FOUND ON THE WATER

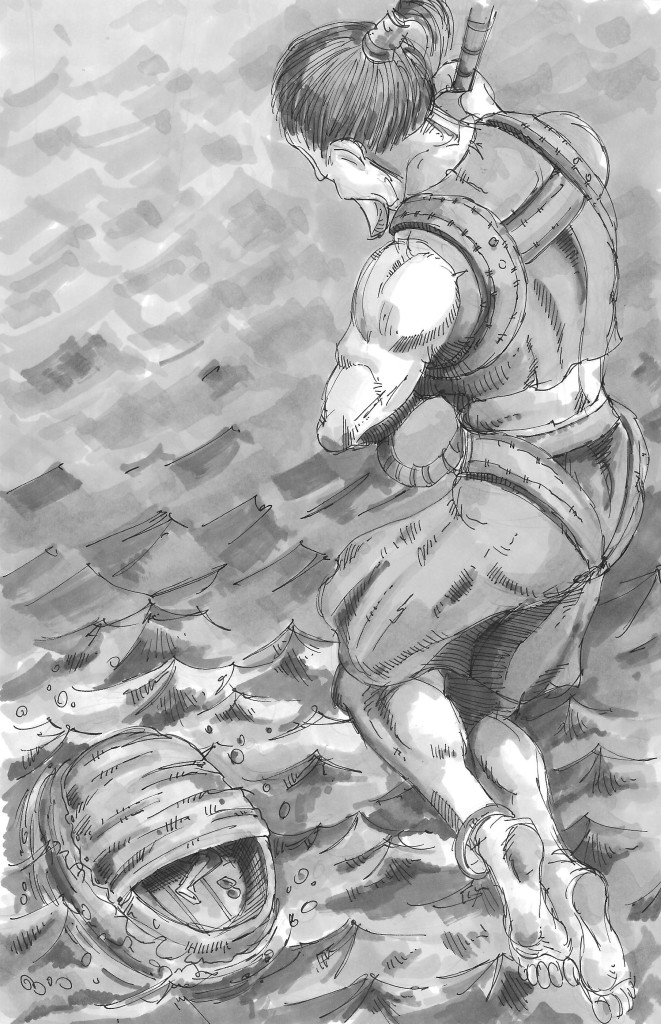

FOUND ON THE WATER, by Martha Wells (originally published at her Patreon), with artwork by Simon Walpole

The last thing Jai wanted to wake up to was Kiev leaning over her, saying, “We found something.”

She batted him away, squinting at the dawn light falling through the window slats. “What?”

“You need to come right away,” Kiev said, with dark emphasis.

Jai rolled out of her bunk in time to see Kiev disappear out the door. By the feel of the deck underfoot, she could tell they had stopped, which hadn’t been in the plan for this morning. Not that any of her plans for her wind-ship and crew ever came about exactly as she intended, but stopping in the middle of the sea for no reason wasn’t usually something they did.

Jai staggered around and pulled on the pants and the light sleeveless shirt she had discarded last night. It had been hard for her to wake up lately, probably because back home in Keres-gedin it was the darkest and coldest season. Some part of her brain had somehow never adjusted to the warm climate of the Ataran Sea. It didn’t seen to bother Kiev and Latal, but Latal was younger and Kiev was probably concealing any similar problem just to be annoying.

Jai stumbled down the corridor and up the ladder to the deck.

She was awake by the time she reached it, and the warm sun and salt-scented breeze cleared her head. They floated about a hundred paces above the surface of the shallow sea, which gleamed under the bright blue of the morning sky. Shiri must be in the steering cabin holding them in place, because both Kiev and Latal stood at the rail, looking down. Jai went to join them.

They were near enough to the great circular reefs that the shallow sea was even more shallow than usual. Jai could see the light-colored sand that formed the floor of the clear water, and the flicker of fish and other shelled creatures moving along it, the bright green of the water plants. For an instant she thought it was an odd rock somehow floating on the surface, caught by the dark ridge of a reef, but then her vision cleared and she realized it was a small boat.

