THEN, STARS

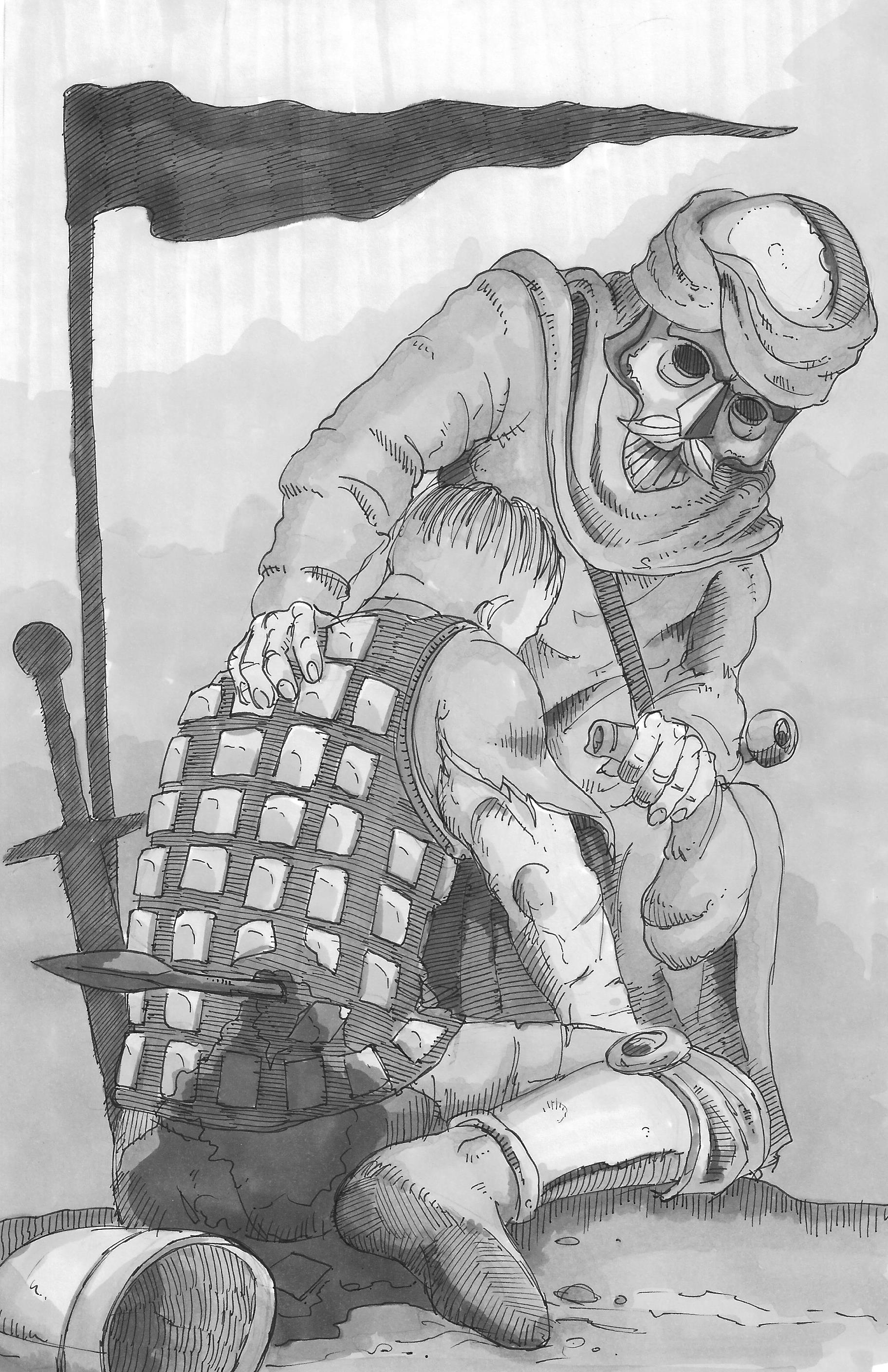

THEN, STARS, by Michael Meyerhofer, Art by Simon Walpole

I know nobody cares about a squire’s dying words, but Eli Ben-Sodr insists it matters, and he’ll write down whatever I say just as I say it, so I guess I’ll humor him. Gods know he’s been kind to me, even though he could have just left me on that battlefield. Well, I’m not sure where to start so I guess I’ll just begin with what got me in a dying way in the first place.

