FIVE DAYS TO DRAGONHAUL

FIVE DAYS TO DRAGONHAUL, by Evan Marcroft, art by Miguel Santos, Audio by Karen Bovenmyer

The day before I was to begin my journey north, I rode the train down to the Needles Quarter to purchase new winter boots. I quickly found two ideal pairs at a canopied stall operated by a harried widow. They were identical–both of cobbled thrunx leather insulated with arctic bear fur–save for the price: one was cheaper by some ten doubloons. When I asked the reason why, the stallkeep replied impatiently that one was flayed off the arse of a hunted animal nearly one thousand leagues from here, while the other had been cultured in a vat here in the city of Sabot out of low-quality krut over a span of twenty days. She then barked at me to pick one or move along, and I of course chose the zooefacted product.

I do not know why, weeks later, with my mission done and behind me, I finger this moment out of all others on the string. It was not a crossroads of any sort. The path had been chosen well before I set out along it.

###

As soon as my companion and I stepped out of the train I was smothered by a desert-like cold, the subcontinent of Thoreal telling me with no maundering that it did not want me here. Like all those who still lived in this lonely place, I did not listen. Like all those, for better or worse.

The debt I sought was here somewhere, in someone’s pockets.

It was called the Kleigh, and it was the train’s final stop. Rails that bound a continent together ended here in a heap of loose gravel. A strip of land like an icy crust between the sheer Survivors mountains and Yeghul’s Bay, the Kleigh had served as a border outpost in those days when this land was ruled by stone-jawed Viskarl kings. These days it was a refuge for trappers, scavengers, miners, and fishermen, a place that had fought long for permanence and was slowly losing. Half-town, half-camp, driftwood shacks intermingled with frost-shingled log cabins and seal-hide tipis. Those that came here sought plunder and little else, and there had never been enough to make them stay. The waters here were once wormy with arctic hailong, and their leviathan bones were ingrained in the town’s architecture. But with increasing frequency, the brave men that went out looking for them came back with bloodless harpoons.

At mid-day the Kleigh was as bustling as it would ever get. Teams of hunters lugged mounds of pelts so fresh that they yet bled down their shoulders. Sled dogs quarreled over bones in the street. Wives peeled vegetables and chopped wood, and windburnt whores beckoned unenthusiastically to me from the shelter of their doorways. Survival superseded all in the winterbound wilds of Thoreal, dignity most easily.

I ignored everything offered and made my way expediently towards the tallest plume of chimney smoke in sight, which tapered downwards towards a trappers’ saloon and inn called The Pitfall. There I inquired as to whether any could tell me the whereabouts of a hautloft called the Zaubermanck or, more preferably, its captain. At the firm urging of my larger partner, I was directed to a landing field on the southwest outskirts of town.

I spotted the Zaubermanck immediately, for it was the only hautloft currently docked there. The zooefacted air vessel–half-flesh half-artifice–had seen better days.

Its captain was a pair of legs protruding from under its keel. The rest of him came wriggling out onto his haunches at the sound of my approach. He was small but broad-shouldered, the hard core you get when you whittle all the weakness off a man. Not wrinkled by age but corrugated. A face built around a chisel of a nose and a club of a jaw. One oil-stained hand scratched ice out of his whiskers; the other leveled a battered Kraumtausser brand revolver at my chest.

His small, black eyes moved from me to my companion, in whose shadow I stood. I may have been intimidated, but the autovault did not have that capacity. The eight-foot tall, steel-jacketed chimera stared back at him with a face of featureless armor until he was forced to blink.

“Miwhale Souht?” I asked. “The sky hauler?”

“Who the hell are you?” he demanded in reply.

I offered a bow. “My name is Etlin Jaud,” I replied. “I am a debt collector with the Huigshauter Collateral Recovery Agency. I can provide my license if you wish.”

The man said nothing, so I continued. “I must notify you that the debt you previously owed to the First Tolbewan Bank of Blessings has been purchased by the Haethrn Delinquency Company. The new owner of your debt has elected to collect in full without delay. So, I am here.”

From the breast of my leather jacket I produced both my business card and Letters of Evidence demonstrating the lawfulness of my presence as well as the amount to be repaid. Miwhale Souht read them twice over and then balled them up in his fist.

Incredulously, he growled, “You legged it all the way up to the frostbit limb of Supborhailles to shake me down for a few drowning doubloons?”

“I am a professional,” I said, diplomatically. “And I should say that it is a fair sight more than a few doubloons. Please lower your weapon, by the way. My companion is growing agitated.”

As if cued, the autovault dispensed a wet rumble from somewhere its innards. A standard issue collateral transport and bodyguard, it had been bioengineered solely to defend me, or any value stored inside of it, and it was strong enough to crush a thief against the inches-thick vault door in its chest.

Miwhale reluctantly holstered his pistol. “Well you’re on the mark there, lad,” he muttered. “And I’ll tell you what, I ain’t got a penny of it. Couldn’t even pay to send your arse back the Sabot way.”

“I am prepared to accept repayment in other forms,” I said. I take an appraising look at his air ship. “Everything has its value.”

Miwhale let out a coughing guffaw. “Hah! That there’s a breakening-up tub of rust and piss.”

“True,” I admitted. “But it would be a not insignificant chunk of your debt.”

He spread his hands helplessly. “Fucys send me from fools. And how d’you expect me to collect the rest without a ship?”

Before I could answer he silenced me with a finger. “Listen you,” he said. “I’ve got the solution to your problem and mine. All I need is five days. Alright? Give me that, and you can have my ship, if you’ll still want it.”

I cocked my head. “Speak then.”

A gray tongue wet blistered lips. “Dragonhaul,” he said, like a wolf remarking on lambs. He stood and pointed to the North. “Came down yesterday morning. Felt it hit all the way down here. That means its big as a mother. You know anything about dragons, lad? You know what they’re worth? I do. I spent my whole life waiting for one. You can’t zooefact them. The technology ain’t that good yet. And every part o’ them’s good for something–better than anything else.

“We get to that dead beast and fill up my ship with as much as will fit. Blood, bone, eyes, brain, piss! One trip’ll make me rich as a Quartermaster, and that makes everyone happy, don’t it?” His eyes gleamed with greed. “I’ll pay ‘em back double. What say you?”

I did not answer immediately. This was an atypical situation. But, not unheard of.

“Very well,” I said. “But on the condition that I accompany you. It is my duty to secure payment to the best of my ability. Is that agreeable? I assure you that I am highly capable.”

Miwhale’s brow clenched in suspicion, and I keenly felt myself appraised. I sensed that he was shrewder than his Screwalt brogue implied. “Highly capable of paining my arse,” he eventually groused, and gave me his paw to shake.

With terms decided upon I returned to The Pitfall to seek lodgings for the night. We were to shove off tomorrow, at the first thread of light. There, a dark-eyed youth emerged from an alley to try and sell me a gun he would not let me see. I would need one around here, he wheedled. ‘S dangerous, you ken? I turned him down courteously and showed him that I had one already, which sent him and his hidden friend running off.