It was gray and oddly round, more a boat for an island’s coast than for any long distance, but there were no settlements, either above or on or under the water, within sight. A cloth had been stretched over half of it, and she could clearly see something lay beneath it. She looked at Kiev and Latal, whose expressions were suitably grim. “Someone’s in it, and they haven’t moved,” Latal reported sadly.

“Ah.” Jai winced. They were looking at someone’s tragedy. One of the region’s rare storms or some other mishap must have taken the boat away from its island or reef, and the inhabitant had died of exposure. “We have to check, but there’s probably no hope.” Survival was unlikely, but barely possible, depending on the species of the occupant. Jai, Latal, and Kiev were kinet, and rare among all the different peoples who inhabited this region. They were meant for mountain ice and storm weather, with wiry dark hair, tall, heavy builds, dark brown skin that was thick and tough to deflect freezing wind, and short tusks curving down on either side of their noses. Fortunately these characteristics also made them resistant to the effects of heat and strong sun. Many of the inhabitants of the various archipelagoes were considerably more delicate.

“I don’t want to see it,” Kiev said with a shudder, and Latal shook her head rapidly.

“I know.” Jai was resigned. Neither wanted to see a person who had died of thirst and sun, which left it to Jai. Shiri, who was more practical, might volunteer to go but she saw no reason why he should have to see it, either. “If we ever turn pirate, you two are going to be useless. Shiri! I need the winch!”

***

After they got the winch ready, Jai buckled the harness around herself. They had lowered the Escarpment down to barely fifty paces above the water, which was as low as the ship could go. Wind-ships stayed aloft because they held a piece of flying island heart rock in the steering column. It allowed the little ships to fly along the invisible lines of force that crossed the Three Worlds, but it made them impossible to land.

Kiev had gone to take the wheel in the steering cabin and Shiri had come out to help Latal with the winch. Shiri was a native to the Ataran Sea, a water-surface dweller of the islands, and usually stuck with jobs as servants to other species. He was short and had gray-green skin and silver gray hair. He was young but had wrinkled and somewhat gnarled features that to other species made him look old and therefore wise. Jai would not go so far as to say wise, but he was an intelligent and able companion. He was on the crew because Jai liked him, and for him and Kiev it had been love at first sight.

Looking down at the little boat and grimacing in pity, Shiri said, “What are we going to do with…it?”

Burial customs were different among all the myriad peoples who traveled and lived in the Ataran Sea, and it would probably be impossible to figure out where the poor dead being had come from. “I’ll sink the boat,” Jai told him.

“Careful,” Shiri said, as Jai kicked off from the rail and the line took her weight. He worked the winch and watched her worriedly as she dropped toward the sea. “Don’t sink yourself.”

An ordinary wind-ship would have found this task difficult, but the Escarpment had been modified by Kiev to make use of ilene, a mineral from Keres-gedin that could be used to produce light and heat, and also to power things like winches and propellers. With careful maneuvering from above, Jai was able to drop down close enough to hook the boat with her heel, and then climbed down into it as Latal released the slack on the line.

It was a sturdy little boat, made of some thin resilient substance and reinforced with reedwood straps. The cloth shelter looked like it had once been a garment, and stretched across half the boat. Some scraps of palm frond and fish bones lay in the bottom, along with dirty stained rags and pieces of wood flotsam. The figure huddled beneath the shelter was half-wrapped up in light cloth, and all she could see of it was two curled up legs. The skin was bright gold, without scales or fur, and the feet not much different from Jai’s own. The smell was not as terrible as she would have expected, but then the light breeze must be carrying the death-stench away.

With an anticipatory wince, Jai edged closer and tugged down the cloth covering the head. It was the sort of face common to soft-skinned groundling species, as far as she could tell, past the dark hair sweat-plastered to the forehead. The gold skin across the chest was tight and the cheeks were sunken, the closed eyes deep in their sockets. She still didn’t recognize the species.

The same moment as Jai realized that this close she really should be able to smell death, the eyes opened.

Jai jerked back and swore. She turned to shout up to the ship, “Send water! And the other harness!”

“What?” Shiri yelled from above. “It’s alive?”

“No,” a thin voice croaked.

Jai twisted to face it. “What do you mean, ‘no?'” Then it occurred to her that being adrift in a small boat for some days might possibly cause one’s wits to fail, at least temporarily. “You need water. You may not think so–”

The figure heaved itself up on one arm and rasped, “I’m not mad. I can’t take water from you.” It spoke Kedaic, a common trade language throughout the Ataran Sea.

“We have plenty.” Jai waved urgently up at the Escarpment. She could see frantic moving about on deck. The jolt of motion inside the little boat had freed it from the reef’s shallows and the current had picked it up again. The Escarpment eased forward to stay above them, then Latal swung over the railing, wearing another harness and carrying the extra one and a waterskin over her shoulder. One of the benefits of wind-ships was the ample space for carrying supplies and water casks.

“I can’t take it!” The person apparently refusing to be rescued dragged the cloth off its head. It was male as far as Jai could tell, and dressed only in a ragged pair of pants. “I can’t take your water!”

Jai said firmly, “I am not going to argue with you!”

He shouted back, “I’m not going to argue with you!”

Latal dropped down in the other harness to stop a few paces above the boat. She held out the waterskin. “Why are you yelling?”

Jai snatched it. “This idiot refuses to understand that we are giving him water.”

The idiot dropped his head into his hands. “I won’t take your water.”

“Ask him why,” Latal suggested reasonably. She swung around on the harness to address the idiot directly. “Why won’t you take the water?”

He looked up at her. “I’m being tested.”

Jai stared, then exchanged a puzzled look with Latal. “Tested how? By who?” The horizon was empty as far as she could see, nothing but clear blue sea, the quiet interrupted only by waves lapping the reefs.

He shook his head. Latal said, “Are you being tested for how long you can go without water?” She tapped her own cheek. “Because unless your face is supposed to look like that, you aren’t doing so well.”

He lifted his hands in clear exasperation. “I’m still alive. It’s a…test of endurance.”

“Who is testing you?” Jai asked, with less patience than Latal.

“My family.” As he said it he glared up at them, as if daring them to comment on it.

Latal protested, “But there’s no one anywhere nearby.” She pointed up at the Escarpment. “The sea is empty in all directions, and you’re in a current, moving away from the nearest islands. How can–” She stopped as Jai nudged her.

Jai was beginning to understand, and it made her heart sink for him. He was younger than he looked. The tight skin and sunken patches in his flesh was from lack of food and water, not age. She said, “There are rules, in this test?”

He had expected her to dispute the test’s existence so this concession confused him. After a hesitation, he admitted, “No, I don’t know. I don’t think so.”

“You are allowed to drink rainwater, and condensation.” She pointed with one toe to the palm leaves in the bottom of the boat, which had probably been blown into the sea from some distant island and carried in the current. “And use whatever you can find on the water.”

After a moment, he nodded.

Jai shrugged. “We have fallen from the sky.”

“You’ve found us on the water,” Latal added, and tossed the waterskin into the boat, within his reach.

He stared down at it, then reached out a tentative hand. The material was fish skin and touching the cool dampness of it seemed to be too much for him. He pulled it toward him, fumbled the stopper out, and drank.

Latal turned her head toward Jai and mouthed the words “What now?”

Jai had no idea. Luring him up into the wind-ship seemed the next obvious step. She knew she was big enough to wrestle him up into it if necessary, unless he was far stronger than he looked, or had a weapon hidden away somewhere. But she didn’t want to do that unless it was absolutely necessary to save his life.

Partly it was because of a deep inner reluctance to make decisions for a stranger she knew nothing about. Jai didn’t want such high-handed decisions made for her and so didn’t care to make them for other people, no matter how odd she thought their behavior was. Part of it was the distant possibility that he might be right about the test, though if true it seemed a daft and cruel thing to do to anyone.

He lowered the waterskin, a sign that he still retained too many of his wits to drink until he was sick, and wiped his mouth. He said, “Thank you.”

His voice sounded less raw. Jai said, “And you need a little food. Perhaps you’ll come up to our ship and eat something.”

But the stubborn set to his face returned. “No. You should go now.” He held the waterskin out.

“No, you keep it. As I said, we have plenty.”

He stared at them, Jai eyeing him thoughtfully and Latal still dangling from the harness and watching him with open sympathy. He set the waterskin down carefully in the bottom of the boat but said again, “You should go now.”

“I’m in no hurry,” Jai said. “Latal, go up and tell Kiev and Shiri we’ll be here a while.”

Latal pulled the release on her harness and the deck winch groaned as she moved upward. Jai said, conversationally, “We’re heading toward Sidila Windward Port, but we have no reason for haste.” This was a lie. They had just dropped cargo off at Mirtracka Basins but there had been no opportunity there to pick up anything for transport. They were heading toward Sidila in the hope of getting in on the shell harvest shipping. But Jai had no intention of leaving this young person to die. “It’s pleasant to sit here and enjoy the sea.”

He hesitated, squinted up at the wind-ship, and seemed unable to decide what to do about this strange woman who had gotten into his boat and now refused to leave it. He finally said, “Do you all look like that?”

“Like what?” Jai stroked her tusks.

He looked away, the gold color in his cheeks darkening. “Sorry, I– I’ve never seen people like you before.”

“I’m teasing you, nothing to be sorry for. We’re kinet, from a very distant mountain city. You met Latal, and Kiev is currently steering the ship. Shiri is from the archipelagoes and would look more familiar to you.” Jai thought she had been forthcoming enough to elicit some information in return. “And what is your name?”

“I’m Flaren, from Issila.”

That explained some of it. Issila was a floating city some distance to the east. It engaged in commerce with the archipelagoes, but was somewhat isolationist in its dealings with them. “You are a sailor?” Jai asked. Surely his little boat hadn’t been driven all the way here from Issila. It would have taken days and days. “You fell off your ship, in this boat, perhaps?”

He glared. “Are you trying to be funny?”

“A little. You haven’t told me about this test. If there are no rules, how do you know when you win?”

He stared resolutely across the water. “It’s not a game. If I survive, I’ll prove myself.”

If true, it was a cruel piece of work. Being prodded out of the home to make your own living was nothing compared to it. And while Jai’s family home had not been the most loving, no one had ever been abandoned in a snowbound mountain pass to die. You couldn’t shout at dead people. “This is common in Issila?”

He blinked, and for an instant his voice was choked. “I didn’t think so.”

Jai stared at him. Oh, that’s almost worse. She tried to keep the sympathy out of her voice. He was very proud, and maybe still a little outside of his own mind because of the days of isolation and deprivation. She didn’t want him to stop answering her. “Who is testing you in this way?”

He hesitated, then said, “My father.”

The whir of the winch made both of them jump. It was Shiri, dropping rapidly down in a harness. He stopped himself neatly three paces above the water, then his line started to spin, whirling him around. Jai reached out and stopped him. “Yes?”

“Thanks,” Shiri said breathlessly. He glanced from Jai to Flaren. “Kiev was checking the maps. There’s a forest nearby and this current is taking you right into it.”

Jai swore under her breath and twisted around in the boat to look. “That way?” She could see nothing on the surface, but then that was to be expected.

Shiri swung around again and pointed. “We couldn’t see the trees from the deck, but there’s a shadow under the surface.”

“What is it?” Flaren asked. There was a trace of suspicion in his tone, as if he thought a menace might have been invented to trick him into leaving the boat for safety. Jai only wished she had thought of that.

“It’s an underwater forest, growing in one of the deep wells in the sea floor. Very pretty, but they often harbor voracious and angry wildlife.” The fact that Flaren hadn’t heard of it before told her he wasn’t widely traveled, at least in this quarter of the Ataran sea. “We’re usually not concerned with them, since our mode of transport is a wind-ship.”

Shiri said, “You shouldn’t risk it.” He twisted around to tell Flaren. “I understand you’re having a delusion or something but you need to snap out of it and come up to the ship before you get Jai killed.”

“No one is getting killed,” Jai said.

Maybe she shouldn’t have said it so forcefully.

Jai spotted the ripple even as Latal and Kiev screamed in chorus. Something just under the water moved rapidly toward them. She yelled “Go!” at Shiri, who hit the control to retract his harness. As he shot upward, Jai lunged across the boat, grabbed Flaren, and hit her own control.

Flaren, perhaps too confused, or too sensible to resist, grabbed her shoulders. Jai felt the tug of the harness and they lifted away from the boat. She had time to think that it was a close brush with death, but only a brush.

Then cool darkness dropped over her and something slapped her unconscious.

***

Jai lay in a very uncomfortable position and her head throbbed. Someone leaned over her, saying, “Are you all right? I’m sorry, I’m sorry.”

“Oh, did we hit the hull?” Jai managed to say. Her temple hurt where something had struck it. It had been just enough to knock her out of her senses. She thought their combined weight and flailing had caused the rope to swing, and the winch had brought them up under the ship instead of alongside it. Then she opened her eyes. She saw Flaren first, looking down at her with a guilty expression creasing his golden brow.

“Uh, no, not the hull,” Flaren said, with the air of someone reluctant to give bad news. “I think I hit you in the head with my elbow. Accidentally, I mean.”

Blinking, Jai realized the dim, strange quality of the light was not a head-injury-induced defect in her eyesight. Instead of the clear blue sky of the Ataran Sea, something filmy and grayish-white arched over them. The light glowing through it was still blue-tinted, but was dimmed and…

Jai sat up abruptly as Flaren fell back against the side of the boat. “Oh, fuck a mountain! It ate us?”

The water-forest dweller must have sensed their presence and left its deep-water well to hunt. Fast-moving in the shallows, it had come up beneath them and swallowed them into its belly. Jai had seen these creatures from above, some no larger than a merrow, and some big enough to eat the Escarpment. This one was bigger than that, surely. The Golden Islanders called them sea-flowers. They were pretty things from a distance, translucent and jelly-like, gleaming with pastel colors, with trailing tentacles like vines. They were not pretty from the inside.

“It did eat us,” Flaren admitted, trying to lever himself up. “I should have listened– It’s my fault–”

“It is, and you should feel terrible, and learn from your mistake.” Jai waved a hand at him. “But now you hush while I think.”

The fleshy chamber was awash, but the water wasn’t high enough to float the boat. What she could see of the surface they were aground on was thick and jelly-like, bluish with white patches. Perhaps one of the patches… She spotted a lump towards the middle of the space. It rose a pace or so above the floor, thick, slick and gleaming in the dim light. It was directly below the puckered circle in the center of the arching ceiling, which she assumed was the closed “mouth” of the sea-flower. It was too high to reach, even if she stood on Flaren’s head, but the lump below it had to be important. “There! That!”

Jai reached for her knife, and abruptly recalled she had thrown her clothes on when Kiev woke her and she hadn’t bothered with her belt with its handy tools or, indeed, her shoes. She still had her harness on but the rope had been severed by the sea-flower’s jaw. With a sinking sensation, she said, “Tell me you have a knife.”

Flaren had twisted around to stare at the lump. “A knife…” He turned back to the remnants of his little shelter, which had collapsed into the bottom of the boat. “You think that will help?”

“It won’t not help,” Jai said, distracted as she helped him dig through the mess. She found it first, a small piece of metal that looked as if it had started life as an armband and had been beaten into shape. It was not sharp. “This is it?”

Flaren nodded. “I made it.”

“We need something bigger.” Jai felt the edge of the boat’s hull. The material was stiff, and might work. The little knife was fine for cutting fish and seabirds but they needed something with more stabbing force.

She sawed at the edge of the hull, forcing the blade through the stiff material. It was some sort of tough plant substance, dried until stiff, with almost a metallic consistency. Flaren crawled over to help her by twisting and bending at the piece as she sawed at it. Jai felt sweat dampen her skin; the air was turning warm, but this was a big space, with plenty for two people to breathe. If they didn’t escape, suffocation wouldn’t take them before digestion did.

Jai shifted her weight so they could both put all their strength into pulling at the cut section. She said, “So you said your father constructed this test.”

Flaren didn’t reply, and Jai added, “I feel I am owed explanations.”

That did it. He said, “My brother accused me of plotting against my father. I did argue with him. I didn’t plot.”

“They set you adrift for arguing?” If such a practice had been common in Keres-Gedin where Jai had grown up, the city would have been empty.

“We believe in respect,” Flaren said, his voice rough with the effort.

Jai snorted involuntarily, but managed not to comment.

The piece snapped off abruptly and they both tumbled backward into the bottom of the boat. “Sorry,” Jai muttered as she elbowed Flaren in the gut while levering herself upright. She grabbed their makeshift spear and slung herself over the side.

Water splashed as she landed in the squishy substance. She grimaced and started to step toward the target lump, perhaps ten long paces away. She felt a prickling sensation in her bare feet and thought, oh, that was all I needed. Many sea creatures were poisonous to the touch and it was unsurprising that this one’s insides shared that annoying characteristic.

Flaren struggled out of the boat to follow her before she could warn him. But then perhaps it was better to be together when she–

The substance underfoot lurched and Jai swayed and staggered. Flaren stumbled forward and grabbed her. Four legs proved better than two and they stayed upright. He gasped, “We’re moving.”

“Indeed we are.” Jai plunged forward, dragging Flaren behind her. If the sea-flower moved out of this shallows into the deep water well of the forest and dropped, it would be too dark to find the lump. Groping around in the dark for it while the thing’s insides stung them to death was not a pleasant prospect.

Swaying and stumbling with the motion, the acidic burning sensation creeping over her feet to her ankles, Jai reached the lump. She lifted the spear and almost fell sideways; Flaren caught her from behind and hugged her waist to steady her, bracing his feet wide. “Good,” Jai told him. “Be ready. One – two – three!” She stabbed the spear down into the lump.

It pierced the sickly surface and drove deep. Still gripping the makeshift weapon, Jai waited, her eyes squeezed almost shut in anticipation.

Nothing happened.

Behind her, Flaren moaned, “Oh, no.”

Jai straightened up. She had thought they could get out of this. She had been so certain. The sickening sensation grew in her stomach. “If you have any thoughts on our next course of action, I would be happy to hear–”

Above them, the ridge around the closed mouth trembled. Then it splayed open and the surface underfoot contracted as the sea-flower turned itself inside out.

It happened so fast, Jai’s senses were too confused to understand. Then she felt the cool welcome sea breeze in her hair, and abruptly realized that meant she was falling rapidly through empty air. She had just the sense to take a deep breath and hold it, and curl her body up. At that point she struck the water.

She plunged deep, but the sea-flower must not have flung them very high, because the impact was not stunning. She flailed upward and broke through the surface to sun and wavelets and wonderful sweet air. The salt stung her injured feet but the water washed the poison away. She took a deep breath and looked for Flaren.

Hah, there! He floated some thirty paces away, face down. Jai swam toward him with all her strength, reached him and flipped him over. Treading water and hoping the sea-flower didn’t come back for another try, she fumbled for the right spot in Flaren’s alien bone structure and then squeezed his chest. He choked and coughed out water. She felt him shudder with returning life.

Then a rope harness slapped her in the head and she twisted to stare up at the welcome sight of the Escarpment‘s hull.

***

Jai lowered Flaren to the deck with Latal’s help, then stepped to the railing to see what Kiev was shouting about.

He pointed dramatically. “You were inside that thing!” he shouted, as if she had done it deliberately.

She could see the flower from here, a beautiful blue-streaked white shape, undulating gently as it pulled itself over the shallow sea bottom toward the darker water and the trailing fronds of the forest. It slid into the shadows and Jai made a rude gesture after it. “Kiev, Flaren will need more water and some food, please. Something soft to start with, that goes down easy.”

As Kiev hurried off, she went to Shiri, who had been keening the entire time he had worked the winch to draw them up and was still doing it. She took him gently by the face and said, “Shiri, we’re all well. Please stop.”

Shiri stopped, swallowed, and nodded. Jai let go of his face, stood patiently while he hugged her, then went to sit down across from Flaren.

Latal vigorously rubbed at his shoulders and head with a towel, and the deck was warm from the sun even though they were in the shade of the cabin awning. It was a better place for them both at the moment than a cooler cabin. Latal left Flaren with the towel and settled behind Jai with a fresh one, using it to press the water out of her braids. Latal had brought a jar of medicinal salve as well, and slathered it on the burned patches on Flaren’s skin. Jai pulled it over and took a dollop for her feet, still stinging a little from the sea-flower’s acid. Flaren gazed at her blearily, “I’m sorry,” he said again, his voice raspy from the saltwater.

Jai said, “I accept your sorry. Did you learn from your mistake?” With the grime washed away, his golden hair sticking up in all directions and gleaming in the sun, he was actually rather pretty, even for a different species. And he had followed her direction at a moment of extreme dismay and horror, always a plus.

“Yes.” He took a deep breath and coughed. “They weren’t coming back for me, were they.”

It wasn’t a question. Latal made a noise of sympathy. Jai said, “No, sweetling, they weren’t.”

Flaren nodded. He leaned back against the cabin wall, muscles starting to go slack with exhaustion. “I need to prove myself first.”

Jai blinked. “You need to what?”

Latal squeezed her shoulder, and switched from Kedaic to the old language of Keres-Gedin to say, “Not now. He’ll just want to jump off the ship.”

Jai let her words die in her throat. Latal was right. Flaren needed to time to rid himself of his delusion. “Sidila Windward Port might provide you with some way to prove your worth.” But as she said it, she realized she didn’t want to consign him to some other crew who might not understand his problem. “Or you could help us with the shell harvest.”

“I could do that.” Flaren stirred as if he expected to start immediately.

“We need to get to Sidila first,” Jai said, “and you need to recover.” By the time they reached Sidila, she would decide if she would send him on his way, or if she would invite him to join the crew.

Whichever, it was bound to be an interesting trip.

________________________________________

Martha Wells is a science fiction and fantasy writer, whose first novel was published in 1993. Her most recent series are The Books of the Raksura, for Night Shade Books, and The Murderbot Diaries, for Tor.com. She has also written short stories, media tie-ins for Star Wars and Stargate Atlantis, YA fantasies, and non-fiction. Her work has won the Hugo, Nebula, Locus, and Alex Awards, and appeared on the New York Times Bestseller List and the USA Today Bestseller List.

Simon Walpole has been drawing for as long as he can remember and is fortunate to spend his freetime working as an illustrator. He primarily use pencils, pens and markers and use a bit of digital for tweaking. As well as doing interior illustrations for various publishing formats he has also drawn a lot of maps for novels. his work can be found at his website HandDrawnHeroes.