By the time Eli found me, I’d already been lying in the mud for two days. Don’t know how I was still alive, except that spear must have gone in right below my lungs—through the front of my brigandine and out the back—and the shaft kept the hole plugged up. I remember I was fighting this robed swordsman with a silk mask covering his face. The mask had yellow tassels that bounced when he moved from side to side, like he was made of water. But I’m quick, too. I had him. Only I was so busy carving the light from his eyes, I didn’t see the other Shii-duán rushing in.

Then, there it was. The spear, I mean. I remember I grabbed both ends to hold it steady—thank the gods I thought of that!—and bent my knee to the bloody earth, slow as a knight taking his vows. Only I’m not a knight, just a squire.

My lord is Sir Bryson of Akonbree. He won the tourney at Scottskarl last spring, right before the war. His lance put Sir Varris and Sir Makon on their asses, then his morning star cracked the visor of Sir Ulrich’s helm—Ulrich the Undaunted, they used to call him—and would have crushed his skull, too, if the king hadn’t called a stop to it. Sir Bryson. Bryson the Brave.

Bryson the Bastard, more like it!

He was maybe four steps away when I took that spear. By the gods, I only took it because I was trying to guard his back. But he barely spared me a look, then he shook his head and muttered something about avenging me and charged off. And there I was, lying in the mud, bleeding my guts out.

Oh, I’m sure he killed a dozen enemies in my name, though I’ll bet he didn’t even remember which squire he was avenging since he’s had so many of us die in his shadow lately. Anyway, back to the battle, since I know that’s what you really care about.

For a while, it looked like the knights had it this time. But that didn’t last. Hell, we’d lost the last two battles, so why should the third be any different? I remember lying there, breathing shallow, watching those Shii-duán scimitars dance circles around armored knights with their greathelms and two-handed swords. Then the Shii-duán snuck a corps of archers with those devilish composite bows up behind our lines, and they started shooting, and that pretty much sealed it. All that talk of honor and glory, but when the trumpets fade and the sun goes down, the dogs come. Wolves and vultures, too. And people.

Usually people means looters, meaning people who’ll cut your throat and take whatever you’ve got left. I’ve seen it before. Their shadows scrape the field like crows. Only this time, the shadows belonged to Shii-duán peasants. They drove off the crows and tended their own wounded. Had this been a battlefield in Kingsland, they would have stolen what they could, taking what the dead would not miss anyway. All those riderless horses, all that steel and silk laying around, enough to make poor men rich. But Shii-duán are a strange lot. They’re funny about touching corpses, let alone robbing them.

Anyway, some of the Shii-duán were going around with knives, offering mercy to whoever asked for it. One knelt in front of me. I couldn’t understand what he was saying but I got the point when he touched the hilt of that long, curved knife at his belt. I shook my head. He looked surprised. He pointed to the spear in my guts, then up at the crows circling in the twilit sky. He touched the hilt of his knife a second time. I shook my head again. He shrugged, got up, left.

It was quiet after that. No more cries or whimpers, just the rustle of feathers. But the crows kept away from me, what with all those easy pickings on the field. I figured I’d go soon but the hours wore on and I kept drawing these slow, painful breaths. Half my body went numb. Everything blurred. The sun sunk behind the hills and everything went from blue-black to just plain black. There wasn’t even a moon. I kept falling asleep then jerking awake, one numb fist still gripping the muddy shaft of that spear. I don’t know why I still had a hold on it. Gods know it wasn’t going anywhere!

Then the wolves and wild dogs showed up. I heard them tearing, smelled the salty raw meat they were fighting over. That shook me but for once, they had more than they could handle. I don’t think they even visited half the dead men littering the ground that night.

There would be other nights, though. When I saw those first pink ribbons of dawn, I got this wild thought that maybe I’d live after all. Maybe Sir Bryson would come back for me. Or maybe the knights would send monks to tend the wounded. Maybe they could even find a way to take that spear out without killing me, and I’d get a fat purse of silver for surviving and get sent back to Kingsland, far away from this ass-stink of a war.

But somewhere in my head, I guess I knew that was just a mud-scraper’s dream. Even if the gods were kind for once and I survived, they’d probably just send me back to the front lines. If I couldn’t swing a sword, they’d give me a crossbow, post me on a ridge, and tell me to shoot men in the back or rain death on crying Shii-duán peasants. That’s the way it is for us. No way out.

I remember lying there, my blood slowly leaking out, thinking it was funny that it didn’t hurt more. Of course, when you get your blood up in the middle of a battle, you hardly feel a thing. But this was the next day. I figured I’d be in agony. I’d heard bad stories about men who got gut-stabbed and screamed for a week before they died. I didn’t want that.

I looked around and saw my shortsword laying there in the mud, just within reach. It was plain but sharp—I knew because I’d worked it for hours myself with oil and a whetstone, once I was done tending Sir Bryson’s blades. I thought it over. No sense hoping for the impossible. No sense lying there in agony, either.