###

We know little of the near universe just outside our mouselike planet and its thin envelope of atmosphere. What ecologies exist are as opaque to us as those of the aphotic pressure of the deep oceans. But we know they exist, and that dragons are not an apex predator. The intellect cowers at what might have killed such a creature, but something did. There was a bloody grappling in the trench between the world and its moons, and it lost. Dead or dying, its body must have been yanked from the jaws of its killer by the littlest finger of our world’s gravity.

Its fall would have been a relative apocalypse. The parasites clinging dumbly to its squamous hide would have been incinerated as their host splashed through the atmosphere. The dragon must have seemed a downed star, flaming in undiscovered colors as its vacuum-proofed epidermis reacted with nitrogen and oxygen in a chemical rapture. And if, by some cruel miracle, it had survived that descent, burning all the while, the impact would have killed it and absolutely everything within its blast radius. Dashed against the tundra, it would have thrown meaty particulate across leagues—I pictured winterbound camps swamped in molten flesh–and raised a plume of dust and steam visible behind the curvature of the planet.

Many who saw it fall would call it an omen, something god-lobbed. But a few would know it for what it was: money. A centennial opportunity to get flush. A treasure-corpse put on ice and just waiting for an enterprising someone to come and dig out its solid gold heart.

Five days from here was your dream come true.

###

I was relieved the following morning to find Miwhale waiting for me and chewing an obnoxious cud of fermented leaves. Wordlessly he hooked a thumb over his shoulder, inviting me into the hanging belly of his ship. I had half-expected the man to run off without me in the dead of night. I wanted to think he was an honorable sort, but he simply could have known I’d chase him. And so, as the morning began to hatch, we lifted off and set out with no fuss.

I was acquainted right away with the Zaubermanck’s meager crew. Miwhale himself was primarily the navigator and mechanic, knowing best how to keep his hautloft airborne, while Nihoi, a scarified man missing the tip of one ear, served as its helmsman and stormreader. Being Pteyrouni, a tropical race, he wore layers of furs to combat the cold. The ship’s defense took the form of Nunijh, a muscular, taciturn woman bearing the blackened forearms of a Tarfellow gang member. Both were Sabotine born and exiled, but Miwhale seemed to trust them nonetheless. I eked no more than a few curt words of greeting from the two of them, which offended me not at all.

My living space was a spare hammock in the cabin, with a stack of threadbare pelts and my own unwashed clothes for warmth. None of the others were any better hosted. It was far from the worst foxhole I’d ever had to hide in, however.

With nothing to contribute besides the dead weight of the autovault, I spent much of the day at a porthole watching the land rise and fall. These were not the mountains of my homeland. The Hornpile Mountains west of the city-state of Sabot were jagged and jutting, offering safe trails only to those with the stones to look for them. The Gill Range to the South was verdant and warm, reclining on the sand with its toes in the water. These peaks, however, were dizzyingly tall and steep, worn smooth by blowing millennia, and as frigid as a watery grave. I understood why the locals had dubbed them the Survivors. Their icy coats preserved bones and ruins. None who had lived among them still did.

Towards sundown Miwhale came to inform me that we would be landing soon. “Last spot of civilization till ever’s there at the foot of Big Chimney,” he said, pointing towards the last and tallest peak in the range. “Little mining town called Crumb. We dig in there for the night, fill up us the boat, and hope it’ll do us done.” He prodded me with a challenging look. “Last chance to cut out.”

“Thank you,” I replied graciously. “But you won’t be rid of me so easily.”

As soon as we touched down on the outskirts of Crumb and set the Zaubermanck up with a trough of krut to sip from with its mothlike tongue, Miwhale set off for the saloon, which was the largest structure in the meager town after the administration building and infirmary. I followed, at a distance.

The air here at Crumb was prickly with the thaumaturgic wrinkles in physics that in Sabot were called nicks, owing to its primary industry. The stormstone they dug out of the mountains here was infused with nethic energies, and you couldn’t handle it safely enough to not leave charcoal smudges on the laws of reality. The worst I saw was a water pump endlessly spigotting out more of itself. They’d put up a little fence so no-one would touch. Half the men I observed at the No-One’s Favorite cantina wore the stain of their labor openly. Shirtless backs resembled crumpled first drafts of people. Nicked miners sloshed beer through inverted mouths.

I watched from the corner behind the fire as Miwhale capered among them like a one-legged man at a no-legged ball. He drank through four jars of the moonshine they brewed out of rattleweed, and once his brain was floating free in it, he ordered shots for anyone who asked, spilling more coin behind the bar than he’d sworn to me he had. The size of his debt no longer seemed so inexplicable.

He drank, and he sang, and he fought, and it didn’t matter to him who with. He would kiss a man’s whore and then knock him flat, then lift him up and offer him a free gulp of choop. Kiss him too, why not. The little man owned the room and everyone in it, like the biggest of the children in the schoolyard dictating to the rest what fun they were going to have next. My judgment of him was that he was loud, and crude, and loving, and brave, and conniving. A sorry friend and a wonderful enemy. Some might have described him as larger than life. But a story is shaped by the story teller. Those qualities did not matter at all to me.

I only cared for what he owed.

###

We were eight hours into the second day before we spotted trouble riding our shadow.

Nunijh, who was manning the binoculars, gave a shout that brought Miwhale and I running. “Pursuers,” she said tersely, pointing at the mole growing malignant on the near horizon. Miwhale took the binoculars and glared into them.

“Bastard, him,” he muttered, by way of explanation. Someone from Crumb, possibly. A rival sky-hauler after the lion’s share of the ‘haul. Perhaps someone who’d simply taken one of his mean jokes the worst way. Who knew? Miwhale didn’t think to share.

It was a fight, albeit the slowest one I’d ever been in. The Zaubermanck was moving at top speed but the other ship was the stronger one and gained on us steadily. Around suppertime they began to fire upon us. For some twenty minutes we endured a steady rainfall of living harpoons, the sort designed to gnaw through hailong scales and swim through their blubber. They worked nearly as well on a steel hull, as we discovered when one at last found its mark and began boring towards the hautloft’s engine. I beat Miwhale in a race there and found the thing nearly through. “Kill it!” he hollered, and my eyes fell on the spade propped up by the door; a few hard strikes split it into wriggling halves.

We returned to the deck in time to flinch as Nunijh shot a mortar round high into the air. Seconds later the air around the pursuing vessel was engulfed in a gunmetal smoke. Two more cannisters, and the ship began to flag as screw-nosed nematodes ate away at its organic flight-sacs. We watched the lazy crash progress until the receding taiga took it out of sight. “Better be the only one, ‘cause that’s all we got o’ that,” Miwhale grumbled bitterly. “Thirty-four doubloons a shot. Bugger me gentler, all you gods listening.”

I understood that I had just born witness to many deaths, but I couldn’t fault the crew of the Zaubermanck for defending themselves with no other choice. The law extends exactly as far as a policeman cares to walk; up here, they would lose toes and ears trying

Miwhale decided to land as soon as possible, in the first patch of clear land among the increasingly sparse evergreen forest below. It was foolishness to press on with the Zaubermanck having open wound, and we were losing the light anyway. Better to bunker down for the night.

