THE SONG OF BLACK MOUNTAIN

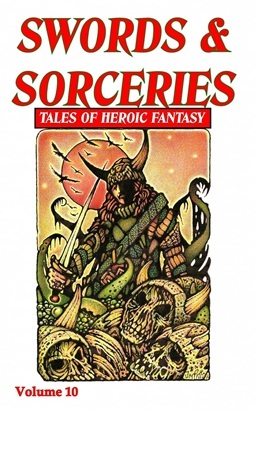

THE SONG OF BLACK MOUNTAIN, by Darrell Schweitzer, artwork by Gary McCluskey

I will make the song of the Black Mountain.

Hear how it begins:

It was because dragons still lingered above the peak of the Black Mountain that the King of Kings, Emperor of All the World Worth Ruling called together into his palace of marble and crystal and light all his knights and his priests and his prophets, in solemn conference. Yes, some hero had climbed that mountain once before and slain the sorcerer who dwelt there, and had driven away the sorcerer’s faithful dragons. That much is told truly and in a manner worthy of the glory of those deeds, elsewhere, in other song and story. But now reports came, from prophets who had dreamed them, and from those few bold adventurers or madmen who had ventured into the far land where the Black Mountain stood, to the effect that the dragons still circled, never settling to earth, but drifting and turning expectantly on the currents of the air, waiting. Every once in a while, if you looked up at the brilliant stars where the tip of the mountain touched them, a star blinked, eclipsed by a passing dragon.

It was clear that some evil remained. A further deed was required. Another hero must be called forth. Another quest must be declared. The blare of trumpets would announce it.

Yet before any quest was declared, a knight named Altheric set out. He was barely a knight, that is to say the son of squire who had done good service to the king once, and received as a reward the right to dub his eldest son a knight. No riches came with the title, nor any lands, but it was enough that Altheric was a knight. As such, the least of that company, he was permitted to stand in the back of the hall in his mismatched and dented (but lovingly polished) armor and listen while the Great King and his priests and prophets and the foremost of his warriors sat in conference, debating what was to be done.

And because he was standing in the back and of no particular importance, he was able to slip out unnoticed; and since no quest had yet been declared nor hero chosen, and the trumpets were as yet silent, he was able to set forth before anyone else did. For it was his intention the achieve the quest himself, before it even was a quest, and so present the Great King with whatever trophies he might gain to the amazement of the court, after which, he was sure, he would not lack for wealth or lands or glory.

A hero has to take the initiative, after all.

So it was that he rode on his poor horse, a shabby, stooped-backed mare that had once pulled a plow, not quite as swiftly as another knight might have, but he still had the advantage of a head start. He passed out of the familiar lands, and came to the shore of a raging river filled with monsters, and treated with a demon ferryman on its shore. In exchange for the horse, and a mouthful of his own blood, which the demon spat into the river, stilling the waters and calming the monsters, he was conveyed across. Then he made his way on foot into the country beyond, hacking through a forest of writhing thorn trees, then traversing a deadly desert, which could only be crossed at night, since by day the skies swarmed with birds of living flame – somewhat like the phoenix, only less benign, of no symbolic meaning, and never entirely consumed by their own fires. It took three nights to cross. Just before each dawn, he dug a hole in the sand, climbed in and covered himself with his shield.

Then he came to the Black Mountain, just before sunrise as it happened, and without taking any rest spent that whole day climbing a perilous slope like a jumble of obsidian as sharp as knives. It was only when he reached a ledge halfway up, that he allowed himself any pause. The stars were out by then. Far above, something screeched. One or two stars did indeed blink, as something passed before them.

#

Now this is all in the official version, to be told and sung and chanted, and it is heroic enough, if lacking in compassion for the horse, whose ending was no doubt terrible. But what it doesn’t mention is that Altheric brought his own minstrel along, me, Valas, his baby brother. I was even less a minstrel than he was a knight. Yes, I owned a battered harp. Yes, I practiced with it. But I had not been admitted into any guild, nor had I ever sung songs of deeds before anyone, let alone a king.

“You’ll have to do,” he said. I was just a boy. He didn’t give me any choice. He grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and hauled me onto his horse with no more effort than tossing a rag doll. He made sure I had brought my harp. It was there, in its case, thumping against my back.

