed to get him clear of Granada.

Her right leg almost collapsed as she lifted the General onto her shoulder. It was a struggle to limp uphill, but Hummingbird kept her head down and gritted her teeth, trusting in the smoky chaos to hide her.

She made for the fallen stockade, threading through patches of still-burning logs and out into the cool, damp night. It was surprising how quickly the firelight faded and the shouts blurred into a low, distant roar.

She settled for dragging Hernández. Speed was more important than stealth, at least while confusion reigned in Granada. The raiders had fled south, if Hummingbird could loop around and meet up with them before Hernández woke–

A low whistle made her freeze. She glanced up to see a half-dozen natives watching from the bushes, spears and javelins pointed at her. Hummingbird let Hernández and the rifle drop, then slowly raised her hands.

The native chieftain stepped from the shadows. He was a short man, sharp-chinned with high cheekbones accentuated by soot and smudged war paint. His eyes were hard, his hair wild beneath his battered headdress. He carried a shield and war club, one of Hernández’s new rifles strapped to his back. The man’s posture and bearing were such that, for a moment, she wondered if it had been he and not Moctecuzoma who aided her against the Crawling Thing. But the profile was all wrong–his nose was flatter, his lips fuller, his eyes more deeply-set.

“I’m with you,” Hummingbird said. She’d picked up a little K’iche in her time fighting alongside the Maya of Utatlán. When the man seemed not to understand, she repeated the words in her own tongue.

“You are Nahuat?” His dialect was strange, inflected with an accent Hummingbird couldn’t place.

“Mexica.”

He regarded her for a moment, then nodded. “Good. I hate the Nahuat.”

“Are you the Chorotegas?” Hummingbird asked, remembering what Hernández’s guard had called the raiders.

The man made an angry noise in the back of his throat, gesturing at Hernández with his club. “Their name for us. We are Mankeme.”

“I’m Hummingbird.”

“I’ve heard of you.” The Chieftain’s scowl cracked, surprise bleeding through. He seemed to catch himself, gaze flicking to his followers. “I am Diriangen. And you have the General.”

“My prisoner.”

As if in response to Hummingbird’s assertion, Hernández groaned, pushing to his knees. The General blinked as he looked from Diriangen to Hummingbird to the gathered Mankeme warriors. A few of the natives started forward, but Diriangen held up a hand, his voice deep as he barked out commands in his native tongue.

“Not exactly as we planned, but the end is the same.” Hernández stood like an old man after a long sleep, his grin made a bit lopsided by the swollen cheek Hummingbird had given him. “Pedrarias is moving more quickly than I thought, we don’t have much time.”

“As we planned? I never–” Hummingbird clenched her fists as she realized Hernández wasn’t speaking to her.

“I’ll send word to my people.” Diriangen gave a quick nod, then turned back to the assembled warriors, already shouting orders.

“I owe you my thanks, Cuachique.” Hernández began a bow, then winced, one hand pressed to his bruised stomach. “The garrison responded faster than I’d intended. Your aid was quite timely.”

“You used me.” Hummingbird thrust her chin at the Mankeme. “Just like you’re using them.”

“Did I? Am I?” Hernández pressed a hand to his heart, expression turning sober. “From where I stand it appears as if you rescued me.”

“Well, then.” Hummingbird took a step toward the General, drawing her axe. “If you’re my prisoner.”

A low hiss from the trees to her left caught her attention. She glanced over to see three Mankeme warriors watching them from the shadows, javelins pointed at her chest.

“I’m Pedrarias’ second-in-command. Only I know the passwards and incantations that will get us onto Ometepe,” Hernández said. “Kill me and you doom these people.”

“You lie.” The muscles in Hummingbird’s arm felt tight as overtaxed rope, but she slipped her axe back into the thong on her belt.

“Come and see.” Hernández gave the strange high-shouldered flinch the Sea People used to indicate ambivalence. “You can always kill me later.”

#

“It’s a trap,” Hummingbird muttered, squinting across the moonlit lake at the distant shadow of Ometepe. The mountainous island towered above the water, higher than the great ziggurat of Tenochtitlan, its twin peaks shrouded in dark clouds.