It was pitch black by the time repairs were finished. We took watches in pairs, and I found myself sharing one with Miwhale. We sat on deck about a drumfire that burned nearly lightless. To pass the time and help us forget the cold, Miwhale shared stories and tall tales. This land was wolf land, tamable but unknowable. It bred fearsome critters as quick as rats, and he knew them all. There was the yallallyhoo, the bird that cooked itself but could sound like any other bird. I ought to look out for snow gulpers, which looked like ordinary snowbanks until you traipsed into their cave of teeth. And most of all beware the uhughul, the giants that trapped men for their hides, and took the souls of great caribou for their steeds. I asked which of them were real and he said every last one, in shades.

And when he grew weary of stories he asked truth in return. “You come from Sabot, aye? I ain’t been back there in a pack of years. What’s the news? Who’s the Quartermaster now?”

I shrugged. “Still Brugan Staymer.”

“Should’ve guessed. That great, mean bastard.”

“Mm. Maybe not for long though,” I said. “There’s a revolt on. Staymer the younger wants her father’s job, and the Commonfolk have found the stones to get behind her.” In fact, I had initially believed that was why my client had called Miwhale’s debt. In times of political upheaval, cash in one’s hand was worth more than cash in someone else’s.

But I suspected he had a reason more personal as well.

Miwhale snorted at that. “Lutnae Staymer, that wee girl? Nah.”

I peeled open a tin of beans and held it over the fire to warm it up some. “She’s twenty now.”

That seemed to electrocute him. “Oh,” Miwhale sighed. He slumped back against the railing, as if suddenly too heavy for himself. “Time’s queer up here, you know,” he said, looking askance into the whistling dark. “Go out, dig up something, come back, sell it, make enough to go out again. And it’s always the same damned snow. Same damned sky.”

He sat like that, in distracted silence, as I told him of the terrorist attack on the isle of Old Morso, the progression of the war with the Cmem Empire in the south. The songstress Stella Lugbazzi was touring the opera houses of Mongerslea Isle and Leukgengkrom. A new Tuyorni church had gone up in Gospel Fen to replace the famous one that burned down. I ate and talked. I could not tell if he recognized any of what I described, or if to him I, too, were inventing critters from nothing.

A bird made a sound off in the distance. Yallallyhoo, I thought, but probably not.

“That was quick work you did back there,” Miwhale remarked, a while later. “You military?”

I chewed, swallowed. “Hussariat. Seventh Precinct.”

“Ah, a policeman then.” he said. “Thanks for your service, mister black-coat.”

“It’s nothing.”

His expression turned wary. “Were you hot, or cold?”

“Cold,” I replied.

“Ah.”

He spoke no more after that. I think that he was no longer sure of whom he was speaking to. The difference a word can make, I supposed. The difference between doing a job in the day or the night.

###

Miwhale’s mood turned sour the third day. The dragonhaul was paradoxically too immense a hoard to possibly split with another crew. He began to spend more time on deck, glaring at the horizon, fearing almost to the point of hoping that another rival would come slinking over it.

Throughout the day we followed a river whose lips were well-shaven of foliage. Among the trees below I would now and then spot the occasional right-angled carcass of a logging camp, long deserted. Tree-clearing machines lay abandoned under rust and moss and frost like weapons thrown down in a route. Cleared patches of forest were scabbing over with green again. The people of Thoreal had dried up as the need for its meat did. Nearly everything it had to offer could be grown from template in a damp basement in Sabot. We were flying over the high-water mark of man’s interest in this part of the world. Our ancestors had fled here two thousand years ago, and here we were fleeing again, escaping cost inefficiency. I doubted that this time we would ever come back.

“Remember when this was all its own country,” Miwhale muttered. I was not sure at first if it was meant for me, but I was standing nearby. “Twenty years behind, you could make an alright living running pelts and things between here and the Kleigh. From there they’d go everywhere. They paid big for natural fur, them fancy ladies down on Mongerslea Isle. Not no more though. Now they know there’s no difference between real and something squeezed out of a vat but the cost.”

He bared his yellow teeth in a grin that was not a smile. He shook the railing as if yah-ing on a racehorse. “Dragon still good though.”

Miwhale Souht had never been shy about his avarice. But this was the first I’d seen of a softer, bloodier desperation beneath it. Out of curiosity I asked, “What will you do with your profits off it?”

He repaid me a venomous glance and spat into open air. “Pay you the price you name to screw yourself, you lamprey.”

We both started at a sharp yelp of pain from below deck. Not a sound one could ignore twenty fathoms in the air. Being the younger man, I beat him to the source. Down in the hold I found Nihoi collapsed against a krut-tank clutching his bloodsoaked hand, while Nunijh danced around the autovault with a knife. My autovault remained stoic but with a tautness in its shoulders that I knew to mean agitation. I inserted myself between the two before the autovault could lash out and take the woman’s head off.

“Your fucking monster broke my damned hand,” Nihoi snarled.

“Then you must have been trying to access its locker,” I said.

“So what if I was?” he retorted. “We got a right to know what’s on this ship. Am I right?”

Nunijh grunted her affirmative. She was a miser with her words, but I sensed a greater bond between the two of them than either with Miwhale. I hadn’t missed how they shared a cabin.

“Your ship,” I said carefully, “belongs by law to my employer. Technically, you are guests.”

Nihoi cocked an eyebrow. “Oh aye? And just who hired you, anyhow? I’ve been meaning to inquire.”

I briefly considered answering forthrightly, but erred in favor of discretion. I was a professional, with high expectations to meet. “I have been contracted by the Haethrn Delinquency Company.”

Nihoi lurched away from the wall and shoved past Nunijh to stand within a finger’s length of me. “Save that shit to feed to the real fools,” he sneered. “’Just a business’ only cares about profit. You can’t tell me they honestly think that Miwhale’s debt is worth the expense. Ain’t no fuckin committee fool enough to shell out to send you and your pally there to shake us down for fucking pocket lint. There’s a man, ain’t there? Someone with a score to settle. So what’s their name, huh? What are they really after?”

“I am a professional, sir, and that information is confidential.”

“Stow it, the lot of you,” Miwhale barked. He grabbed us roughly by the shoulders and pried us apart. “You drowned idiots think this is the time to have it out? Might as well steer us into the trees and call it an early day. Supposing you all want to see tomorrow, we can’t be turning on each-other, ‘cause we’re all we got out here. Every problem is everyone’s problem, and when we got a problem we got to make it right. You ken?”

His was the tone a father might take with a pair of bickering sons. But I could see his point, and so did Nihoi by the way he looked at his feet. Even in this far-flung place, where the world seemed to run thin on ideas, the only things we had to put between ourselves and death was one another. I gestured at Nihoi’s wounded limb. “Your hand should be fine,” I said. “It’s your finger that’s broken, by the look of it. If you’ll allow me, I have the relevant experience.”

