WE WHO ARE ABOUT TO DIE

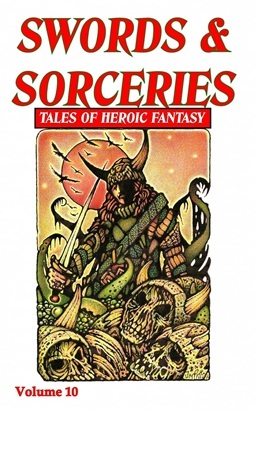

[WE WHO ARE ABOUT TO DIE, by Michael W. Cho, artwork by Robert Zoltan

Libyssa was always like this.

Wrapped in his famed red cloak, Chylon strode down the abandoned streets of the town, coming from his meeting with the king. He squinted his one good eye as rain beat on the stone-walled houses and packed-earth viae. The gloomy bulk of Mysian Olympus blocked out half the sky. On the other side of town lay the sea, flat and dull like black ice.

He had served many employers, each stop in his wanderings a bit more unpleasant, a bit more squalid. Chylon was not his real name, of course. He had too many enemies for that: so he had taken the name of the Spartan sage most famous for advising, “Do not desire the impossible.”

The front room of Eudoros’s house smelled of sour wine, smoke, and body odor. A few men huddled around a candle-lit table, looked up and then turned away. Chylon gave away nothing. He grinned and nodded to them, then warmed his palms by a low fire that glowed in the fireplace. Age spots and loose skin were plainly visible even in the gloom.

Eudoros, a round-backed man in his forties with a sparse brown beard and a balding head, crept across the room. His house doubled as the tavern and brothel with one worker, his daughter.

“Where is Rhene?” asked Chylon.

Eudoros twitched his shoulders—his way of shrugging when spooked.

“What is it, man?” Chylon smiled broadly with an ease he didn’t feel. Prusius, the king of Bithynia and thus Libyssa, had brought him in as a military advisor to fight Rome and her proxies. It had gone well. They’d won their last naval battle by catapulting vases full of vipers onto enemy ships. But Prusius had lost his nerve: Chylon could sense it.

Eudoros grinned like a levy ordered to charge archers. “Nothing, nothing at all. Rhene’s out getting some eggs and also visiting a healer for headache. She’ll be back soon. Let me get you a plate.”

Chylon pulled out a bench at an empty table, studying the others without seeming to. In the six years he’d resided here, he’d taken the time to get to know the locals. Most of the men were staring at their drinks. A painful tension settled in Chylon’s stomach. He kept up the grin until Eudoros returned with wine, a platter of meat, barley cakes, and boiled leeks.

“If ever we have honored you, poured out sweet wine in reverence, hear now our prayers, grant us your blessings,” Chylon intoned, and then sipped wine sweetened with sugar of lead. Eudoros disappeared through a curtained doorway.

Chylon chewed the mutton slowly. It reminded him of short rations and long marches, of meals shared with men of every shape, skin tone, language, personality. He had been the supreme commander of almost every army in which he’d served, and always shared the discomforts and perils of the common soldiers.

“A word, General?”

It was the blacksmith, Bais. His daughter and son-in-law lived in one of the mud houses Chylon had constructed and given away. The others were filled with young couples, grandmothers, or simply folk who preferred the new houses to their old ones.

No one questioned why he needed to dispose of so much dirt from his villa.

At Chylon’s gesture, Bais took a bench and leaned across the table.

“General,” he said in a low voice reeking of wine. “It’s the Romans. Heard they came in two nights ago and had an audience with King Prusius. So says my brother-in-law.”

Prusius had said nothing to Chylon about the Romans, who had placed an enormous bounty on his head, some said 2,000 talents.

At Chylon’s nod, the blacksmith returned to his cups.

His insides had gone very cold. He had misjudged the situation badly. It was time to flee yet again. If the Romans had gotten permission from Prusius to go after him, they’d try to catch him in town, and perhaps set up a perimeter around his villa.

Low voices came from the other rooms, almost making him jump. Shortly, Rhene swept through the curtains. Her pale linen tunic could not hide her long-legged shape. Normally the townsmen would ogle her and offer bawdy comments, but the glum mood didn’t lift as she moved among them, picking up a plate here, filling a drinking cup there. She had curly brown hair and large brown eyes. The skin of her cheeks was marred from acne in her youth, yet she was popular and had taken each of these men into the back room. She was a profitable asset for Eudoros.