“Perhaps.” Diriangen glanced along the shoreline where his warriors sat next to their boats. Compared to Hernández’s constant chatter, the Mankeme chieftain led his followers with nods and glances, the type of easy communication that only came from years together. Once, Hummingbird had known what that was like, to move as one body, to charge, knowing your sisters were behind you, that they would fight for you, die for you, just as you would for them.

Except she hadn’t, had she?

“Pedrarias has to know we’re coming,” Hummingbird said. It had taken the better part of a week for the Mankeme war parties to gather, and another day to build the boats that would carry them across the lake. Diriangen claimed his warriors had cut off all communication between Granada and Ometepe, but she had learned to never underestimate The Sea People.

“He doesn’t.” Hernández was little more than a rough shape in the gloom, but Hummingbird could almost hear his grin. “Pedrarias is a middling sorcerer, at best. The power here isn’t his. Don’t you feel it Cuachique? Something comes.”

Hummingbird chewed her lip, thankful the night hid her unease. There was a sense of expectation in the air, a subtle wrongness that gave her the feeling she was being watched. “We should attack now, while darkness hides us from the defenders’ rifles.”

“Rifles are the least of our worries. The Destroyer’s wrongness already has begun to spread. There are nightmares on Ometepe; and, as everyone knows, nightmares are most active–” Hernández gestured at the moonlit shadows. “–at night.”

Hummingbird wanted to cut the smile off the General’s face. Instead, she turned and stalked off into the woods. It had been like this for days–Hernández seemed to take perverse pleasure in argument, even when he was clearly wrong. She would’ve been able to bear his arrogance if the General’s words didn’t carry such weight with Chief Diriangen.

She walked until her progress was blocked by a stand of vine-covered trees. Instead of going around, she drew her macuahuitl and hacked at the vines, pretending they were Hernández’s scrawny arms, her hands sticky not with sap but the General’s blood. Unfortunately, like the Sea People, there were just too many vines, and, at last, she was forced to sit back, blood pounding in her ears, her breath loud in the dappled gloom.

“You shouldn’t have done that.” Diriangen stepped from the shadows to her left.

“They’re only vines.” Hummingbird scowled at him. There were a thousand jungle tribes, each with their own eccentricities and superstitions. She cared nothing for whatever Mankeme taboo forbade cutting weeds.

“These are ceiba trees.” The Mankeme Chief brushed aside the loose vines to run a hand over the weeping slashes she’d left in the trunk.

Hummingbird stood to regard the trees, running her tongue over her teeth. She hadn’t noticed before, but they were ceiba, although not of the thorny type she was used to in the north.

Murmuring prayers of apology, she drew one of her macuahuitl sharp obsidian teeth across the back of her foream, then smeared her blood across the wounds she’d left in the tree.

The act seemed to mollify Diriangen, who stood back, a rare smile ghosting across his lips. “He speaks of you as a friend.”

“Hernández?” Hummingbird turned, surprised.

“I thought it odd, as well.” The Chief’s grin held none of the grating arrogance of General Hernández’s. It smoothed the worry lines around his eyes, the hard set of his jaw, and, with a start, Hummingbird realized how young he actually was. “I didn’t want to bring you, but he insisted you could be trusted.”

“Me, trusted?” It was a few moments before Hummingbird could find the words. “Hernández lies as easily as he breathes. The Sea People are cruel and callous, a dark tide that devours villages, and tribes, and kingdoms. Their priests are mad sorcerers, their gods distant, hungry things that care for nothing but blood and sacrifice.”

The chieftain clucked his tongue. “You might just as easily be describing the Mexica.”

“You won’t have to worry about me.” Hummingbird glared at him. That Diriangen thought her people comparable to the invaders was only more proof of how deeply Hernández had ensnared him. “Once this is over, one way or another I’ll be gone.”

“Peace, Cuachique.” The chief waved a hand in front of his face as if dispelling a bad odor. “I have enough enemies, already. I didn’t come to make more.”