That was how I found myself halfway around the world and halfway up the black mountain, battered, starved, exhausted, and in considerable pain since I had no iron shoes, and the knife-sharp stones had cut my boots and feet to ribbons. I had tied rags around my hands to protect them, but that hadn’t worked. I was a bloody mess. For much of the way, my brother merely carried me, strapped onto his back like an extra piece of luggage. Then he dropped me and my harp and his own pack down on the ledge, and I fell into a swoon, and dreamed that I was smothered in a vast ocean of corpses, all of them hissing curses through though broken teeth and bony mouths, not so much to threaten me but to complain to me, as if I could in my songs carry their grievances to the gods.

Then the dawn came, and their voices were merely the morning wind blowing over the mountain, and they shriveled away like paper burning in the sunlight, and the wind carried their ashes away.

I sat up, and saw my brother, tall and broad in his gleaming armor, standing at the edge of the ledge, reaching out with his sword as if to touch the sun and bring it up into the world.

That image would go into the song, I knew. I got out my harp and picked at the strings gently, enough to make my brother think I was already composing the song of his deeds, although I really wasn’t. I could hardly move my fingers, which were sticky with blood.

We ate of our meager rations. My brother tore up one of our blankets and bandaged my hands first, then my feet, sliding over them, not too gently, the remains of my ruined boots. Even so, I could barely stand, and only limp a few steps, so he once again rigged a kind of harness and carried me on his back like an extra pack. My back was to his, and I could only hang there as he climbed, gazing out into the bright sky, and across the plains below to distant lands, while my harp in its case, hanging by a strap, banged against my knees.

I must have slept for a time, by daylight, for I could only have been dreaming that pale, white faces floated in the bright air all around me, like masks, and I had a sense that they too wanted to scream curses, like the corpses I had dreamed of in the night; but for all their anger and sorrow, they had no voices at all, no breath. They drifted away from me like dry leaves on the wind.

#

Then another face appeared, as if wearing a cloak of black smoke or cloud. I wondered why my brother Altheric could not see any of this. Far away it seemed, at the very edge of my consciousness, he was busily battling monsters or scaling obstacles or otherwise mastering dire dangers, and so accumulating the episodes what would go into the epic of his deeds. But my brother remained oblivious to what I saw and what I felt and what I heard, and there was a white face floating above me, surrounded by swirling smoke. I could only see the eyes, which were wide and dark and perhaps more than a little bit mad, but at the same time filled with a terrible wisdom I could not yet comprehend or put into words. The rest of the face was a blank oval. When the thing spoke, the bottom part of it rippled slightly, but I did not see any mouth.

And it did speak, and it recited verses from the great song I was to shape and perform before all the world. It was not quite the song my brother might have had in mind, not just a rattling recital of his heroic feats or a cheery celebration of his brawn, but something stark and terrible, filled with the pain of death and the fear of the dark that is beyond the grave; a song spawned from those very shadows beyond the world from which even the gods turn away in dread.

All this I felt inside myself, as if I were truly a maker, a creator of song.

I sang of the Black Mountain.

But my brother did not hear any of that, nor did he see the speaking mask. Later that afternoon he shook me out of my dream by tossing me down on the ground again, alongside his pack. I struggled to my feet. We stood before the opening of a cave, out of which extended the skeleton of an enormous dragon. Scattered before it were the bones of a dozen men and scraps of rusty armor, broken shields, and broken swords. Here, I concluded, numerous heroes had perished, before that other hero, the one to whose epic our own was to be a sequel, had slain the dragon and made the way clear.

And the song continued.

My brother merely produced a dagger and pried two teeth out of the dragon’s jaw. They were as big as ox horns. These he tied to either side of his pack.

“Trophies,” he said. “I will present them to those I favor, when I have come into my fame.”

I would leave that out. Much of the art of the epic is leaving out the inglorious parts. You leave out every time the hero eats, sleeps, relieves himself, or steals dragon teeth from a monster he himself has not slain while intending to give the impression that he had.

With the dragon dead, the way was clear. He carried me and the pack and the teeth all the way through the hollow of the dragon’s bones, between its ribs, until we emerged from the other end of the tunnel and found ourselves deep inside the mountain, at the base of a flight of stairs that must have been made for giants. Now my brother was a large man, almost a giant himself. I barely came to his shoulder. But these stairs will made for someone or something larger still. All he could do was toss me and the pack and the horns up onto the step above him, then, with much effort, heave himself up, and do it again. Each time I cradled my harp, fearful that it would break. Each time my head or elbows or knees or my wounded feet banged against stone. By the time we had done this a dozen times, I was barely conscious. There were at least a hundred steps.