Only this doesn’t hurt so bad, I thought.

Oh, I’d get a shock of pain once in a while. I don’t mind telling you I’d grit my teeth and cry like a beaten child. But mostly, I just felt like everything but my head had gone to sleep. And what’s the rush in ending that?

As it happens, I was facing east. I watched the sun rise nice and slow, quiet as a fish. Funny, I don’t think I’ve ever really stopped and watched a sunrise before. Well, maybe when I was a boy back on the farm, but probably I was thinking about how much except how I hated my father, or how much I wanted to impress the blacksmith’s daughter now that she was getting round in all the right places.

Nothing’s round as the sun, though. I watched it go up—I almost said I watched it go up like an arrow, but I think it’s sad that the only thing I can think of is an arrow, something tipped in death. Then again, what else is there? Birds, I guess, but crows are birds too, and they’re happiest when something dies.

I had a powerful thirst by now. The thirst was the worst part. I got the idea that maybe I could crawl toward the corpse of some dead knight, since they almost always have flasks of wine on them. But my arms barely worked and that spear was so heavy, so heavy.

I passed out again—much longer this time, so long I’m surprised I woke up at all. When I did, I saw Eli Ben-Sodr kneeling over me. Only I didn’t know his name yet. He was kneeling over me, checking my wound, and he jumped when I opened my eyes.

(“I didn’t know you were still alive,” he says now, writing this. We laugh. I wonder if he thought I was a ghost.)

I don’t much remember what happened after that but he says I asked for water—which he gave me—then I said I was sorry he was destined to burn in the gods’ cauldrons, since that’s what the priests tell us. I asked if he meant to kill me. He asked if I wanted him to. I said no.

I don’t even think it occurred to me then to wonder why this man, this enemy, knew kingspeech as well as I did, but I remember I asked him later. He said it was because he was a merchant. He used to live in Bywater, trading bright silks to the knights before the war. Hell, his hands might have handled the silk that made Sir Bryson’s tabard! Funny, if you think about it.

Now, he helps his brother train horses for battle. He says he likes trading silks better. Then again, a lot of us probably prefer whatever it was we were doing before the war. Anyway, Eli says he left—he says I pleaded with him not to go, but I don’t remember that—but he couldn’t bear the thought of me just lying there, so he came back later with his sons. They didn’t say much but they helped me on some kind of cart.

I’m no poet so I don’t have words for how much it hurt when they moved me. I don’t remember screaming but they say I carried on so loud and pitiful, one of Eli’s sons wanted to slit my throat—maybe mercy, maybe nerves. Only Eli stopped him and I passed out instead. They took me to their home. I slept most of the way, but when I woke, the hurt wasn’t as bad. I looked up and saw the first tendrils of moonlight peeking behind a dark sky, like bare parchment peeking through spilled wine. Then, stars.

Eli says I groaned and cried from time to time, that whole way as I was lying in the cart. I don’t remember that, either. But I remember when they lifted me out of the cart and took me inside. It was like my whole sleeping body woke up, all at once, and everything hurt so bad I couldn’t breathe fast enough to scream. Eli says I pleaded with them to put me down, to just kill me after all. I do remember that. But they didn’t listen.

They got me inside, laid me on my side on a soft mat of straw. There were candles all around me. They even gave me more water. Then they got a strange curved saw and held the spear steady and sawed off as much of it as they could, front and back. Then they cut off my brigandine. The dried blood made it stick to my skin but they softened it with water and peeled it off in strips. When they were done with that, they washed the wound with that bit of spear still inside me, and covered me in blankets.

After a while, they gave me wine. Eli says to numb the pain, but I think it was to quiet me down. Eli has a little one, a daughter with big green eyes, and I saw her peeking out from behind her mother’s legs. I’m sure my screams were scaring her. I winked at her but I don’t know if the Shii-duán even know what that means. For all I know about their people, I was insulting them. I hope not, though. Gods know they were treating me better than Sir Bryson treated those Shii-duán peasants we captured last month.

Once the wine kicked in, my body went numb and I didn’t feel so bad anymore. So we talked, and Eli explained the mess I was in. He said they could cut the rest of the spear out of me, but right now, it was plugging up the wound. So if they took it out, odds were probably bleed to death before they could stitch it up. On the other hand, I’d die slow if they left it in. They asked me what I wanted them to do. I said I wanted them to make it so none of this ever happened.

Eli laughed. “Such things are beyond my skill, my enemy.”