“Why did you come, then?”

The Chief glanced back toward the lake, his expression strange. Away from the eyes of his people the Mankeme chieftain seemed smaller, less sure. “Do you wish you’d died with them?”

“Who?”

“Your people.” He scratched the back of his head, not meeting her gaze.

They stood for a long time, the high whine of jungle insects seeming only to call attention to the silence.

“I don’t trust Hernández,” Diriangen said, at last. He seemed to deflate, his shoulders sagging, his expression turning pained. “But I can’t see another way to fight the invaders. I burn their towns, I kill their warriors, I smash their temples, but there are always more. And now, these weapons, this Destroyer. The sickness spreads, animals are not as they were, fish, trees–all have started to change, becoming monstrous. How long until my people follow?”

In that moment, Hummingbird knew him. She recognized the bitterness that lined his lips, the festering loss that hollowed his eyes. The Mankeme faced a terrible choice, to die a slow death or leap upon their own pyre.

Hummingbird scratched at the line of old scars on her cheek, then stepped close to lay a hand on Diriangen’s arm. “Almost every day.”

“What?” He turned, eyes catching the moonlight, his face close enough Hummingbird could feel the whisper of his breath on her cheek.

“My people. I regret not….” She frowned, still not able to say it.

Diriangen glanced at her hand, but didn’t pull away. Stripped of its customary frown, his features smoothed out, the worry lines around his eyes and on his forehead falling away to reveal a face that was striking, even handsome.

Hummingbird found herself suddenly aware of the play of his muscles under her hand, the warmth of his skin. Her sisters had always joked about how one could predict a battle by watching the brothels. The more desperate the conflict, the more warriors sought the comforts of the flesh, as if a few moments of sweaty fumbling could dispel their fear. The Cuachique had teased one another about this or that bed-boy, but the jokes had never bothered Hummingbird.

There were worse ways to spend a night.

“Better to die fighting.” She spoke softly, leaning forward so her lips were almost touching his, a bright point of heat spreading behind her ribs. “But if you have to live…”

Rather than reply, Diriangen reached for her, his kiss at first tentative, but gaining confidence as she let her hands play over his body. She’d expected him to be forward, to try and control her like he commanded his warriors–that, or to be awkward and overeager, flush with the inexperience of youth.

Fortunately, the Mankeme chieftain surprised her, again.

#

Bright points of light bloomed on the shore, the distant pops of rifles marring the early morning stillness. A score of war canoes hissed through the water, propelled by the powerful strokes of Mankeme warriors.

Sprays of cold lake water stippled Hummingbird’s face, refreshing after the long, humid night. Red-gold sunlight limned Ometepe, boiling away clouds and mist as if Nanahuatzin himself urged them on. They made it almost halfway across the lake before the guards on the island started firing. There was a moment of indrawn breath, nervous expectation sharp as the pause between injury and pain, then a woman to her left toppled into the water, disappearing beneath the green-black waves quick as a stone.

More followed, some collapsing as they were hit, others gritting their teeth and rowing all the harder.

Hummingbird turned to Hernández, but the General’s expression snatched the words from her. Hernández was staring at the water near the rightmost canoe, his eyes wide and his lips pressed into a tight, nervous line. Following his gaze, she saw nothing but waves stirred by an easterly breeze. It took a heartbeat or two to pick the disturbance out amidst the whitecaps–a line of waves, curved like the crest of a bow line, only there was no ship.

There wasn’t even time to cry out.

The rightmost canoe disappeared, dragged beneath the water quickly as a crocodile snatching a pelican. A few of its crew bobbed to the surface, their heads visible above the waves for less than a heartbeat before they too vanished. The canoes faltered as rowers craned their heads, searching for whatever lurked below the water.

“Faster! Faster!” Hernández grabbed up a loose paddle.

“You’ll throw off the rhythm.” Hummingbird pushed him back.

“I should’ve known.” The General’s laugh was high and panicked. “Below the waves it’s always dark.”

“Can you stop it?”

“I’m trying.” Hernández muttered under his breath, words and incantations that slipped through the air like smoke.