“I can splint it my own self,” he said, but I saw him consider it first. I supposed that was better than nothing. Nunijh sheathed her knife and walked away with Nihoi; the autovault lowered its hackles and resumed neutral attitude. Miwhale looked at me like he still had some yelling in him, but took his own advice and stomped away with a bullish snort.

Nothing further troubled us that day, but Miwhale and the others tackled the swarming chores of maintaining a ship with skin clenched as though at any moment it might. Arising from the distance like an inverse mountain was a great anvil cloud of dirty red, proof that the dragon really was there, rotting but dead-gravid with promise.

###

Around noon the next day, according to the angle of the sun, there came a startled bellow from Miwhale down in the engine room. Nunijh beat me there, and I had to crane over her shoulder to see what was the matter. Miwhale, kneeling, held up the cnidolantern he was seeing by. A smattering of eyes in different sizes had pimpled up of its tin casing. They spun wildly, as if transmitting terrifying imagery to a nonexistent brain.

It was determined that this was a matter for Nihoi, who had the proper training, having once been a stormreader for the Sabotine navy before his dishonorable discharge. Leaving Nunijh to nanny the ship’s controls, Nihoi consulted a rusted nethestrometer that spun out a pig-tailing tape of incomprehensible readings. Troubled by what they told him, he clambered onto the deck and performed a minor nethic ritual with the cord of tiny skulls he wore around his wrist, which made the light around him go coarse for a few seconds. Nodding, he turned back to us to vindicate our fears. “Aye, it’s a nethersquall,” he said resignedly. “Might’ve been the dragonhaul what stirred it up. We’re lucky to catch it this far ahead of time, at least.”

“Can we outrun it?” Miwhale asked.

Nihoi blew steam out his nostrils. “That is up to the storm, I think. I’m sorry.”

Miwhale seemed to take that as a challenge and told him to whip the ship like an ass if it would make it move faster. We carried on like that for several hours before it became clear it was useless. The storm was nothing visible; not so much a phenomenon as a circular saw slicing through the established structure of the universe. An alive but mindless un-logic hunting by sound and feel, blindly clawing holes in everything it touched. I saw a flock of leering punchdaws wing into existence alongside the Zaubermanck, only to snap-freeze into pearl figurines and plummet out of sight. Clouds appeared and disappeared at random. Disembodied surfaces intercepted shadows cast by nothing. Looking for a logic in any of that was time better spent penning one’s last will.

When one of the ship’s lower flight-sacs burst as all the gasses inside spontaneously ignited, even Miwhale had to bow to the mounting risk, and so he ordered Nihoi to take us down. We had only luck to protect us, but luck was slightly better closer to the ground.

###

“Come on then,” Miwhale barked from the doorway, motioning me over. I’d just finished feeding the autovault, so I nodded and followed him out onto the ground.

As Nunijh fed the ship and Nihoi kept watch over his nethic-sensing instruments, Miwhale had prowled anxiously about the Zaubermanck, as though every minute we spent idle was another mile the dragon crawled away from us. It was getting dark now though, and we would need materials for a fire if we didn’t want to burn what we might need in an emergency, so that gave the two of us something useful to do.

Landing on the taiga seemed to displace the rest of the world away from us. Down here, all one could see in any direction was snow and dead trees and shrubs too hardy for winter to kill. But there was nothing doing until the squall moved on. Nightfall at least made it easier to forget how far we were from where we were going, how even further we were from home.

Miwhale and I set about gathering branches and undergrowth for kindling. It was uncomfortable work, having to stoop and fight frozen dirt, and soon we couldn’t see past the radius of our malnourished cnidolanterns. Miwhale offered nothing in the way of conversation to make the chore go faster.

“What’s the plan when we get to the dragonhaul?” I finally asked.

Miwhale grunted as he bent to haul on a particularly sessile weed. “Thinking brain first.”

“Oh?”

“Aye. Brain’s the most valuable part,” he said. “Them sorcerers on Cold Qualm use it for unholy things, and they’ll buy it by the ounce. From what you hear of dragons, I figure we take the whole brain with some cargo space leftover for lymph and eyes. They don’t go bad quick, dragons—ain’t the same animal stuff as us–so no worries there. Five days back and we’ll be sleeping on doubloons.”

He tromped back to the oil drum we’d left by the ship’s boarding ramp and hurled his forage in with the rest. “Five days back, sell it off, pay you off, and head back out for more. That’s the plan.”

“You’ll be coming back?”

Miwhale spared a sooty laugh at that. “What, you thought that’d be enough? I can’t take it all, man.” He conjured a flask from deep in his layers and helped himself to a swig. “Fucys send me. Ain’t no such thing as enough.”

I thought that might be the end of that, but to my surprise he kept talking. “I got a boy, you know. Back in Sabot.”

I was well aware of that, but I nodded along.

He took a second, longer gulp. “Little Karal,” Miwhale said. “You’ll never meet a better a kid. Real smart, like I ain’t. Fat as a keg though. Got that from his mother. Luto help me, but she was a bloated cunt. Oh sure, she was happy to ride the horse, but she didn’t want to buy it. She said I weren’t worth nothing keeping around, on account of how I’m a lush and that. I said I was the boy’s father and I had a right to be, and she said you planted a seed, fine, but a father takes care of his family, and I didn’t have more than three pennies to my name and only then ‘cause you can’t get drunk on that. So I said fine, bitch, and I came up here to make some drowned money. Said to her, you just let me know when I’ve paid my bill. So that was two mistakes I made, right there.

“First was making deals with that witch. Sure, she’d let me see him when I could make it down Sabot way. So long as I was sending her cash, at least. And even then, never for long. And I could never stay long anyhow, ‘cause every minute I was there I was letting money get away up here.”

He broke off to empty his flask in three long swallows. “Second was thinking there was money in this drowned place to begin with.”

The bioluminescence of his lantern flushed out all the hidden lines of his face. He looked ten years older in that algae green glow. “Everything costs something,” he muttered. “It costs something to get your ship from one point to another. Your crew’s got to have their cut. Something breaks, and that’s gonna cost a lot. Some fool shoots at you, it’ll cost to kill him. The man who takes money back to your son is gonna take his share and it’s never what he says it is. I’ll tell you what—I’ve made my fortune ten times over and it all wound up in someone else’s pocket.” He glared down at his nose at the flask in his hand, but he didn’t let go of it. “All I ever kept was enough to go back out again. And every time, there’s less to bring back.”

“I think that’s life,” I offered.

Miwhale chuckled darkly. “Who’re you to tell me that? You’re another drowned hand reaching out for its cut of my profit. You’re a lamprey, is what you are.”

He fixed me with a poisonous look, and it seemed that there might be a fight.

Then he sighed, and the moment blew away.

“I know that’s life,” Miwhale said. “Life ain’t nothing.”

“Get your gun out,” I said. “Something’s coming.”

I shone my light in that direction and washed the dark off the shape that came towards us like dirt from a fossil. It was an ice bear, nearly a fathom at the shoulder, approaching unhurriedly and with a staggering gate. Its pelt was threadbare and hung loosely from the rack of its spine. Its wide, flat head hung utterly limp, even as the rest of it plodded lethargically onward.