She ended up standing before Chylon, looking down at him with her unreadable smile.

“General, welcome. More wine? Is the lamb to your taste?”

He stood and kissed her on her pocked cheek. “I’ve worn armor more tender than this mutton.”

She poured from a clay amphora efficiently, precisely. A widow who had come home to live with her father, Rhene had seen thirty summers. Chylon had first taken her as a customer in the back room, later as a lover at his villa. They had talked of marriage, but only in the way people talk of strapping on wings and flying among the clouds.

“Sit with me, love.”

Rhene perched on the bench next to him and leaned her soft, young body against him. It was no secret in Libyssa they were lovers.

“You’ve heard talk of the Romans?”

“Yes.” Her face was as calm as a statue of Tanit. “They are outside.”

Chylon’s heart thumped rapidly. Apparently fear still functions within me. He glanced at the front door, which he sat facing by habit.

“In the street?”

“Come from Nikomedeia.”

The curtain to the back rooms drew apart, but it was only Eudoros. They followed him into a narrow corridor leading to the rest of the house, ending up in the warm, smoky kitchen. A black pot simmered over a fire.

“General, Rhene’s told you of the danger,” said Eudoros, tripping over the words. “You must take the trail near the pond. That’ll be safe.”

Eudoros was looking at the ground. His face was pale, his small hands clasped before him.

“Nowhere is safe for me,” said Chylon with cheer he did not feel. The trap was closing once again. The Romans had pursued him from country to country like a wolf pack on the trail of a weary stag.

“May I have a moment with your daughter?”

Eudoros bobbed his head and disappeared.

“I knew this day would come,” Chylon said. “The Senate won’t rest until I’m dead. And King Prusius—“

“—is a coward,” said Rhene.

Chylon nodded. “In a sea-cave, I have secured a boat with provisions. I intend to offer my services to the king of Pontus. I won’t be coming back… I want you to come with me.”

Rhene said nothing. She did love him, he thought. He had helped Eudoros through some rough times and given Rhene everything except promises.

“My father—“

Eudoros had whored her out as soon as her mother died. “Can run this place himself.”

“He has debts you don’t know about. More importantly, if I leave, the Romans will suspect—they will know. They may punish him.”

Rhene had a point. Romans were vindictive, as Ba’al and Zeus and Jupiter knew. There was no time to press the point. Assassins would be surrounding this tavern or infiltrating his villa at any moment.

He embraced her and kissed her cheek. “I love you, young one. Meet me by the obelisk at midnight if you wish to come with me. Otherwise, farewell.”

Chylon went to Rhene’s much-used bedroom, put a chair against the stucco wall, and wormed his way through the high, small window, gritting his teeth against pain in his joints. Twenty years ago it would have been no problem at all—well, perhaps thirty.

He caught hold of a slippery gap in the wall and lowered himself to the alley. It was getting near dusk. The air hung thickly with cold moisture. His signature red cloak he unfastened and folded so its exterior color could not be seen. His eye patch he stuffed in a pouch—it marked him just as surely.

Chylon crept along the wall between Eudoros’ house and the adjoining building until he could get a look at the trail that ran about ten feet below the level of the town. The path was strewn with offal, feces, and potsherds, and haunted by jackals and rats. On the other side was a reed-choked pond inhabited by unusually silent frogs.

The skin along Chylon’s spine tingled. The reeds did not appear disturbed, but mud bloomed on the surface of the pond near the path. No. He would take another path home.

Chylon headed straight toward the center of Libyssa in the hopes of losing himself among the workers and craftsmen who’d be heading home around this time. No Romans made themselves visible. Perhaps they were scouring the outskirts of town. Or hiding in a doorway and waiting for him to make his move.

He joined up with a group of grimy dockworkers trudging in the same direction. By the time it was dark and a cloud of rain had engulfed the road, he was able to slip, unobserved, into the fields and make his way to his villa by a circuitous route.

It stood on a hill a few miles from town. As the rain ran down his face and soaked his tunic, he contemplated the villa’s darkening silhouette on the bush-strewn rise. It was too dark to see anything. His hunters would be killers, hard-eyed, young, fanatical. Burning to carry his head back to Rome in a box. The wise course of action would be to head straight to the escape boat.