Hummingbird glanced toward shore–closer, now, but would it be close enough?

Diriangen urged his warriors on, arms raised like a priest preparing for sacrifice. Slowly, the rowers found their rhythm again, heads forward, jaws set in grim determination. The Mankeme had weapons of their own–a few rifles, but mostly matchlocks and bows. Some returned fire, while others shot at the water where the canoe had disappeared.

Whatever spell the General had cast must have taken hold, because no more canoes disappeared.

Hummingbird kept her head down. Shoulder to shoulder with Hernández, she waited in the bow, axe and macuahuitl bared and a chant on her lips. The canoe grated on sand, Hummingbird leaping onto the shore with a shrill war cry. Javelins hissed through the air above her, hurled by Mankeme warriors as they streamed onto the beach. Bright sparks marked where flint spearheads struck steel plate or helms, and sprays of blood where they found softer targets. Hummingbird sprinted up the beach, feet twisting on the loose soil. Some of the Sea People drew blades or reversed their rifles, others snatched up spears.

Hummingbird feinted at a swordsman’s head, dropping low as she slipped under his parry to drag her macuahuitl across his knee. He toppled, screaming, and she finished him with a quick chop to the neck.

Two more came on, their curved swords bright in the morning light. Hummingbird threw herself back, barely avoiding their wild swings. She tried to bat their swords aside in hopes of getting within the arcs of their blades, but had to duck back as a tall spearwoman joined the fray, stabbing over the heads of her companions. If they’d been on equal footing, Hummingbird could’ve moved to put the three in each other’s way, but fighting uphill and into the glare of the sun it was all she could do to keep the blades at bay.

Glancing back, Hummingbird saw dead and dying on both sides. Terrain and glare had conspired to blunt the fierceness of the Mankeme’s charge. More warriors streamed up the beach, but too slow, the canoes having hit the island in a staggered formation rather than a single line. Diriangen stood in the surf, gesturing with his war club as he urged his people on.

One of the Sea People caught Hummingbird’s macuahuitl with his blade, twisting the sword to drag her weapon down. She brought her axe around in a tight arc, only to feel it slide down the other invader’s blade as he stepped in to parry. The spear flashed in, quick as a diving osprey, and Hummingbird tensed her belly against the expected cold burn of steel.

But the pain never came.

The woman’s face crumpled as bullet tore through, blood painting the armor of her companions. Hummingbird wasted no time as the woman fell back, aiming a kick at the swordsman who pinned her macuahuitl. His scream became a wet gurgle as she sawed the blade across his throat.

Hernández shoved the other swordsman back, then calmly shot him in the stomach. He turned to her, beard dripping with blood.

For the first time, Hummingbird didn’t want to bury her axe in his smile.

#

If Hummingbird had any doubts about the threat posed by the Destroyer, the mountain put them to rest. Ometepe’s animals had become strange, monstrous things, twisted as if by some terrible hand. Flocks of bat-winged hummingbirds flitted around the war party, darting in to stab at the warriors with beaks barbed like fishing harpoons. If they were not crushed quickly enough, they burrowed inside the body. Many Mankeme fell shrieking down the hill, digging at their own flesh with knives and axes.

Clawed hands reached down from the tangled foliage above to pluck the heads from passing warriors. Diriangen would’ve been among them had not Hernández dragged him back at the last moment. Hummingbird joined the Mankeme in flinging javelins into the trees. What fell resembled sloths, but grown large and bloated. Their arms were thin, boneless things, little more than ropes of muscle with claws sharp as knapped flint. A warrior buried her axe in one of the things, only to have the creature burst like an overripe fruit to disgorge a swarm of fleshy mosquitos.

“I thought you said you could deal with Pedrarias’ devils.” Hummingbird shouted at Hernández as they ran from the cloud of biting insects.

“What makes you think I’m not?” The General slapped a mosquito. The insect popped with surprisingly human scream, leaving a smear of black blood on Hernández’s neck.

“We have seen similar things in the jungle around the lake.” Diriangen jogged up.