But all the while the white face in the cloak of black smoke hovered beside me or above me, and this time I could see skeletal hands, like enormous spiders, working something beneath the cloak. And the thing spoke to me, telling me that I was a true maker, and that the song which was like a dark river flowing through the many worlds of creation was within me, and flowing forth from me.

Far away, I heard the cries of circling dragons. I wondered if they were mourning for their murdered comrade, whose teeth my brother had stolen, or if they were longing for their master, or if the great song flowed through them too. Maybe all of these things.

My brother, Altheric remained oblivious to all of this. Perhaps a hero has to be such, to keep himself focused on his goal. He conquers fear by never considering the implications.

This I will keep in the song:

At the top of the stairs was only darkness until my brother drew his sword, which gleamed with the light of the sun, because on that first morning he had indeed reached out and touched the sun and made his sword magical thereby.

I wondered if there might not be a song flowing through him too, a bright one, telling only of exquisitely glorious deeds.

By the light of his burning sword, I saw that we had come before two large iron doors, like the gates of a castle, firmly locked.

Altheric set me down against a wall, on pile of stones, as if he were positioning a rag doll.

“Just watch,” he said.

His sword cut through the door as if it were made of cheese. The iron fell away in great ringing slices.

And I thought, Perhaps the songs are blended, his and mine, darkness and light, into the true song of the Black Mountain.

Or perhaps not.

His next move was not the stuff of epics.

Beyond the door lay revealed a vast hall carved out of the heart of the mountain. On every side stone arms and hands held aloft stone torches; and as we entered, my brother carrying me under his arm like excess luggage, the stone flames of the torches began to glow with pale white light as we passed. I could see all that lay beyond: pillars grown out of the floor or ceiling and shaped into the gigantic images of solemn wizards, some with the heads of beasts, as majestic as gods, but not, I think, any gods than mankind has ever known.

On each side were what looked like stone coffins.

I felt the presence of ghosts everywhere. This was a place of death. Couldn’t my brother sense that?

Apparently not.

Beyond the entrance hall the procession of the pillars curved off to either side, and in a further room was heaped with an almost infinite amount of treasure, gold and gems and pearls, precious swords and cups and jewels and so much more, all of it glowing of its own light, the whole mass of it like a brilliant sunrise held captive within the Black Mountain.

I wonderful if what the mournful dragons really longed for was to rest upon these riches. They say dragons do that.

I wondered why the previous hero who had come this way, the one who had slain the Sorcerer, had not taken any of this treasure for himself. For it is not recorded in his own song that he came back with any prize, only with the news that the Sorcerer was dead. It might be that he was strong enough not to be corrupted by avarice. A true hero indeed.

Yet my brother danced among the gold and jewels. He ran his fingers through the heaps of them, letting coins and diamonds and the like rattle down between his fingers.

He was like a delighted, greedy child, I thought. This couldn’t go in his song. Not if he was to be the hero of it.

“I don’t have to worry about any recognition from the Great King,” he said. “With this I can buy the world!”

#

The rest can be told quickly. The song that flows through me is the song of the darkness between the worlds, the song of the shadow that hides the light and devours it. I don’t think my brother will figure very largely in it.

“Look,” he said, pointing.

I looked. There at the far end of the room, on a raised dais, was a high-backed throne, to which a desiccated corpse in a black robe was pinned with a spear. Its bare skull leaned forward. A crown of polished white bone had fallen into the corpse’s lap.

I did not doubt that we were in the presence of the original Sorcerer of the Black Mountain.

My brother merely laughed at the sight, pulled out the spear and threw it aside. I saw that it was covered with runes that still glowed faintly.

Then he swept the bones from the seat in a cloud of dust, and sat down. He put the pale white crown on his head, and like a drunkard imitating a king he raised his hand to indicate all he surveyed.

“It’s mine now. All mine.”

Very stiff and sore where he had tossed me onto a heap of coins, I could only look up at him and gasp faintly, “What happens next?”

“What do you mean, what happens next?”

“An epic song can’t end like this. There has to be a great deed. A sacrifice.”

He looked around. He shrugged. “I come back a hero. I am fabulously rich. I can buy whole kingdoms, have any woman in the world to wife, raise a brood of strong and heroic sons who will one day help me knock over the Great King of All the World Worth Ruling like a chess piece, and we all live happily ever after – maybe even you, little Valas, if I find a place for you in my court. It’s not a conventional ending, I know, but I like it very much. Maybe the epic form needs innovation. Yes.”