I know he was calling me enemy, but it didn’t sound like he really meant it. I guess it isn’t like I posed much threat, lying there like that, helpless as a baby. Not sure what I said after that because I passed out, but I remember the dream I had.

I was back on the farm. I was still a boy. It was the day Uncle Jorie came by. He was squiring for Sir Alstair of Duskwheel and he said he’d heard that Sir Bryson’s squire had just taken an arrow through the eye. He said he could put in a word for me. If I wanted, Sir Alstair might even introduce me to Sir Bryson, and if the latter said it was okay, I could go to Akonbree and live in a keep with fires and food and mead whenever the lord wasn’t looking.

Father said no. He’d had a brother who squired only the knight didn’t feed him worth a damn, so my uncle got his hand lopped off for stealing a wheel of cheese. They heated the blade but the wound festered anyway and that was that. Father had a point. I wasn’t dumb enough to believe those stories about knights and honor by then. But I was tired of cabbage and turnips. So in real life, I packed what I could and left without his permission.

In the dream, though, I accepted what Father said. I stayed home and did my chores. I grew big and strong and pretty soon, Father stopped hitting me. I even won the heart of the blacksmith’s daughter, and we had children in a little cabin by the stream, next to a golden sea of crops, miles and miles from the war.

When I woke up, Eli asked if I wanted him to write a letter. He said the Kingsland monks would accept a letter from him, if I wanted to write to my family. I said there wasn’t much point. Everyone was dead—father and mother from the plague, Uncle Jorie from a scimitar. Maybe some cousins somewhere, maybe somebody back home remembers me, but really, I’m nobody. The world won’t even notice I’m gone.

But Eli wouldn’t drop it. He said that among the Shii-duán, the last words of anyone—even an enemy—are considered sacred. If nothing else, my words would be written down and stored in some temple of theirs, where their priests will read it like gospel. Imagine that.

I remember in Sir Bryson’s keep, there was this one room full of books. Whenever I wasn’t training, I’d go there. Sir Bryson never bothered with them, and I can’t read (though I liked to look at the pictures), but one of the servants who tended his ledgers told me about them. He said they’re full of tales and histories of the great houses. So many books about kings and usurpers and knights who rose to their station by hating whatever it was they used to be… but not one single story about the people they left behind. The ones without armor, who smell of turnips and cabbage until they bathe in the same river that waters their cattle.

I guess there’s no point in reciting my lineage. But I’d like Sir Bryson to know, in this world or the next, that I was the sword that guarded his back while he howled oaths at the wind. And my uncle Jorie played the lyre better than any court minstrel. And my mother had green eyes, green as the gardens around his keep that I tended with my own hands, whose thorns tasted my blood. Green as the eyes of Eli Ben-Sodr’s daughter as she brings me this last cup of cool water.

It’s late now. Getting harder to breathe. Eli’s wife opened the windows so I can feel the night breeze. I can see this snowy glint through the clouds, angling off the crosshatch of the straw mat were I lie, waiting on them to drag the last of this spear from my chest. The moon’s fattening up. I wish I could see it whole, but that’d take too long.

I don’t mind telling you—whoever you ends up being—that I’m afraid. I know I should pray to the gods like I was taught when I was little, like I’ve done a thousand times before, but suddenly I can’t remember a single line. Now, Eli’s wife is talking over me. I can’t understand the words, but I think she’s praying. Imagine that: an enemy, praying for me.

Eli’s daughter just came out and took my hand. His sons are kneeling all around me, holding clean rags and gruesome tools heated in boiled wine. His wife’s still praying but she has a needle in one hand and thread in the other. Eli says I should close my eyes now. But as scared as I am, I have to leave them open. I don’t want to miss anything, no matter how terrible.

I guess this is it. I take a deep breath and hold it in as long as I can. Then I look at Eli, who’s still writing with one hand and holding an iron pincher in the other. I don’t know what to do, what to say, but I’m grateful for all this kindness I don’t deserve. So I look at him, I take another breath, and I tell them I’m ready.

________________________________________

Michael Meyerhofer is a fantasy author and poet whose works include the Dragonkin Trilogy, the Godsfall Trilogy, and several books of poetry. His stuff has also appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, Orson Scott Card’s InterGalactic Medicine Show, Strange Horizons, and other journals. For more information and an embarrassing childhood photo, visit wytchfire.com.

Simon Walpole has been drawing for as long as he can remember and is fortunate to spend his freetime working as an illustrator. He primarily use pencils, pens and markers and use a bit of digital for tweaking. As well as doing interior illustrations for various publishing formats he has also drawn a lot of maps for novels. his work can be found at his website HandDrawnHeroes.