“This is but the wind of its coming.” Hernández glanced at the darkening sky. The clouds had taken on a pale green hue, shifting in strange patterns that tugged at the eye. “It will become far worse if the Destroyer enters our world.”

“How long?” Diriangen asked.

Hernández’s wince was all the answer they needed.

Farther up the mountain even the earth began to change, soil becoming slick and stone almost soft to the touch, its surface grainy like woven hair. The foliage became swollen, limbs straining under the weight of leaves grown fat and fleshy.

Only the ceiba trees seemed unaffected, although they hummed softly. Hummingbird paused to regard them, her palm pressed to a trunk, its deep thrum like the rumbles that presaged an earthquake or eruption.

“Don’t touch the–!” Hernández’s voice dropped away as Hummingbird’s vision blurred.

She smelled incense, blood, stone, the ceiba’s vibrations like distant thunder. She could see now that the tree was not one, but many, thousands upon thousands of trunks twisted together, their branches threading the sky, their roots sunk deep within the mountain. There was a shadow at the center, a place where the bark seemed almost to eddy, wood peeling back as a tanned arm reached up from within to grasp one of the knots and pull its owner higher.

Hummingbird drew in breath to call her lord’s name, but saw the man was not Moctecuzoma. He was brown-skinned and lithely muscled. His dark hair was wild as a temple priest’s, his unkempt beard the dull red of worn adobe. He wore a robe festooned with bits of tarnished armor, a rusty Sea People blade thrust through his rope belt.

Hummingbird expected the man to leap from the tree, but he only climbed higher, pausing to regard her with an expression that seemed almost embarrassed. With a grin, he held up a squat black pot. “Its heart is its eye.”

The words were not in Nauhautl, K’iche, or even the rough gulping tongue of the Sea People, and still, through some strange quality of the ceiba, Hummingbird understood.

Rough hands grabbed Hummingbird’s arms, dragging her back. Blurred shapes resolved into Hernández and Diriangen, their faces creased in almost identical expressions of concern. Hummingbird would’ve laughed if she’d had the breath to do so.

“What–?” she choked out between wheezing gasps.

“You went elsewhere.” Diriangen said. “Where it is.”

“That was stupid. You’re lucky you weren’t seen.” Hernández scowled at the nearby ceiba.

Diriangen helped Hummingbird to her feet.

“I’m fine.” She nodded at him. “A moment to catch my breath.”

“Did you see anything?” Hernández asked.

Hummingbird frowned. “No, nothing.”

The General gave her a searching look, then moved off to cut brush with the others.

Hummingbird glanced at Diriangen. “There was a man, dressed as a Sea Person, but not a Sea Person. He spoke of the Destroyer.”

“What did he say?” The Mankeme Chieftain’s eyes were like chips of obsidian in the deepening shadows.

Hummingbird frowned. “I’m not sure.”

Their progress up the mountain was maddeningly slow. Ometepe’s foliage was slick with mucus, vines and branches so limp it was like trying to cut hanging rope. Soon, they were all spattered with strange excretions. Warriors fell, exhausted or succumbing to earlier wounds. With each death Diriangen grew more grim, until his scowl seemed etched from stone. Hummingbird understood the weight, it was the same she had seen on her lord’s shoulders when the deeps had come for Tenochtitlan.

After what seemed an eternity, Hernández paused.

“Just through these cliffs.” He pointed his saber at a narrow defile cutting between sharp cliffs, the rock pale and glistening like the flesh of some deep sea fish. “The ritual space exists beyond worlds–there will be nightmares. I will do what I can, but Pedrarias has become a conduit for the Destroyer.” He glanced at Hummingbird and Diriangen in turn. “Someone must reach him.”

They took a moment to check their weapons, to tighten straps and hastily bind wounds. Then, shoulders tight with purpose, they marched into the defile.

There was a moment of queasy separation. The sense of wrongness intensified, sinking into Hummingbird’s chest.

A moment later, the screams started.