And I spoke with a deep and thunderous voice which was not my own, saying, “This is not how the song ends.”

And I took up my harp and played upon it the music of the great song which flows out of the shadows.

Altheric looked at me amazed, even a little bit afraid. I rose, using some strength that was not my own, and he followed when I commanded. The wall behind the throne opened, the stone peeling away like a curtain, and another staircase was revealed, this one human sized. I set foot on it, and the step was very cold, with the cold of the spaces between worlds, but I felt no hurt. My feet and legs were numb. It was like walking stiffly, precariously on artificial legs of iron, but I made my way, all the while singing in a voice that was not my own of terrors and of the dark and of the true hero who alone can overcome them.

Perhaps my brother was flattered, thinking he was that one true hero after all.

Perhaps he was just a fool.

We stood before a vast, arched window open to space. We must have been at the very summit of the Black Mountain, or perhaps somehow beyond it, for we looked down on stars and worlds, not on the plains of the earth.

“The purpose of your quest,” I said, “if you are any sort of proper hero, is to remove from this haunted mountain the evil that has come into it. To cleanse this place.”

“To cleanse it of what exactly?”

“Of greed and falsehood and foolishness and vainglory, which are the cause of most of the suffering in the world. Great would be the hero who could rid us of them forever.”

“Great is the hero –“

“Look down there,” I said.

He leaned out the window to look, and I pushed him through, and he fell screaming for a very long time, until I no longer heard him screaming. Several stars flickered, as if something had moved across them, converging on a point, the way fish do when a morsel is tossed to them.

#

This is not the end of the song. It is barely the beginning.

In a later part of it, I, Valas, the boy who never quite became a maker of songs but became part of one, sat on the throne of the Sorcerer of the Black Mountain with the crown of polished bone on my head and a robe of black smoke wrapped around me. I felt no pain from any of my wounds and my bandages fell away; but I was filled with terror and rage and wonder. The pale white mask floated in the air before me, speaking, and I put it on, and then I was not longer Valas, who might have pushed his brother out the window merely because he was insufferable. Instead I had many names and the memory of many lives, and I understood that in the fullness of time the ancient body of the Sorcerer of the Black Mountain could no longer be sustained, even by magic. Therefore, enfeebled, barely able to remain seated on his throne, the Sorcerer sent dreams out into the world, inspiring heroic songs, which brought heroes to the Black Mountain. Several of them, pretenders and otherwise inferior, perished, but in time a great hero – whose deeds are well told in story and song – had fulfilled his quest and slain the Sorcerer as he wished to be slain. Thus his ghost and all the ghosts of those he himself had slain and made part of himself over the centuries might enter the dreams of men and inspire yet another quest, with a somewhat different ending in store for the hero. (Yes, the epic form is capable of innovation.)

As it worked out, it wasn’t the hero who provided what was needed. The singer, the maker, became part of the song.

Valas is only fourteen years old. With magic, he might last a thousand years, this composite, who is the boy and the sorcerer and all the ghosts of the Black Mountain.

I am they.

I know that half a world away, the Great King in his palace has declared a quest. The trumpets blare. Soon a champion of light will come to confront the darkness.

I stand atop the Black Mountain. I reach up my hands. I call down my dragons.

I am ready.

The song continues. We are shapers, but not makers. The song flows through the world, through us. At best we can direct it a little bit, give it outward form.

But it goes on, of its own accord, like a black current that arises at the center of the universe and flows between the stars.

This is not the end.

________________________________________

Darrell Schweitzer is the author of We Are All Legends, The White Isle, The Shattered Goddess, The Mask of the Sorcerer, and The Dragon House, plus nearly 300 short stories, which have appeared in venues ranging from Fantastic, Realms of Fantasy, and Interzone to Andrew Offutt’s classic Swords Against Darkness series and all six volumes of S.T. Joshi’s Black Wings. He has published books on H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Lord Dunsany, Thomas Ligotti, and Neil Gaiman. He was co-editor of Weird Tales 1988-2007 and remains an active anthologist (Cthulhu’s Reign, The Secret History of Vampires, That Is Not Dead, The Mountains of Madness Revealed, etc.) He has been nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award once and for the World Fantasy Award four times and has won the WFA once.