Miwhale flicked the safety off his weapon but did not shoot. “Looks sick,” he said.

I unholstered my own Gesserm-Fossarm and plugged it through the top of its skull. The bear flinched as if bug-bit and kept walking.

“That’s not it,” I said. “There’s something else-”

Then, too late, I became aware of the two wide, mad eyes staring at me from either of its shoulders.

As if knowing it was discovered, the bear reared onto its hind legs with an energy it did not have before, tossing its limp neck over its back. Two arcs of shark’s teeth stretched apart the rent chewed out of its belly and let out a yowl that stank like butchery.

It was only luck I was not killed then, when a flint-tipped spear scraped through the meat of my cheek.

I let the force of it throw me to the ground, and heard more spears whisking through the air. I saw Miwhale, knowing the beast for what it was now, empty his gun into its ribcage where its motivating ganglia were hidden. As it toppled backwards I flung my cnidolantern into the murk beyond it, and that cartwheeling light betrayed at least three more man-eaters barreling towards us.

While Miwhale reloaded, bellowing for his crew, I spent my remaining five shots as wisely as I could, catching one anthrophagus in brain outright, winging another in the leg and bringing it down. The last ghosted through two bullets and made it into Miwhale’s light. Robed in furs as it was I might have still mistook it for a living human, were it not for the vestigial head lolling this way and that. I pitied whomever had gone that long unaware of the parasite gestating in their liver. The pain of it eating its way towards its first breath would be the last thing he felt before its tail strangled his spinal cord dead.

I waited until the last possible moment and fired only when I could not possibly miss. My last bullet slipped between its stolen ribs and killed it before it came out the other side. But before it even hit the ground I heard more bounding of them through the snow.

I stuck two fingers in my mouth and let out a coded whistle. There was a thundering from the bowels of the Zaubermanck, and the autovault came stampeding out. The oncoming anthrophagi veered away, drawn by instinct towards this larger, louder target. The two sides collided and only the autovault kept going, with pulverized flesh pasted across its body. Half a dozen survivors, mangled but fueled by a berserk unintelligence, fell upon it as one furious mass, but the autovault’s organic components were few and their stone and bone weapons could only scratch its plating. Conversely, the autovault’s strength turned its fists into limb-cutting blades. Its every motion smeared flesh between the grinding surfaces of its body. it was less a fight than a pity.

I caught Miwhale looking at me as though it were I with gore unspooled between my hands.

Only in the relative silence of the massacre did I register gunshots from the other side of the ship. Miwhale and I bolted upright and ran for the rear of the Zaubermanck. There, we stumbled into the middle of a shootout between Nihoi and Nunijh and a second party of anthrophagi.

The monsters came at us unorganized and unafraid to die. The four of us stayed steely and spent our bullets like investors buying stock. Fiery belches blew holes in the night and flesh alike. The snow was soon cankerous with at least a dozen of the monsters; the survivors hung back, their ganglionic hindbrains perhaps finally sensing futility. For a moment it seemed we’d won.

Then from the occluded tree-line issued a deafening crack of splintering timber. The dark grew a tumor, one that sprouted columnal legs and mountainous shoulders. Nothing less than a gargantuan polar mammoth lumbered towards the Zaubermanck, the four tusks on its great, slack head plowing furrows in the snow. Someone’s gun barked and a red pinprick appeared in its shoulder. The beast reeled blindly towards the sound, exposing the dozens of puppeteering mouths that had bored outwards through its pendulous gut. I had never heard of an anthrophagi infestation so severe, but then this was where the world hid its remaining secrets.

“Get on the ship,” Miwhale said breathlessly.

That was all the argument he needed to make. I was last aboard the ship’s boarding ramp and was barely inside before Miwhale threw the lever that slammed it shut. We hurried to the deck, pausing only to grab a box of ammunition and the blunderbuss from above Miwhale’s cot. No sooner had we stepped outside was the Zaubermanck rocked by a sudden impact. We ran to the railing in time to see the elephantine anthrophagi stomp backwards and prepare to charge again. Lesser maneaters capered around its rime-crusted ankles like the frenzied worshippers of some primeval god, many more now than we’d left dead on the ground.

I placed my remaining shots well, but there were more of them than I estimated we had bullets. The autovault was fighting valiantly on the ground, but I could see it beginning to flounder under the weight of so much gore. Miwhale let loose with his blunderbuss, popping hunks of skull and scapula out of the mammoth yet troubling it less than a hornet. Anthrophagi began to scale its haunches, hoping to use it as a grisly siege tower.

“What do we do?” Nunijh hollered at her captain. Miwhale ignored her and continued to shoot; I suppose that was his most efficient answer. If his brain was no use here, mine would have to do. We’d soon be overrun, supposing the mammoth didn’t tear the ship down first. I spared a few thoughts to take census of all tools at hand–anything was a weapon in desperate circumstances. It was hard to concentrate with the autovault indisposed. With it preoccupied, I had to worry about the crew as well as the anthrophagi; if they wanted me gone, this would be the right moment.

I forced myself to stow those unhelpful thoughts; Miwhale’s crew were tools at hand themselves, and there were more imminent threats.

“Nihoi,” I said, seizing the man’s attention by the shoulder. “Where’s your nethestrometer now?”

He sneered at me, uncomprehending and distrustful besides. “The fuck does that matter?”

I pointed my gun at the sky. “The storm is still blowing, isn’t it?”

His eyes shot wide as he saw my plan.

It was not a matter of trust, but survival. I held off the anthrophagi with a gun in either hand until Nihoi hastened back to the deck lugging the cumbersome instrument under his arm. A device meant to study the ebb and flow of the Nethestrom, it contained a tiny chip of stormstone in its core. A nethic expert such as Nihoi could conceivably use that latent power in concert with the agitated nethersquall overhead to do terrifying things.

It was a risk–the Nethestrom could not be commanded, merely steered at best–but unlike the anthrophagi, it was not a guarantee.

We fought for every second it took for Nihoi to crack open his machine with a prybar and begin, with raw-throated chants, to work his arcane science. Anthrophagi clambered over the railing all around the ship and we beat them back as best we could with the butts of our weapons, with their own primitive javelins, with our very fists. Blood arced and froze itself fast to the ship in jags and curls. The monsters paid no heed as the wind began to spiral against itself, as the sockets that held our selves snug within the machinery of the universe began nauseatingly to loosen. Two inevitabilities were closing swiftly towards each other and crushing us between them.

“Down!” I heard Nihoi bawl at last.

I did not dare look back, but I could feel strange energies rushing past me as though some vast thing just beneath the surface of this reality were breathing in, preparing to shout. I let Nihoi’s command flow from ear to nerve without passing through the brain and hit the deck face-first.

An explosion I’d expected and did not get. In fact there was very suddenly no sound at all, save for the heavy drag of blood through my ears.