Hummingbird ducked a flailing tentacle, a shadow more sensed than seen. It caught the Mankeme warrior beside her, passing through him like a blade through smoke. His gurgling shriek dissolved into a sound like sizzling fat as he crumbled away to nothing. There were Crawling Things in the dark–their limbs little more than blurs, their bodies insubstantial as shadow.

Hummingbird looked around for her lord, seeking his golden light, but Moctecuzoma was nowhere to be found.

“Iä Dagon! Iä Hydra!” Hernández’s call rose above the din. The General stood still, arms spread and head thrown back as he chanted words that filled Hummingbird’s thoughts with images of cold, dark places where strange things dwelt, vast and ancient beyond all human reckoning.

A sea wind lashed the nightmares, its touch turning smoke to flesh. There was light now, although weak as the sun filtered through storm clouds.

“I can’t hold them for long,” Hernández shouted. His face had already taken on a greenish cast, shadows deepening his eyes and cheeks. He looked like a man at the point of death.

Gritting her teeth, Hummingbird buried her axe in the nightmare’s rubbery flesh, pulling herself up so she could hack down with her macuahuitl. In a heartbeat, Diriangen and his warriors were beside her, voices raised in their own high chant. Some pinned the Crawling Thing with spears, others leaping in to chop at it with axes and stolen swords. More nightmares came, and the Mankeme fought on.

Hummingbird dodged through the gap, but there was no direction, no ground, only an uneasy solidness beneath her feet as if she ran upon a bridge of floating logs. The air was hot, close, and humid in a way that made Hummingbird feel as if she were inside something. She spun away from snapping jaws, slapping aside a tangle of questing fingers with the flat of her axe. Something coiled around her leg then went limp as Diriangen severed it with a sweep of his flint axe. He set a hand on her arm to steady her, and with a nod they were off again.

Shapes struggled in the gloom, not just Mankeme but men and women in strange clothes wielding swords and rifles. Hernández had said this place was outside the world, that the Destroyer stretched across many lands, many times, perhaps others resisted as well.

“There!” Diriangen pointed with his axe. Amidst the chaos was the dark outline of a man. He seemed to notice them as they approached, and flung out a hand, threads of bloody muscle spiraling from the palm like jellyfish tendrils. Hummingbird shouldered Diriangen aside as the ropey mass hissed by. One of the threads caught her side, cutting through her quilted armor to flense the skin beneath. It was as if someone had buried hot coals in Hummingbird’s flesh, the pain reaching straight to her core. Diriangen dropped his axe to grab the strand of muscle, howling in agony as he tore it from her side.

He fell back, hands clutched to his chest, but Hummingbird’s pain dwindled to the manageable sting of a deep wound. She dragged Diriangen to his feet, then down again as another twisting net of muscle tore by.

“I can’t hold a weapon.” Diriangen’s voice trembled as he held out his hands, palms crisscrossed with angry red welts. “Go. I’ll distract him.”

Hummingbird drew in breath to protest, but the Mankeme chief was already up, shouting a war cry as he dodged around the sorcerer. Pedrarias swept the tangle of tendrils after him.

Hummingbird pushed to her feet, weapons held low as she sprinted for the sorcerer. She could hear it now, The Destroyer. It came like the beating of a thousand hearts, the wet slap of flesh on flesh, the snap of gnawing teeth. The sound seemed to echo from the sorcerer, as if Pedrarias’ body were a vast tunnel the thing was slowly squeezing itself through.

Shrieking the high battle-chant of the Cuachique, Hummingbird buried her macuahuitl in the swirling darkness that was Pedrarias’ chest.

The sorcerer barely flinched.

Pedrarias’ hand snaked up, fingers hooked, to claw burning furrows across Hummingbird’s chest. Her skin smoked and crackled at his touch, peeling, blackening. The smell of burning flesh filled her nose.

She bore down on the macuahuitl, willing it to saw through the shadow. A numbness spread from behind her eyes, pooling at the base of her skull. She could barely see, barely breathe, but still she pressed forward. She would carve out Pedrarias’ vile heart, raise it up as an offering to the gods.

Except his heart wasn’t his heart.