Yes, he would run. But first, he’d give them another tale to frighten Roman children by.

Chylon snuck over to the shed at the boundary of his property. There he saddled a whickering pony, and attached a pole to its saddle. To this, he fastened a lantern, and with a smack on its rump, sent the pony galloping along a pre-arranged route leading to the mountains. It disappeared into the night, a yellow spark bouncing in the darkness. He grinned. Hadn’t used that trick since Campania.

As he crept toward his villa, two shapes detached from the shadows and ran after the pony. Ba’al’s blessing was on him! Chylon slipped through the marshy area they’d occupied and made his way to the front door of his house. In response, there was a scuffling sound off to one side. He took off in a dead run to the front door, unlocked it, entered, and hurriedly barred it.

That had been relatively easy. In a sense, he’d trapped himself inside his house, and they now knew his location. But here he had allies—two Molasser war-dogs he’d raised from pups.

His breath rasped in his throat as he peered deeper into the house. Lamps in sconces flickered in the passageway ahead. Phrygios would have lit them. His Cretan servant was the same age as Chylon but usually retired around dusk.

He crept to a niche off the vestibule and removed a tapestry from the wall. Behind it was a square cavity backed by a plate of polished silver tilted diagonally to him. Dusky images swam on the mirror. The contraption, which consisted of a series of four expensive mirrors, was much more useful in the day. It was too dark to make out any details, but it clearly showed six distinct shapes–men moving around the periphery of the house, some climbing up its walls.

Chylon replaced the tapestry and made his way toward the atrium. It was open to the sky, with the clay roof sloping inwards so that water would run toward the fountain. A steady, quiet stream did so now.

He almost tripped over something bulky on the ground. Phrygios? No—he knelt and felt a dense, furred pelt. His two mastiffs, Phobos and Deimos, lay on the ground, dead. Each weighed as much as a man and would rip out the throat of any unknown intruder. Chylon had spent many hours training each of them. Neither had any evident wound. They’d been poisoned—but how? They would only eat from people they knew.

Phrygios.

Now all he had left in this world was Rhene and—Rhene had as much as told him that she wasn’t coming with him. Chylon closed his eyes and took a deep breath. He had once decided the destiny of armies and whole cities. He was surrounded by enemies, alone once again.

It was an effort to rise to his feet. Then a heavy shape dropped from the roof, smashing down on the ceramic ridge surrounding the fountain. A cry from above followed and another windmilling, falling shape.

Chylon dropped to one knee and plunged his dagger into the closest man, whose body lay half in the fountain. The other man tried to push himself up with one arm. Chylon took two steps and kicked him in the face, sending him twisting and inert to the floor, out cold.

He pulled him up by his black hair. A Latin for sure. Blood trickled from his long nose, his mouth hanging open. The other half-floated in the fountain face down, but Chylon wasn’t inclined to rescue him, if he still lived.

He glanced up at the rectangle of murky sky rimmed by protruding clay shingles. Every season, he got on a ladder and waxed the lower ones around the compluvium so that an invader would suddenly find the footing very slippery indeed.

At the very least, four Romans remained.

Holding his knife in front of him, Chylon advanced to his study, a small room with a table and chair and lined with bookshelves. He moved aside several layers of priceless scrolls and pried open the false back of a shelf. There he found his espasa in its sheath, which he strapped around his waist, and a Balearic sling, which was a leather pouch connected to two lengths of rope. A weapon the Romans always had underestimated. This he tucked in his belt, along with a pouch of river rocks and another pouch of tetradrachmas minted in several different kingdoms.

It pained him to leave his library, which included books on military strategy he had written. He circled back through the atrium, which was empty but for two canine and two human bodies, to a storage room near the front door. It was full of boxes and large amphorae and barrels. Ears alert for sounds from the rest of the house, he moved aside several of these. Chylon scrabbled in the darkness until he found a crack in the wood planking. Below lay a tunnel that let out a hundred yards from the house. He stuck the dagger in the crack and carefully pulled up the trapdoor.