I stood warily, the silence somehow more alarming than shrieking man-eaters. A perfect circle of blue daylight had been punched out of an otherwise infinite night. I crept to the railing to survey the aftermath of whatever Nihoi had made happen. The mummified corpses of anthrophagi were strewn across the glistening snow below. The mammoth was a brown lump like a fruit pit spat out by a giant. It was as though time had braided itself into tentacular centuries and whipped them to death. I doubted Nihoi had intended that, or done anything more complex than beg in the right language. Our microscopic intellects could only grasp the Nethestrom’s mechanics the way an ant could apprehend high mathematics.

“All clear,” I announced, and it was at that moment that Nunijh chose to scream.

###

It wasn’t a spear that had got her, in the end. When Nihoi got the Nethestrom riled up it must have lashed out, blind and dumb, and nicked her. A long, pearly-clean bone now sprouted perfectly perpendicular from her thigh and emerged out the other side several inches higher. There was no blood. When Nihoi touched it, it trembled like one impossibly contiguous length.

“This is your fault,” Nihoi seethed, cooking me with the hate in his eyes.

“I don’t see how,” I said truthfully. “We’re alive. Isn’t that the greater priority?”

The other man looked ready to lunge for my neck, until Nunijh’s hand found his and gripped it tight. That seemed to quench the fire in him. He sighed and turned back to her, brushing the hair from her fluttering eyes and whispering solaces into her ear.

“She won’t bleed out if we’re not fools,” I observed. “But there’s nothing doing for her here. We put her in bed until we’re back home, and that’s it.”

Miwhale, who had said nothing thus far, nodded distractedly and helped Nihoi carry Nunijh inside. It did not need to be said we would not turn back for her sake. At this point we’d come too far. As a small consolation he lent her the furs off his hammock, as well as one of the bottles of rum from which he filled his flask. I meanwhile took the time to drag the dead anthrophagi away from the ship, leaving them as a sort of peace offering to the next predator to come along.

We remaining three took up a patrol about the ship until the sun came up in the rest of the sky. The autovault stood under the bow like an amputated figurehead, twitching its head at every small sound. In the gray morning I helped it wash off its caked-on blood with handfuls of snow.

I was a little envious of its invulnerability. The wound on my cheek would leave a mark. But I did not have it in me to mind it too badly, apart from the hassle of stapling it up. That spear had been flying towards me since the day I was born, and I in turn had been traveling towards it. We cannot choose our scars.

Miwhale found me shortly before takeoff and pulled me aside by the shoulder.

“Listen,” he said, in a serious hiss. That desperation I’d seen smoldering in his eye had inflamed into a bonfire. “You’re coming with me, down into the dragonhaul day after tomorrow. It’s got to be you. Nunijh would’ve been my second but she’s totaled, and Nihoi’s got to man the ship. Ain’t a matter of if you’re up to it or no—you are. That a problem?”

“No,” I said without hesitation.

“I am a professional after all.”

###

If you were ever a child in Sabot you would have grown up playing along the beach, for Sabot is many islands and many beaches. And while at play you would almost certainly have come across something dead and strange washed up on the sand. You would be too young to know what it was. You would goggle at the mushroom-pale, deflated thing, at the shadows of organs through its skin and its too many sucking appendages. And most of all you would wonder how it would appear in its own habitat, down there at the bottom of the sea. Alive, hungry. And you would shiver, because without knowing what to name the cold hand on your neck you were encountering for the first time that great and inviolable Unknown that every man ever did and will fear into his grave.

Seeing the dragonhaul bubble up out of the lip of the world was exactly like that.

###

Sketches were made, crumpled up. Tried again. Evolved into a map. Diagrams added. A dead dragon reduced to a smudgy graphite plan. Miwhale found where he thought the head would be and circled around it until his pencil broke through the paper. A wing had fallen over it, he said, so we couldn’t simply descend on it and hoist out the brain. We would have to go in on foot, find a way to it, then guide the Zaubermanck there. There was a ridge here, he noted, where an indescribable limb had been crushed under its body. It at least looked as though climbing down that switchback slope might take us to the head. How we would transport the brain up again was yet to be determined.

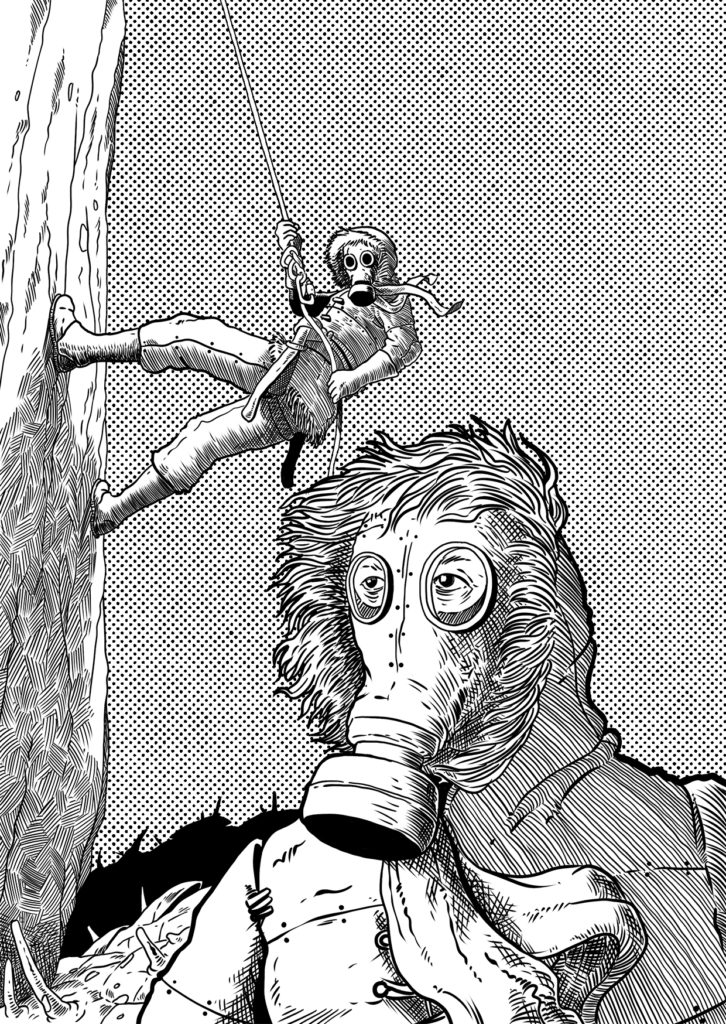

At midday, when the light was best, I belted myself into Nunijh’s fur jumpsuit and joined Miwhale in the Zaubermanck’s cargo hold. “Keep your mask on,” he said, pointing at the gas mask hanging around my neck. “It’ll be more stink than air down there. Won’t kill you right away, but it’ll make you so sick you’ll wish it did.”

He pulled a switch, and the cargo ramp opened with a rusty squeal to show how low we were hanging over the dragonhaul. Pastoral hills of degloved meat rose and fell and rose. Arcane flanges that had curled stiff in rigor mortis hooked overhead like ruined archways.

“Once we go down, we don’t come back up until we got the brain,” Miwhale said. “You left your gun, yeah?”

I nodded, and he pulled his mask up over his grimace. “Good. We run into trouble, its knives and prayers only. They say there’ll be fumes like you’d find a mine. The kind what go boom. We come this far; don’t want to go blowing ourselves up on the finish line.”

We rappelled the rest of the way down, alighting upon the dragon’s equivalent of a shoulder. I expected to sink knee-deep into its pulverized muscle but found it instead to be taut like an overfull bladder. For the first time I truly apprehended the immensity of the dragonhaul. To the individual this was a windfall. To a population, it was an economic event. Wealth would ripple out from this point of impact and upend lives like storm-tossed ships.

Miwhale heaved his pack of tools onto his shoulder and waved me over. “Stay close,” he cautioned, his voice packed down by his mask.

“We don’t have to go down there,” I reminded him. “We dig here, fill up the sheet with flesh and bone, and you’d be flush.”

“Nah.” Miwhale spat to the side—the first desecration of his new world. “Brain or nothing. Make your peace with Grimla if you’re so scared.”

By now I knew Miwhale to be a superstitious man; many times I’d seen him spit off the starboard side of his ship when he happened to roam that way, but never portside. His invocation of the storm goddess’s dread name, an ancient traveler’s taboo, told me that his heart was shaped like an arrow.

We set off down the dragon’s arm, all-too-aware of the steep and sudden slope to either side. My gas mask made every breath a chore. At the checkpoint of its uppermost elbow he hammered a cnidolantern on a spike into the ground. In case we lost ourselves in the dragon’s mazelike death-sprawl, it could help to find our way back.

The arm kinked once more before plunging into miasmic gloom. The hanging tendrils of its wing draped across our path like the fronds of a great willow. In passing through we jostled the carbonized corpses of parasites still tangled inside them. Beneath the wing it was not perfectly dark; some property of its glassy shingles transmuted sunlight into a diffused glow that was just enough to see by after letting our eyes adjust.

The dragon’s open mandibles came at us like a monster out of the ocean depths.

“Giver Sea,” Miwhale softly swore. “Couldn’t’ve dreamed it’d be that big.” He groped about his head, reaching to pull off a cap he wasn’t wearing.

All of this was too much for the world to ignore. Men would come. We were only the lucky first, and our pockets were slim. They would flood into the Kleigh, swell it with their need. The region just might come alive again. For a time.

“We’ll have to take what we can fit, I suppose.”

We slogged across a quagmire of half-frozen blood and bile and climbed to the peak of its scalp via the segmented stair of a mouthpart. As I picked my way after Miwhale through its minefield of glass-domed eyes, I felt a dizzying thrum in the back of my skull. Strange images began to drift across my thoughts—things I don’t think I possibly could have seen. Homesick memories of warm eternities. “Do you feel that too?” I asked.

“Heard of it,” Miwhale answered. “Don’t fret. It’s no more than the grumblings of a discontent soul. Their ghosts are bigger than ours, that’s all.”

He handed me a spiked cnidolantern like the ones we’d left to mark our trail. “Go screw that in over there,” he said, waving at a clear expanse of cranium. “We’ll need the light.”

So I knelt where he said and got to work planting the lantern, driving it down with the flat of my fist. Tougher work than it had looked. I could hear Miwhale unpacking his tools behind me.

Yes, we had better take as much of this cosmic flotsam as we could. We had better take it home in our hats and underclothes, because it would not last. The world would come—was already on its way—and would descend on it like so many hagfish. They would rip up the tundra for leagues around, looking for the smallest scraps of it. And when every crumb was licked up, they would go and leave the Kleigh washed up on the shore of Yeghul’s Bay like a slit Devil’s Purse.

And who could say that when the next dragon fell it would still be worth it.

It took an hour to saw out a patch of flesh several meters long and wide, and several more to hammer a circular seam in the bone beneath with our pickaxes. My gas mask made every breath an unexpected chore, and I was thoroughly exhausted by the time we were done. When Miwhale called a break I sat myself down in a crouch for a much-needed suck at my canteen, though I was quick to put my mask back on before the fumes could get to me.

“I was surprised when you said you wasn’t military,” Miwhale remarked. I could hear him organizing tools behind me. Our toil did not seem to weigh on him like it did me. I’d noticed that his own gas mask was a newer model, a zooefacted demi-creature that pumped air into him with pulmonic sacs.

“Oh?”

“Before you said you was Hussariat, at least. Then it made sense.”

“What did?” I asked.

“The blot you got on you,” he said, fairly shouting to be heard through his mask. “It’s all over, black as squid piss. Seen it all the time. Only hard folks live up in the Kleigh. You start to tell just by squinting at ‘em who’s had to shoot a man before, who ain’t. Leaves a mark that don’t go away, if you know what you’re looking for.”

“I didn’t realize.”

“Aye. I knew you was a killer before hello. So I won’t feel too bad here. Sorry friend, but I ain’t letting a lamprey get away with one more penny o’ mine.”

I turned and caught the prybar before it could a clip hole through the back of my skull. He did not seem to have expected that, because he let me pluck it right out of his hand. The other retreated to his hip and leapt back in with a carving knife like a bayonet. I flicked aside his thrust with the prybar but didn’t have the feet beneath me to dodge the heel he stabbed into my chest.

He came down on me with all his weight and pinned me to the dragon, raising his blade up high. My prybar caught his wrists before my heart could catch his knife, and the impact stunned his hands limp; the blade somersaulted and stuck itself shallowly in my shoulder. The pain was there, yes, and ordinary. Before Miwhale could think of how next to try and kill me I arched my knee into his groin and bent him in half on top of me.

We rolled around for a while, punching and cursing and trying to get a lethal grip on one another. No-one’s any good at fighting when they’ve come to that point, and I was weaker than I should have been. I could only breathe half as deeply through the gas mask, and my body was depleted from digging at the dragon. It occurred to me then that Miwhale was more devious than I’d given him credit for.

“You fucking lamprey,” he snarled, hammering me with his fists. “kill you, kill you, kill you.” I kept my mouth shut, because this was work to take seriously. “Not a drowned penny–!” And somehow, I knew that this had not been planned—at least, not from the start. Something had happened to him between then and now that had driven him to this point.

Even exhausted, however, I was the better fighter. Eventually I wound up on top of him, with my hands around his throat. He clawed at my head, looking desperately for a grip he could use against me. He got a finger under my gas mask, but the buckle had come undone in the tussle, and it came off easily. His own mask had gotten shoved up above his eyes, so I could watch as rage cooled into terror for lack of oxygen. “My boy,” he sputtered, with the last amount of air left in his mouth. After that, every breath he took in only pushed his tongue further out of his mouth.

Strangulation can be a trying way to kill a person. They fight you all the while. And you will have to look at them as you do it. Exhausting physically and emotionally. But I had undervalued Miwhale’s will to live. His fist came up and clocked me in the temple with a strength he shouldn’t have had. The old man hit hard enough to rattle my brain, and it loosened my grip enough for him to throw me aside.

As Miwhale tried to get his feet beneath him, gagging on dragon fumes, I took the chance to put some distance between us, bolting for the dragon’s snout and leaping into the frozen swamp below. I was no stranger to raw fisticuffs but there was no sense fighting fair when my life was on the line.

I was halfway up the dragon’s arm before I heard him coming splashing out of the mire, screaming my name. I risked a glance over my shoulder: the man was soaked to the groin in slushy dragonsblood, his whiskers slicked into scarlet fangs. The look in his eyes said that his arrow-shaped heart meant to pierce through mine. A pickaxe bounced in his knotty fists as he broke into a sprint.

The Zaubermanck still hovered some twenty meters above the dragon’s shoulder, its cargo bay opened to the keening wind. I prayed that the sound would carry as I put two fingers to my lips and let out a piercing, coded whistle.

Miwhale’s first swing was a hair away from tearing my scalp from my skull. Powerful but clumsy. I ducked beneath the pickaxe at the last second and delivered a punch to his gut that sent him staggering back. As it connected, I felt that it was the last good one I had left in me. I was out of fuel.

“I’m sorry it had to come to this,” I said, putting up my fists in a boxer’s stance, a threatening bluff.

Miwhale heaved the pickaxe above his head. “I ain’t-” he began to say, when the autovault hit the ground behind him like a cannonball.

He spun about as my bodyguard rose from a crouch into its full height, smothering him in its shadow. A gauntleted fist seized the head of the pickaxe and twisted it from his grip with such force that his hands were turned backwards on their wrists.

Miwhale screamed, until the autovault lifted him up in its arms and hugged him to the flat locker in its chest. I could hear his ribs giving out one by one as he was crushed against the hungry vault that had come all this way for his money. I have been told it is natural to feel guilt to be involved in such a thing, but I never understood that sentiment. Miwhale had killed himself with his own decisions.

While Miwhale thrashed and gurgled, and the autovault steadily tightened its grasp, I unzipped my jumpsuit to inspect my throbbing shoulder. The knife wound was not shallow, but not urgently life-threatening either, at least in my experience. I had plenty of time to dress it.

I glanced up at the sound of a high, wet snap. Miwhale’s body sagged in the autovault’s embrace. Blood began to trickle through the seams in its armor, down his twitching fingers. That was case resolution then. Not a successful one, mind, but not all were. I had done my duty to the best of my ability, and in that I could at least be content.

###

Weeks later, I am sitting in the waiting room outside my client’s office. From the window I can watch the well-to-do residents of Scute Mound go about their morning errands. The city of Sabot is as sunny as it ever gets, which is to say overcast. My wounds are nearly healed, though my suit hangs a little looser on my frame than it did before. In my hands is a folder containing an assortment of documents, most notably a cheque for the proceeds of forty pounds of dragon flesh and a well-used hautloft.

A secretary comes out to inform me that Mister Haethrn is ready to see me now. I thank her, gather my things, and follow her inside to deliver my final report. I am still not decided on what story I will present to my client. Many things transpired in those five days to the dragonhaul, and only so many words that can be spoken. What should I leave out to keep it brief, my client being the busy man that he is?

The journey home, at least, had been straightforward enough.

It would have been impractical to bring Miwhale’s body back to the ship, and so I left him where he lay, along with his tools. I retrieved what meat of the dragon the autovault could carry and returned to the shoulder, where I signaled Nihoi to bring the Zaubermanck lower. He confronted me in the cargo hold and demanded to know what had happened to Miwhale. I explained the events that had transpired and informed him that we would be returning to the Kleigh immediately. Without Miwhale’s expertise and manpower, the dragonhaul was no longer worth the risk to our survival. When he refused I showed him my gun and informed him that while I had no quarrel with him, the Zaubermanck would not be a democracy until such time as I saw fit to leave it. I saw him to the helm and kept my gun to the base of his spine as he put the ship in motion.

I told him that I foresaw no need to trouble one another over the next five days and went to see to Nunijh. I was apologetic, but it would be risky to have to supervise two hostile bodies. I provided her six days’ worth of rations, positioned a pail beneath her hammock, and had the autovault barricade the door. It took remarkably long for her to grow tired of screaming.

For five days I did not sleep. Part of it was practice, part of it was the pouch of watchroot extract I’d thought to bring along. When we at last touched down on the outskirts of the Kleigh I let Nunijh out and informed her and Nihoi that as was my lawful power I would be taking possession of the Zaubermanck and all its contents. By that point neither of them had the strength to argue, and we parted ways in peace. Afterwards I sold the dragonmeat and hautloft to a merchant in the Kleigh for an approximation of what they were worth, and boarded the first train back to Sabot.

I slept most of the way home.

And now I am sitting across from Mister Karlsreich Souht-Haethrn and waiting patiently as he reviews my bill of expenses. I am confident he will find them all reasonable. He is not quite so fat as Miwhale made him out to be, I think. But then, it must have been some time since he was a boy.

I had puzzled at what made him hate his father so, that he would snap up his debts solely to force their payment. Perhaps he’d grown up resenting what he thought his father owed him, and his marriage into the Haethrn family had put him into position to spite the man. Or maybe he and his mother had nothing in common. Maybe he’d grown up wanting a father so hard he’d become a cave around that emptiness. I don’t expect I’ll ever know.

And yet I wonder how things could have been different if there had not been that distance between them. If one could have reached magically across those thousand leagues and taken the other by the hand, just for a moment–what could even that touch have changed? I wonder if there wasn’t something someone could have done. Men like to think that they lean on the stories of other men with weight—knocking things over, dragging things down towards them, altering the courses of lives.

But I do not think that is so. I think that we are dice already cast by forces we will never meet. Our graves have been dug, and we are already lying in them.

I have decided the shape of the report I will give him. It is interesting to ponder what he would do with his father’s last words, if I told him, but I must not forget—I am a professional. My business is the timely recovery of debt. And this man is my employer; all he demands are the pertinent facts.

I traveled with Miwhale Souht, he attempted to murder me, and I slew him in turn.

All else is not worth the words.

________________________________________

Evan Marcroft is a half-blind yeti person with a sideways foot and an allergy to the sun. When he young he dreamed of writing important works of Earth-shaking beauty and settled for writing fantasy and science fiction instead. He currently lives in Sacramento California with a cat and a loving wife who foolishly believes he’ll someday make real money doing this. You can find his other works at Pseudopod, Strange Horizons, and Metaphorosis. You can reach him on Twitter at @Evan_Marcroft and contact him for any reason at Evanmarcroft@hotmail.com.

Miguel Santos is a freelance illustrator and maker of Comics living in Portugal. His artwork has appeared in numerous issues of Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, as well as in the Heroic Fantasy Quarterly Best-of Volume 2. More of his work can be seen at his online portfolio and his instagram.

Karen Bovenmyer earned an MFA in Creative Writing: Popular Fiction from the University of Southern Maine. She teaches and mentors students at Iowa State University and Western Technical College. She serves as the Assistant Editor of the Pseuodopod Horror Podcast Magazine. She is the 2016 recipient of the Horror Writers Association Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Scholarship. Her poems, short stories and novellas appear in more than 40 publications and her first novel, SWIFT FOR THE SUN, debuted from Dreamspinner Press in 2017.