The ceiba man’s words came rushing back. Arms trembling from the strain, Hummingbird raised her axe and hammered the blade into Pedrarias’ eyes.

The darkness cloaking the sorcerer shattered like old pottery, shards of shadow falling away to reveal the small, frightened man beneath. Pedrarias was stick thin, his beard and patchy hair unkempt, his cheeks hollow, and his dark, pupiless eyes sunk deep in bruised sockets. Paler than even his Sea People brethren, the sorcerer’s skin had taken on a waxy, jaundiced tone, his forehead and arms slick with feverish sweat.

He stumbled back, hands raised as if to ward her blows. “Please, you don’t understand.”

Hummingbird raised her axe. “I understand enough.”

“The Destroyer is a bridge, a beginning, not an ending.” Pedrarias spread his fingers, dark eyes wide. “Through it, we can go anywhere, to any world. What is the loss of one sad, broken place compared to perfection? I’ve seen it, others have seen it. Do you think I’m the only sorcerer to call upon the Destroyer? This ritual is the work of a dozen worlds, a hundred, a thousand. Look and see.”

And Hummingbird did see.

They stood not upon a mountain, but a precipice overlooking a wild tangle of realities. The gods had made not one world, but a thousand. Hummingbird saw red earth pocked by tall fluted spires, strange cone-shaped beings with wide membranous wings fluttering in between; another world was built of stone and glass, squat buildings bright as mirrors reflecting a green sun; in still another man-sized beetles built domes that seemed to encompass the sky. Blinking, she shifted her gaze down, to worlds closer to her own. In some, the Sea People had been beaten back, in others they never were.

“Anywhere, anything. You have but to take a step,” Pedrarias said. “The way is open.”

Hummingbird saw her people, still proud, wise, and strong. She saw a world where Tenochtitlan stood untouched, where it gleamed.

She edged forward.

“Go on.” Pedrarias pushed to his knees. “Forget this world. It is doomed, anyway.”

A glitter of golden light caught her eye. Another world, close, but not too close. In it she saw her lord, dressed and armed as when he’d saved her from the Crawling Thing. He had his back to her, shouting at something or someone. Another man, pale as a Sea Person, stood a dozen paces away, rifle pointed at Moctecuzoma.

“Hurry, the way is closing,” Pedrarias said.

Already the worlds looked farther away, the tangle more like the branches of a tree than a skein of nested realities. Hummingbird glanced back at her perfect world. Her lord would be there, too, and her sisters. It would be as if she’d never run, never betrayed them, but to take that step, to abandon her world.

Hummingbird chewed her lip and spat. She was tired of running.

There was no way she could reach her lord in time to stop the man from firing, so she hurled her macuahuitl overhand, grunting with the effort.

It tumbled end over end, falling, spinning. She saw the rifleman’s eyes widen as the blade struck home in a spray of blood.

Her lord turned at the noise, and she finally saw his face–broad and deeply tanned, his cheekbones high, a determined cast to his jawline. What she’d thought were the bare rib bones of a spirit was actually a woven breastplate of beads and animal bones. Their gazes met over the shimmering distance, but although his eyes were the same warm brown as Moctecuzoma, the man was not Hummingbird’s lord.

She’d been mistaken. All of this was for nothing.

He glanced down at the man Hummingbird’s macuahuitl had hit, then back at her, confusion writ large across his face. A quick flutter and his world was lost again in the tangle of windswept branches. In a breath, they were all gone, but Hummingbird didn’t care.

She was Mexica, and like her gods she neither forgave nor forgot.

Shoulders squared, Hummingbird turned her back on the cliff. When Pedrarias lunged up from the ground, dagger in hand, her axe met him. This time, there was no monstrous shadow to blunt the force of her blow.

The sorcerer’s face made a very satisfying crunch.

Shadows lifted. They stumbled about the clearing like people woken from a fever dream, aimless and hollow-eyed. Sunlight trickled through the fleeing clouds, pale at first, but gaining strength as the Destroyer’s shadow retreated. Nothing remained of the battle but corpses. Pedrarias’ Crawling Things had boiled away to nothing, unlike the dead Mankeme. Of the hundreds of warriors Diriangen had brought to Ometepe only a few score remained.