He slammed it shut. A heavy weight slammed upwards into it, forcing it open again. Glinting steel tore into his thigh. He caught a glimpse of a savage face, and he drove the sole of his boot into it. The man grunted and fell. Shouts came from below—there was more than one of them. Chylon sprang to his feet, slammed the door shut again, rolled a barrel of water onto it. He threw bags of grain and beans on the pile until he had several hundred pounds weighing it down.

His head spun, not from exertion but from the thought of his escape tunnel being compromised.

Phrygios had suspected the existence of the tunnel, perhaps. If he had tipped the Romans off, they could have searched at the base of the hill and found the exit. But that would have taken time, and the Romans had not been in the area for long.

The only other person who’d spent time in the villa had been Rhene.

She could have poisoned the dogs. She could have told the Romans about the escape tunnel.

But why? No. She would not have done it.

He shook his head against the wave of bitter regret. The men below were quiet. It was too much to ask that the man who’d fallen had bashed in both of their brains in a freak accident. They’d leave the tunnel and find another way in. Get a log and knock down the front door, if it came to that.

His left thigh burned from a deep cut six inches long. Chylon had seen many wounds in his line of work. This one would leave a scar and a limp. More importantly, it would hobble him for the present and could bleed out if he didn’t get it bandaged.

He wrapped up some rags and tied them around his thigh. It was a rough job, but would do.

Chylon slipped the espasa from its sheath and ran his thumb along its edge. Two feet long, it was double-bladed and ended in a wicked point. In his day, Chylon had been a master in its use. But his arm was not as strong as it once had been, and now he had only one good leg.

He shambled through the atrium and into the garden, the night dark and wet and cold and framed by olive trees. Strange shapes on the lawn could be men or monsters or marble statues. All still but the feather droplets of rain caressing his face. Phrygios’ window faced onto the garden, but it was dark, as was usual.

Chylon skirted the periphery to the back wall, which was a mosaic of a great swan chasing a girl across mountains and rivers and forests. Zeus and Leda. He brought his face up to the eye of Zeus. It was a glass bead attached to a hollow cylinder piercing the wall, with another lens on the other side. Chylon had constructed it. Through the wide-angle lens, he saw shapes and the gleam of metal. Two men with their backs against the wall, one on each side of the secret door he’d installed in the mosaic. He was trapped.

“General.”

He whirled, espasa at guard. Standing on the rain-flooded walkway leading from the atrium was a large man, sword dangling from his fist. He was tall, well-built, and his grin made his lantern-jawed face look like a skull. He had the poise of an experienced fighter and the limber bulk of youth.

The assassin chuckled. “Look at the shrunken old man. Like a rat in a roasting pot. Hard to believe this is the bogeyman of my childhood. That Mother used stories of you to scare us into doing right. Killing you will be immensely satisfying.”

Chylon dropped the espasa onto the soggy ground.

The Roman let his large head fall back as he laughed in a booming voice. “The great one is too scared to even cross swords with me. What, bending your head to the knife like a–“

The Roman’s eyes widened and he cut off his remark, likely aiming to throw himself to the ground—but too late. There was a crack, and then the Roman twitched and slumped slowly to the ground, eyes bugging out, mouth open. Chylon tucked the sling back into his belt. As he had hoped, the Roman had misinterpreted the movement of his body as submission. The smooth rock had flown in a deadly arc and caved in the front of the assassin’s skull.

Still, he was trapped. His legs felt leaden. Chylon dropped to one knee and then laid his back against the wall. It was over. He wasn’t going anywhere.

A pale shape moved hesitantly into the garden from the corner. His servant, Phrygios.

“It’s cold and raining. I heard sounds.”

Chylon only breathed deeply and watched Phrygios’ face. His visage, like his master’s, was wide, hook-nosed, lined with the years. He also had gray curly hair. In fact, one reason Chylon had hired him was because he resembled him. Sometimes it was advantageous to have a man who could pass for his master.

“Two hours ago, the dogs were barking. I stayed in bed, because they stopped barking. And–I was afraid. Master?”

“There are intruders, Phrygios. Romans. Here to bring my head back to the Senate. They seem to have trapped me quite thoroughly.”

Phrygios quailed. “What will you do, Master?”

Chylon sheathed his sword, which his servant noticed. The general removed the ring from his finger and twisted off the emerald from its setting. Underneath was a glass capsule, which he broke. With a ferocious growl, he seized Phrygios by the neck and jammed the ring into his mouth. He rubbed it on his tongue and scattered the powder, held his mouth shut until he swallowed. Phyrgios gagged and coughed.

“Guh–?”

“It is aconite. Meant for me, so that I could not be captured alive. It will be over in a few minutes.”

“But why?”

“Because you betrayed me.” Which I must believe…

“No!”

Phrygios clutched his stomach and sank to his knees. He coughed and choked, face contorted, howling soundlessly. Chylon watched dully. It was not a pleasant sight. When Phrygios stopped moving, Chylon opened up his red cloak and fastened it around Phrygios’ shoulders, clasping it with a gold brooch. He put the eye patch on him and fastened sword-belt and pouch around his waist. Looking at the dying man, he had an eerie feeling, as if his soul had escaped and was looking down at his own body. He shook his head and scanned the garden.

The Romans would be here soon. Impatient of their quarry, they’d break down the door and attack in force.

Chylon hauled himself painfully up an olive tree. It was hard with a leg that throbbed and bled. When he’d gotten near the roof, he put his weight on a branch. It creaked, lowered, bent, just enough so he could take another step and hurl himself onto a ledge. Exhausted now, he sank down, chest heaving, just as the Romans came into the garden.

He lay still on his side, not daring to move for fear of triggering their peripheral vision. There were four men with shortswords. They swept into the garden in a well-drilled formation. The sight of the one he’d killed with the sling didn’t disturb their search. One of them noticed Phrygios’s body, and they flowed toward the back wall. They prodded him with their sword, then turned him over.

“Dead,” said one. “But how?”

“Maybe Zeus took him.”

“Spare us your swaddling stories. Are you sure it’s him? He doesn’t look like much.”

A slim hooded figure in gray walked across the garden and joined them.

“It is him. I would know. He was my lover, after all.”

Chylon almost gasped at the familiar voice. Rhene.

“You bedded this worn-out butcher, eh? Well, a whore doesn’t get to choose, does she?”

“No,” came her voice sadly. “She doesn’t get to choose.”

There was a metallic clink as one of the Romans tossed a pouch at her. She caught it and tucked it under her cloak. Chylon stared, teeth ground together, lips pulling back from his teeth in pain.

“You didn’t help much, whore,” said the Roman. “We lost four good men.”

Rhene watched as one of the assassins chopped off Phrygios’s head. Then they departed for the house. Rhene followed slowly and gracefully. Something caught her attention—she looked at the olive tree Chylon had climbed—her gaze climbed half-way up and then stopped.

“Whore,” called one of the Romans. “Are you coming back to the tavern? I think we’ve earned a little extra for tonight.”

“Yes. I’m coming back.” She paused, still. Her voice came low but distinct through the soft rain. “They threatened to kill my father, other townspeople. I am sorry…”

She followed them into the house.

“When Hannibal was informed that the king’s soldiers were in the vestibule, he tried to escape through a postern gate which afforded the most secret means of exit. He found that this too was closely watched and that guards were posted all round the place. Finally he called for the poison which he had long kept in readiness for such an emergency. “Let us,” he said, “relieve the Romans from the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man’s death.”

Livy, The History of Rome, Book 39

________________________________________

Michael W. Cho lives in Tempe, Arizona, where he plays Spanish guitar for his day job. He has publications in Terraform and Daily Science Fiction, among others. In his work, Michael focuses on bleeding-edge topics such as politics, futurism, and flesh-eating monsters. He began writing in his pre-teens as way to process losing his D&D group, and despite often turning down the Call to Adventure in later years, often finds himself returning to the Journey.

Robert Zoltan is a Los Angeles-based author of literary and speculative fiction. His previous Rogues of Merth story, The Blue Lamp, appeared in Heroic Fantasy Quarterly #26. Further adventures of Dareon and Blue can be found in Rogues of Merth, Book 1, available at Amazon. His illustration appeared on the cover for The Best of Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, Volume 2, and his work will also be featured on the cover of Volume 3. Robert is also an award-winning songwriter, composer and music producer, audiobook drama producer, voice actor, and host of Literary Wonder & Adventure Show podcast, which can be heard at http://dreamtowermedia.com/podcast/.