Hummingbird saw the Chieftain walking among the corpses, his eyes red-rimmed, his lips pressed into a tight line.

Hummingbird felt like she should say something, but knew any reassurance would just be a lie. They’d beaten back the Destroyer, won the Mankeme a slow rather than quick death.

They found Hernández slumped against a boulder, arms limp, head lolling. He looked up as they approached, gaze crawling to the bloody axe in Hummingbird’s fist.

Diriangen looked at her, then nodded.

“Well, get on with it.” Hernández’s voice was little more than a dry croak. “We all knew this was coming.”

Hummingbird knelt next to the General. “I expected you to betray us.”

“What makes you think I haven’t?” Hernández’s smile was pained. He glanced at her bloody axe, and winced. “Where’s that shark-toothed club of yours?”

She glanced back at the cliff. “Gone.”

“Well, use my sword.” He nodded at the curved saber on the ground next to his feet. “I don’t fancy having my head hacked off.”

Hummingbird knelt to retrieve the blade, regarding the general for a long moment–sallow skinned, with the dark, bulging eyes and jagged predator’s teeth of his people. With Pedrarias gone, it was safe to assume Hernández would lay claim to whatever control the Sea People had over the south. And yet, Hummingbird couldn’t seem to find the strength to raise the saber. The general had kept his word, fought at their side.

Hernández closed his eyes, baring his throat. “It’ll be an honor to be killed by you.”

“Not today.” Hummingbird glanced back at Diriangen. “They’ll just send another–someone far worse. His death gains us nothing. ”

“Us?” The chieftain cocked his head. “Does that mean you’re staying?”

“For a little while, at least.” She stood, dusting off her knees. “Better to die fighting.”

Diriangen’s smile was a small, tentative thing. “Better to die with friends.”

“It’ll be an honor to kill you,” Hernández said, grinning. “Keep the sword. It wouldn’t be a fair fight, otherwise.”

Hummingbird’s glare was spoiled by her snort of laughter. From his sour expression, Diriangen hadn’t found the General quite as amusing. He looked to be reconsidering his decision to spare Hernández, but a shout from the far side of the clearing cut short any forthcoming pronouncements.

A small crowd of Mankeme had formed around the stand of tall ceiba near the cliff. They parted as Hummingbird and Diriangen trotted up, and she saw a score or more large crates stacked about the gnarled ceiba roots. The warriors had broken one open. Inside, Hummingbird saw the dark gleam of rifle barrels among the straw packing.

“There must be dozens.” Diriangen leaned over the edge of the crate, eyes widening as his warriors unloaded the contents. He took in the other crates. “Hundreds.”

“Enough for an army.” Hummingbird slapped him on the shoulder. “Enough to turn the tide, perhaps.”

Cries of surprise and delight echoed through the clearing as the Mankeme opened the other crates to find rifles, pistols, powder, shot, even a few small cannons. With a grin, Diriangen presented her with a pistol similar to the one Hernández used.

She took it, glancing to the sky, the sunlight bringing tears to her eyes. She’d thought turning her back on forgiveness, on perfection would rob her of hope, but it was the opposite. She’d seen other realities where the invaders could be defeated, were defeated. They were not invincible, they were not the sea, just some fish who had washed up on shore. It didn’t matter that her lord and her sisters weren’t here. Hummingbird knew they watched her. When the day came to face them, she would do it with head held high.

She turned back to the Mankeme. The future was murky as ever, their hope of victory faint as sunlight through water. Even with the new weapons it was likely to be a long, uphill battle. But none of that mattered.

Hummingbird had chosen this world. It was time she fought for it.

______________________________________________

By day, Evan Dicken studies old Japanese maps and crunched data for all manner of fascinating medical research at The Ohio State University. By night, he does neither of these things. His fiction has most recently appeared in: Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Apex Magazine, and Tales of the Sunrise Lands, and he has work forthcoming from publishers such as: Chaosium and Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores.