SERVANT OF THE BLACK WIND

SERVANT OF THE BLACK WIND, by Gregory Mele

I.

The attack came at dawn.

It was not the time of day that caught the defenders unprepared, it was that it had come at all. The necropolis of Koltopec was certainly an isolated, lonely place, and there were riches aplenty buried in its many tombs and vaults, but the temple’s halls were as austere as the lonely god it served, and thus of little interest to those seeking material wealth. Xokolatl, Lord Death, cared little for such golden splendors as filled the shrines of Hatûm Sun-Lord. These things were not important in Lord Death’s realm, for the dead owned nothing; those who failed to pass through the Underworld to Hatûm’s celestial paradises were slowly stripped of all they once had or had been, even their flesh.

Called “the Patient One” and “the Final Arbiter” Xokolatl was not loved, but since all eventually came to Him as supplicants, neither was He nor His, trifled with, which was what passed through Sipan’s mind when the watch lieutenant found him in the inner shrine, and breathlessly reported that the temple was under attack. Caught in the midst of piercing his palm to make the god’s morning blood offering, Sipan stared at the man uncomprehendingly, biting off an impatient chastisement for the disturbance. But as the guardsman told his tale, the priest noticed the arrows embedded in the hide-faced shield, and the blood that ran freely from a fresh slice in the man’s cheek, just below the left eye. Realization set in: these were not tomb-robbers. The priest lay a trembling hand upon the soldier’s shoulder, unsure whom he was trying to steady. “Show me,” he said.

Rushing up the circling stone stairs, aging priest and young guardsman emerged onto the temple roof to behold a chaotic scene of madness and death. Despite high, sloped walls, and the forbidding, bronze-reinforced doors, the mortuary temple of Koltopec was no fortress, and the small company of guardsman who stood watch over the temple and its ancient necropolis were more watchmen than soldiers. All of which was far too clear just now, as dusky, near-naked savages swarmed the walls and dropped into the tiled courtyard below. Temple guardsmen rushed to intercept them, only to be struck down with clubs and copper-headed spears. Half-armoured reinforcements rushed from their barracks, still struggling to understand what was happening, their feet slipping in their comrades’ blood. Lord Xokolatl’s underworld kingdom was growing this morning; unfortunately, his new subjects were those who had already served him in life. Sipan stared out from the temple’s high roof, his mouth agape in horrified shock.

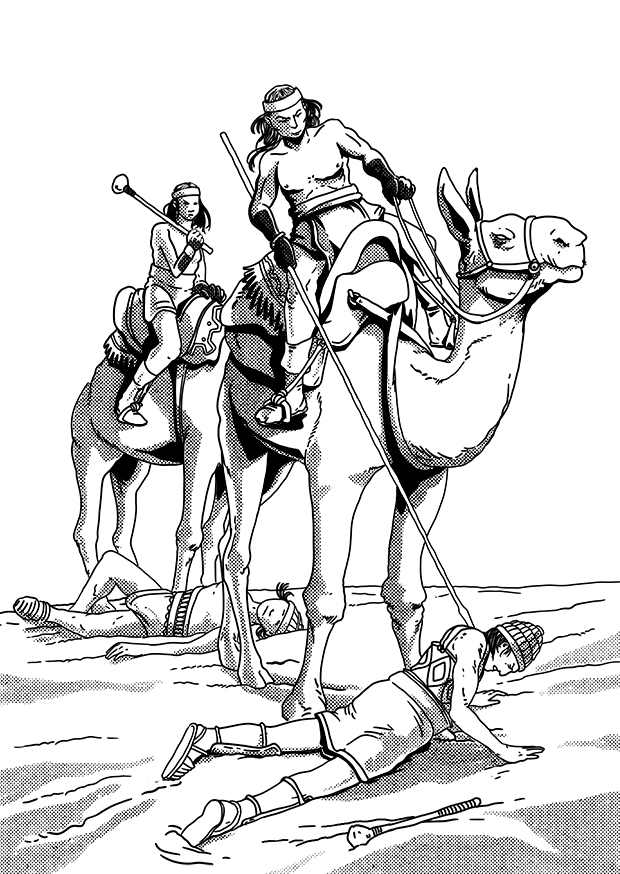

The invaders moved swiftly, unafraid of the defender’s superior arms. Brown-skinned and lanky, they wore naught but tanned hide loincloths and black face paint. Their hair was cut short on top and worn long on the sides and back, tied back by some sort of braided cord. But it was their hands and forearms, stained red to the elbows — whether with war paint or his men’s blood Sipan knew not — that chilled his heart. Savages out of the north with red hands…. these were Kwalankku, the People of Wrath. Riding on long-legged camelops, they preyed upon the other tribes of the northern Hai-Zakatla grasslands, sweeping through encampments to take food, supplies, and slaves. From time to time, the largest, most aggressive bands of Kwalankku would slip south through the mountain passes to raid the small villages and towns of the Empire’s borderlands. Now they were here, more than a week’s hard ride from the swaying grasslands they called home.

As Lord Death’s priest, Sipan had seen many die, and knew well what the tools of war did to the human body, but he had never seen those tools put to their purpose. Now he watched in dazed horror as his men died. Time seemed to slow as the priest watched one of the raiders slam the hand-long, stone ball at the end of his warclub into a guardsman’s knee, just behind the edge of his bronze greave. As the man fell, a second raider plunged his spear with ruthless efficiency into the back of his neck, just beneath the rim of his helmet; then both warriors were racing on towards new targets.

Sipan felt his forgotten companion shaking him before he heard his voice. “Holy One, what do you command?” The young guard’s voice was shrill, and his questioning eyes wild with fear. Sipan shook his head and tried to quiet the emotions roiling within him. He is no more afraid than am I, the priest thought, and only half my age. Taking a deep breath and pulling back his narrow shoulders, he tried to look as confident and in control for young…. Etzli, was it?…as he might.

“Etzli, the Kwalankku have already swarmed the wall and are opening the gate. Our men are now too few to prevent this. Certainly, Captain Ollin knows this as well.” He gestured to the courtyard just below the roof edge, “see, even now his remaining men lock shields and fall back towards the temple. Go to him now, quickly, and tell him to retreat within the sanctuary and then bar the doors.”

The young soldier’s eyes grew wide; “But Holy One, we are blood-spattered and are unpurified….”

Sipan gripped Etzli by both arms, finding a strength in his wiry and aging fingers that was born more of hysteria than resolve. “Do as I say! Think you, what shall displease Lord Xokolatl more? Entering His shrine with the stink of battle upon you, or losing His temple to these savages? I assure you boy, blood and war wounds are familiar signs in the hall of the Black Wind. Now, go!” He all but spun the young guardsman about and pushed him towards the stairs, watching the high peak of his black-enameled helm disappear down the stairwell. Now alone, the priest turned back to the battle—the slaughter, he grimly corrected himself—occurring in the courtyard below. Copper spears sank into flesh and polished stone maces shattered bones. Captain Ollin’s small band had retreated beneath the temple’s portico, out of Sipan’s line of sight. They were only eight or nine in number…one more when Etzli joined them. Even if they retreated inside the sanctuary, they would be too few to stop the raiders if they were determined to do more than loot the necropolis before returning to the sun-burnt northlands they called home.

A clatter across the flat rooftop drew his attention, just in time to see the second, copper-tipped arrow strike and skitter across the stones near his feet. He had been seen. Turning on his heel, the priest moved as swiftly as his stiff knees would allow and began shuffling down the stairs. Ollin would have to hold the outer shrine; salvation lay with Sipan and the inner sanctum.

II.

Even as Sipan was descending the stairs, Kwalankku warriors were lifting the heavy wooden beams that barred the outer gate. The gates were slowly pulled inward, and had barely opened wide-enough to admit a man when a warrior pushed through from without. He dressed little differently than the other Red Hands, but for a cloak made from the hide of one of the great cats of the northern savannah, and a fan-like headdress of yellow feathers that was held atop his red-ochre dyed hair with two long pins of ornately carved bone. A horizontal band of red paint running across his eyes contrasted with the black war paint, giving the man a wild-eyed look. This was misleading; beneath the dramatic paint, the warrior surveyed the courtyard stoically and methodically. Finding the slaughter within the courtyard to his satisfaction, he turned and looked back outside the gate, gesturing with a short nod of his head.

Four lighter-skinned, hawk-featured warriors in quilted, cotton corselets and hardened leather helms pushed the gates fully open. Seeing the battle was all but done, they slung their domed round shields across their backs by heavy leather straps and ran back outside the gate to help four others who were struggling to bring up a short, wooden ram with a bronze-bound head. Taking up the ram’s weight, the eight newcomers moved together at a trot, crossing the wide terrace that led to the complex’s central fane. Following them came a man of the same tall, long-limbed and broad-shouldered race. His skin was much lighter than that of the ram crew, with only a slight, coppery tint, but his features had the same, sharp angularity. Thick waves of auburn hair flowed from beneath a tall, bronze helm, and piercing, almond-shaped eyes the color of fine jade surveyed the world from their perch above a sharp, hooked nose.

The newcomer joined the Kwalankku chieftain, who watched the attack on the gate from atop his massive mount’s tall, humped back. Camelops were absurd-looking creatures: something like giant, humpbacked llamas, with over-sized heads and shorter, thicker necks; their long, knobby kneed legs ending in wide, three-toed feet. Like llamas, the creatures were prone to spitting when agitated; unlike llamas, they were equally prone to kick and bite, a serious danger from a creature three-hands taller than a Naakali chariot-horse – the Kwalankku claimed that an enraged camelops could bit clean through a man’s neck.

Right now, the creature seemed, if not placid, at least controlled, but the tall, auburn-haired man was careful to keep a polite distance as he spoke to the chieftain, smiling with a thin grin that tilted upward the left corner of his mouth.

“Your people have done well, Nuukpana.” His soft, sibilant voice could just be heard over the moans and cries of the dying. A long, high-pitched cry burst from the mouths of the nearby tribesmen; a strange ululation that sounded at once triumphant and mournful. The tall commander turned brilliant green eyes toward the warriors, his grin fading into a look of annoyance at being drowned out by their keening. He sighed and looked back to the chieftain. They had done as well as could be expected of any of the brown-skinned savages that called Tehanuwak home. Gods, why had his ancestors ever come to such a wretched place?

“As I was saying, you have done well, but you must make sure that none of these,” he waved dismissively towards the guardsmen lying scattered across the terrace in widening pools of their own blood, “still live when we are done here.”

Nuukpana shrugged and made a sound that might as easily have been a short laugh as a grunt of disgust.

“This is simple work, Tall Man,” he said in thickly-accented Naakali. “We came to fight warriors of the Empire and found children in men’s bodies instead. It is beneath a warrior’s dignity to cut the throats of such as these; let Vukub have them.” He gestured toward the sky, as if this somehow explained his meaning.

No doubt, one of the gods these savages call upon, the nobleman thought angrily. “I neither know nor care for your Vukub, any more than the Kwalankku care for Lord Xokolatal, whose temple you have just defiled. But I do care for the agreement Nuukpana made to me over pipe smoke, swore to in blood, and expected to be paid for in bronze, gold and balché. Payment he shall most certainly receive…after,” he drew the word out through clenched teeth, “he has done that which he has been asked to do.”

Nuukpana shrugged and made another noncommittal grunt. He turned his head and spat, then wiped his hairless lips with the back of a scarred, sun-bronzed hand. “Then it shall be as Tall Man says. If Empire men are too good to cut each other’s throats, then the People shall do it.” As if by the passing of divine judgment, there came the first boom of the ram slamming into the fane’s heavy doors. “But only younglings who have taken their first blood today will cut the throats. I will not shame my warriors, Tall Man, not for all the sun-metal axes and war clubs in your Empire.”

“I see you said nothing about refusing the balché, Nuukpana,” the nobleman said with a wry smile.

The chieftain grinned, showing wide, yellow teeth with an almost ridiculously large gap between the two centermost. “You southmen are soft, Tall Man, but the honey wine you make is hard to turn away. Sometimes, even for honor.” Clucking to himself, he turned from his employer and called out to his warriors in their own, harsh tongue. The tall nobleman crossed his arms and watched, wondering what orders the Kwalankku chief had given, and whether he need suspect betrayal. He relaxed when a young warrior with spatters of fresh blood on his chest and face knelt beside a fallen temple guardian and unceremoniously cut his throat with a keen-edged, flint knife.

Barbarians, the nobleman of the Empire thought, but they keep their word. Or perhaps, more accurately, they keep their word because they are barbarians. Clenching his star-headed mace more tightly, he stepped into the courtyard and began walking towards the source of the battering ram’s sonorous song.

III.

Sipan cursed his arthritic knees as he limped down the broad stone steps to the main floor of the temple. Unlike the houses of his brother and sister gods, Xokolatl’s shrines were not tall pyramids whose sanctums reached towards heaven. They were gates to the dark and secret places of the world, and their design reflected this: single-storied, comprised of broad, colonnaded arcades surrounding a single, recessed sanctum. It was that outer shrine, with its elaborate, painted murals of the deceased’s journey to the afterlife, and a massive statue of the god to which the remaining guardians now retreated, herding a small congregation of panicked acolytes, priests and servants before them.

But not Sipan. When he saw two of his priests still half-dressed from being awoken by the assault, stumbling along behind the shoves of guardsmen, the aging high priest stepped back up into the stairwell, hiding himself from their sight. They would want him to come with them, to lead them and to give comfort…and he had none to give. What he needs do might save them, it might not, but it was his foremost duty as Lord Death’s chosen Speaker in this place.

The last of the soldiers rushed past. Sipan stepped out from the stairwell, and immediately turned along a side arcade that led behind the temple sanctum. Moving as quickly as his stiff limbs would allow, he hurried through the arcade and into a small chamber filled with wooden trunks and a peg-wall, from which hung a number of embroidered stoles, head-bands and feathered-headdresses. This was where the priests prepared themselves for the elaborate funerary rites to ensure the departed’s passage through the Underworld. Sipan took one of the crimson-colored stoles and slipped it around his neck, then threw open one of the heavy clothes-chests and began frantically searching through the ritual vestments. After a moment, he stopped. Looking down at himself, he frowned. Dressed in only sandals, a pleated black kilt and the painted and bejeweled leather pectoral collar he had donned for the dawn rituals, there was simply no time to struggle into the full, ceremonial regalia of his office, especially unaided. It was not just formality; the gods were fickle creatures who needed to be both praised and cajoled, and the sights, smells and sounds of the priestly craft allowed the supplicant to draw closer to his or her divine patron. But there was something that thinned the Veil between worlds more assuredly than fine vestments, and that Sipan would offer as much of as was needed to draw Lord Xokolatl’s attention.

Pinching his lips together with grim determination, the priest turned to a table set with a small idol of Lord Death, silver wash basins and pitchers, and several black earthenware jars. Kicking off his sandals, Sipan washed his hands while reciting a prayer of purification.

“We, called Carrion Crows,

the priests of Xokolatl,

are the Keepers of the Dead.

The guardians of glorious tombs

and humble graves.”

Opening the first jar, he dipped his fingers within and began to spread a heavy, white paint of crushed chia over his hands and face. The god might forgive some informality, but one did not appeal to the Underworld wearing the guise of the living. Once his face, hands and feet were chalked white, he opened the second jar and with practiced ease, used the ash paste within to darken the hollow around his eyes, trying to ignore the booming he now heard issuing through the fane’s sealed doors.

“The earth is a grave and nothing escapes it;

nothing is so perfect, that it does not descend to its tomb.

Even a carving cut in stone fades, the green feathers of the ketzal bird lose their color, the sounds of the waterfall grows silent

when the dry season comes.”

There was no time to paint the intricate details of bones and teeth, but Sipan believed that a semblance of the newly dead would suffice to avoid Lord Death’s wrath. Bowing to the small statue on the table, he took it in his hands, and holding it aloft before him like a lantern, turned to the small, non-descript stairs at the far end of the room and began his descent into the temple’s inner sanctum.

IV.

The gates to the fane burst open, and the blood-spattered warriors of the People of Wrath leapt over the ram and pushed past the southern soldiers, anxious to be about their gory work. Captain Ollin rallied Koltopec’s remaining defenders, and their bronze spears flicked out like serpent’s tongues, slicing through brown limbs and naked bellies as the first wave of raiders attacked. But there were far more Kwalankku than guardsmen, and as the first attackers were cut down, others slammed against the defender’s shields. Had this been one of the temple legions of Golden Hatûm or Bloody-Handed Tuwâs, Master of Righteous War, they would have known how to defend a breach by forming a pocket the invaders must enter one or two at a time, while facing four of their spears, or how to beware, should the besiegers choose to use the ram itself as a weapon.

But these things were unknown to the guardians, and young Etzli was the first to be struck by the heavy ram as it crashed into their shield wall, driving the rim of his shield back into his knees, so that his body pitched forward. Instantly, one of the raiders gripped the back of the youth’s helmet and pulled his head forward, hurling him out of the line. Ollin lashed out with his commander’s mace, crushing the savage’s hand, but was unable to prevent a heavy club from shattering the back of the fallen guardsman’s skull. The ram men swung the heavy beam again and let it fly into the opening caused by Etzli’s fall, fouling the spears of the guardsman behind him. For one moment, the small line of shields was broken, and that moment was all that was needed for a well-thrown spear to strike Ollin as he tried to step into the gap. The captain staggered back, and with a howl, two of the Kwalankku warriors leapt against him, swinging their stone clubs with the ferocity of rabid wolves.

Confused moments of barbaric howls and the ring of stone and bronze, and then the last of the soldiers were dying and there were none to defend the temple’s less martial inhabitants. Clubs shattered shaven heads and flint spears sank deep into soft bellies. The temple women — wives, servants and priestesses alike — suffered the worst; their screams ringing throughout the temple halls until they were cut short by repeated cuffing, or silenced forever by the cruel work of flint and copper knives.

The nobleman entered last, stepping carefully over the fallen guardsmen, not wishing to stain his elk-skin boots in their blood. He found Nuukpana in the shrine, assessing the small collection of women and boys that knelt, heads to the ground, hands behind their heads. They had been placed before the cold stone idol of Xokolatl, who gazed out of His desecrated shrine with unseeing, turquoise eyes. One Kwalankku warrior was busily cutting away the captives’ clothing, another stripped them of any jewelry, while a third roughly cut off the women’s hair at the nape of their necks. As nomads, the People of Wrath wore their treasure on their bodies and their appearance was the source of their personal pride; thus, they let their slaves wear nothing at all.

The nobleman scanned the shrine, absently taking in the elaborate murals of Xokolatl that lined the walls and proclaimed His authority. Here, the alabaster corpse-god plucked the breath from a dying warrior, there He laid a bony hand upon a village bedeviled with pestilence. On one side the hall was decorated with owls, the Callers of the Dead, and Xokolatl was shown as Lord of Tombs presiding over embalming and funerary rights; on the other, carrion crows led a procession of the dead, from peasant to Emperor, to the god’s throne of bones deep at the heart of the Underworld.

Considering the subject matter, the nobleman thought, the blood spatters hardly look out of place.

Seeing his patron enter, the Kwalankku chief smiled another of his gap-toothed grins.

“These temple-men may be women in warrior’s clothing, but the People found some real women as well,” he reached down and grasped one of the women by the thick scrub that remained of her once lustrous, auburn hair and turned her face forward. She whimpered fearfully, but made no move to resist as he fondled a soft breast in much the way one hefted a tobacco pouch. “This is good treasure, Tall-Man; these long-legged women of yours will bring the People strong new warriors.”

The nobleman frowned. He found the sullying of Naakali women by these savages distasteful. One priestess was worth five of these animals; a Godborn one, who could trace her ancestry back to Iperboritlán, lost across the eastern sea and beneath the Great Ice? She was worth more than their entire, dirty tribe. But, he reflected, they should be grateful those animals wished to drag them back across the grasslands; otherwise, he would needs put them under the knife here and now.

“We did not discuss the taking of slaves, friend Nuukpana,” he saw the chieftain’s smile begin to fade, and held up a hand in dismissal, “but did I not say that if the Kwalankku did as was asked, I would be generous? You may have them, and so too, any of the war-gear you find upon the dead.”

Instantly, Nuukpana’s smile returned. The warrior tasked with cutting away the new slaves’ clothes had stopped his work to watch the interplay between the two commanders; he asked a question of his leader in their guttural tongue. “He says to ask, ‘what of the balché ‘?”

One of the Naakali soldiers laughed, and the tall noble tried not to visibly roll his eyes. Simple creatures, simple needs. “You may take what you will from the store-houses. You will find balché aplenty. However, the library and personal chambers…,” he saw the lack of comprehension on the chieftain’s face, “when you come to a room filled with rolled tubes of writing, or the sleeping rooms of the priests, these are not to be touched. Understood?” The stocky tribesman nodded, and spoke to his warrior in their own tongue. Seeming ameliorated, the warrior nodded, and then pressed the head of the youth at his feet back against the cold tiles before tearing away his kilt and slicing through the straps of his sandals with practiced ease.

The tall nobleman turned his attention back to Nuukpana. “And the high priest? Your men have not found him? They understand that he is needed alive?”

Nuukpana nodded impatiently, far more interested in the naked, former priestess; he had rolled her to her back and was continuing to inspect her the way one did a new dog. “Yes, yes, Tall Man. My warriors know. Find the old, bald man, bring him to you.” He looked up and shrugged, “but what we do not find, we cannot bring.”

Whatever his patron was about to say was cut short as a strange howl that was neither wind nor human scream, but something in-between, issued from beyond the defiled shrine.

V.

The inner shrine was far smaller than the public sanctuary above. The walls and ceiling were painted in darkest black, the floor a blood red. The subject of the murals painted on that dark backdrop was also far simpler: on either sidewall, naked men and women, devoid of all rank and privilege in death, climbed over the Underworld’s sharp, obsidian terrain, which slowly stripped them of their final identity — their flesh — until they stood as mere skeletons before the Tomb Lord’s throne for judgment.

The shrine’s far wall was also painted in funerary black, but was unadorned with painted cult mysteries. Instead, a square archway of niches had been cut into the wall; set into nearly all of them was a human skull. But each skull had been covered in a mosaic of carefully cut and fitted turquoise and jet, and wide discs of mother-of-pearl filled the eye sockets, creating a semblance of the wide-eyed grin of the insane. The skulls’ “eyes” had drilled holes at their center and through both these “pupils” and between the jaws the soft, yellow glow of votive candles glimmered forth.

On a raised dais set before this macabre archway was an image of Lord Death himself. This was no cold idol of stone, but rather the desiccated flesh of one long dead; preserved against the years by the embalmer’s mysterious arts. They had seated the dead man cross-legged upon a disc of polished obsidian, and dressed him in raiment fit for a lord of the Underworld. The mummy’s head was wrapped in a heavily padded, cotton cap, to which was pinned an enormous crescent headdress made of beaten gold; from its brow band a long golden nasal descended, ending in a second crescent that covered the long-shriveled nose and dried lips. Brown, desiccated earlobes wore two massive golden ear-spools, masterfully inlaid with turquoise. Heavy, golden necklaces of stylized crows and owls hung around the thin neck. The body of the corpse-idol was dressed in a fine tabard, fringed with embroidered triangles and covered with gleaming squares and diamonds of beaten gold that caught and sparkled in the lamplight. A pair of massive, golden pectoral shields in the form of leering skulls pinned in place a cloak of fine llama wool that had been woven in alternating bands of red and black. In the mummy’s right hand was a scepter of carved bone, perhaps the length and thickness of a human femur, while the left held an overseer’s scourge of braided leather, each of its small tails tipped in the barbs of scorpion’s tails. Withered feet had been carefully dressed in copper sandals with soles of woven cord. On the dais before this fearsome idol was placed a pointed rattle stick, a mirror of polished obsidian, a golden cup embossed with owls and a clay whistle, a bit smaller than a man’s fist, formed in the semblance of a human skull.

Symbolically dressed as a penitent coming before the throne of Lord Death, Sipan bowed his head and lifted his arms, palms uplifted, approaching the sepulchral altar with the short, shuffling footsteps required by ritual.

“We, called Carrion Crows,

the priests of Xokolatl,

are the Keepers of the Dead.

The guardians of glorious tombs

and humble graves.”

When he reached the altar, the priest fell to his knees, cringing in pain as the swollen joints struck the hard, crimson-painted stone. Lowering his head to the ground, Sipan kissed the foot of the altar three times, then slowly rose, bracing his hands against the stone pedestal to push himself upright. Bowing again his head in supplication, he took up the long rattle stick from the altar and began to shake it in a slow rhythm, the call of Kekoatl, the Serpent Who Strikes the Heel. Turning to each of the shrine’s four quarters, the old priest intoned:

“We, called Carrion Crows,

the priests of Xokolatl,

are the Keepers of the Dead.

The guardians of glorious tombs

and humble graves.”

Letting the rattle fall to hang from his wrist by its rawhide lanyard, Sipan sliced his priest’s thorn ring through his left palm without hesitation, cutting just below the thin, thick line of an old scar. Running his right thumb along the wound, he smeared his blood first across the idol’s shriveled lips, and then his own. Taking up his rattle once more, he began to shake it before the idol’s unhearing ears:

“Xokolatl! Lord Death! We, the Carrion Crows, are your servants!

Those to whom You hath said;

‘May the Black Wind howl and Life wither

should the House of Xokolatl be disturbed.’

“We know it is true

that we must perish,

for we are mortal men.

You, the Arbiter of Life,

have ordained it.

“We wander the world

in our desolate poverty.

The desolation and pain of life!

We have seen bloodshed and pain

where once we saw beauty and valor.

“The earth is a grave

which nothing escapes;

nothing is so perfect,

that it does not descend to its tomb.

A carving cut in stone fades, the green feathers of the ketzal bird lose their color,

the sounds of the waterfall grow silent

when the dry season comes.

“The bowels of the earth are filled

with dust once flesh and bone,

once living bodies of men:

who sat upon thrones,

decided cases, presided in council,

commanded armies,

conquered provinces and destroyed temples,

exulted in their pride, majesty, fortune and praise.

Where are they now? Vanished are these glories;

nothing recalls them but the written page.”

Allowing both the power of the ritual, and the need of his cause, to consume him, Sipan ignored the sharp sting in his wounded hand as he pressed his bleeding palm to the mirror and drew it in a slow circle, staining its smooth, black surface red, all the while continuing to shake his rattle in a slow, steady rhythm. From here, there could be no going back; the god would claim His price, whether He answered or no. Gathering his strength and giving himself over to the ritual, the priest threw back his arms, his voice rising, the rattling growing more emphatic as he made the invocation:

“But you, oh Watchful One,

You Who Dwelleth on the Threshold

You are the Judge and the Protector of the Dead.

Come now, Lord Death!

Come, O Bringer of Sorrow and Reliever of Misery.

“Say unto the defilers:

‘I fulfill the Law and the Law demands your blood!

I am Xokolatl, the One to Whom All Come;

The Devourer, the Necessity.

I am the Keeper of the Tomb and the Lord of the Black Wind.

“I am the cry that catches in the throat,

the newborn that draws not breath;

the sob that shatters stone.

Impaled on my teeth, you shall be blessed,

for you will glimpse the truth of your own dark heart.

“As long as you breathe,

I shall grind your bones

and chew your flesh,

to tear the darkness from your heart.

Fleshless, you shall be forgotten.'”

Sipan crossed his arms and bowed his head low. Letting the rattle drop from his hand to hang from its lanyard once more, he took up the skull-whistle and held it aloft.

“We, the Carrion Crows,

the priests of Xokolatl,

are the Keepers of the Dead.

The guardians of glorious tombs

and humble graves.

Mighty Lord, hear our call!”

With a deep breath, Sipan sounded Xokolatl’s sacred instrument. The Black Wind’s mortal voice was horrific; the sound of rushing wind and a woman’s scream that ended in a choking gurgle as the priest’s exhaled breath came to an end. Now, only the offering remains. Taking another deep breath, he called the Black Wind once more.

VI.

The old fool made himself easy to find, the nobleman thought, as he hurried down the stairs, following the horrid screech of the skull whistle. Only his soldiers, familiar with the rituals of Xokolatl, ran ahead of him; the barbarians had looked at each other and refused to leave the outer shrine, despite Nuukpana’s commands, and probably to his own superstitious relief. Well, they were neither needed, nor particularly wanted, for what was to come.

When he entered the inner shrine, and found the aging priest standing beside the macabre altar with its mummified deity, the nobleman was filled with disgust; he had heard rumors that the mortuary temples had such ghoulish idols, no doubt a “reward” granted to some long-serving high priest. The old priest looked hardly less ghastly himself. Thin shouldered and wiry, he was half-dressed in priestly vestments and painted to look like a newly-dead corpse. Prescient of him, the nobleman thought. The priest peered at the nobleman in the dim lamplight with eyes grown weak with age. Was he recognized? No matter, whom would he have a chance to tell?

He allowed himself a moment of perverse pleasure as the priest’s eyes grew wide, taking in his height, his fair skin and green eyes; the well-trimmed mustache and beard so few men of Azatlán could grow.

“But you are a Great One of the Empire…Tehanaakali, “First Born”… one with the blood of lost Iperboritlán strong in his veins….,” he seemed stunned, uncertain. “You…. would do this to your own people?”

“My people, you brown-skinned dolt? My people were conquerors, who were masters of the world ere our black-sailed ships ever crossed Okeanos’ waves to come to this wrertched land; yours are merely the by-blows of mating with the animals they conquered. You are no more ‘my people’ than the savages I came here with; which is why your pretty paints and shabby robes do not impress me. Let us make this easy on us both: where are the Scrolls of Tzokulum?”

The old man shook his head and pursed his lips. There was no point in feigning ignorance; this man was one of the Imperial elite; if he knew enough to know that Tzokulum, last Emperor of the milk-skinned Godborn of Iperboritlán was buried here and had been determined enough to plan this raid, he was well-aware that the mortuary temple’s high priest would be familiar with his tomb-hoard. So, he ignored the question entirely.

“My appearance is not to impress you; it is to honor Lord Death. Great One or no, your arrogance and your desecration has doomed you,” he pointed at the nobleman with a hand that bled freely and blew into the carved skull-whistle, its eerie wail filling the small shrine and piercing the noble’s ears as surely as a skewer. One of the soldiers visibly blanched; another lifted his axe and started to move forward, but his master stayed him with a hand upon his shoulder.

“Allow the old fool his pantomimes,” he said, then turned his attention back to the old priest. “Understand, ‘Holy One’ that your Corpse-God ceased to frighten me when I was a boy.” He began slowly walking toward Sipan with pantherine purpose. “What armies march at His command? How many Emperors have called upon Him when choosing their throne-name? What sacrifices can He command, lest the sun cease to burn, or the crops go fallow? No, old man, your god is little more than a dog who feasts upon the table scraps of His betters.” He had now come within a stride or so of Sipan.

“You young, arrogant fool,” Sipan snapped, “Lord Xokolatl commands no legions, for He is there in the red ruin all warriors wreak; no Emperor takes His name, for His concerns are not of this life, but what comes after. As to sacrifices…. oh, He asks much, just not for strangled maidens, burnt warriors or drowned babes; what need is there of such for one to whom all life is eventually offered?” His voice was proud, but as he spoke, he took a trembling step back.

His tormenter laughed, a deep, throaty sound of mockery.

“Well, then today I have been a greater priest of Xokolatl than you, Holy One.” He held his hands out as if to encompass all around them, “For have I not made quite an offering?” Then his face grew hard, and his hand slid a bronze dagger from its belt scabbard. “Now, enough theology. Answer my question.”

But the old priest said nothing, only stepped back furtively, until the hard stone of the altar pressed into his back. The nobleman shrugged, “So be it.” He waved the dagger dismissively towards his soldiers. “Hold him, still.”

Sipan lifted the whistle to his lips once more, but the soldiers swiftly crossed the chamber and were upon him, wresting away the instrument, grasping his thin wrists in broad, scarred hands, and bending him back over the altar, until his shaven head rested at the mummified feet of the idol. Attempting to sit upright, the high priest looked down the length of his body and saw the nobleman standing over him, delicately fingering the dagger’s point. “Again, old man, where are the scrolls?”

The priest struggled furtively and shook his head, “No doubt in his tomb; if you wish them, desecrate that as you have this temple.”

The tall nobleman chuckled, “Well-played, but I know more of priesthoods and their covetousness than you give me credit. The last sorcerer-king of the Godborn is buried with his vast collection of magical writings, and the temple of Xokolatl is left to watch over them, yet none are left to watch over the temple itself. Do you think your predecessors waited an hour after the burial ceremonies were complete before they reopened the tomb to loot it, or where the scrolls never placed in the tomb to begin with?” He held up a long, well-manicured hand, “No, please, don’t spend your precious breaths on outrage, the question was rhetorical. What I wish to know is where the scrolls are now, and that is an answer that I will have.”

Sipan pressed his lips together tightly and turned his head away. When he felt the dagger’s keen point pressed against this thin belly, his mouth grew dry and his breath caught in his throat. “Lord Xokolatl, give your servant strength” he whispered, then gasped as he felt the sharp bronze slowly trace a red path across his flesh.

The nobleman smiled cruely, tapping Sipan lightly on the forehead with the dagger, now red with the priest’s own blood. “I think the time for prayers has passed, old man. I assure you, I am very good at making men talk.”

He was. The howls of pain that filled the small shrine were almost indistinguishable from the wail of the ceremonial whistle that had preceded them, and in the end, the old man told young tormenter what he wished to know. Sipan’s final reward for betraying his temple’s secrets was feeling the dagger slowly slice through the taught muscles of his belly as he was bent over the edge of the altar like a sacrifice to one of the Empire’s hungrier gods. His cries were little more than blood-choked gurgles, however; having learned what he wished, his slayer had then taken his tongue.

The nobleman stepped back to admire his handiwork, tearing free the old priest’s kilt and using it to wipe the blood from his dagger. He stroked his cheek with the tips of two fingers and looked with distaste at the droplets of blood he found there.

“I believe I saw a wash basin above. You won’t mind if I make use of it, will you, old man? No, I thought not.” He nodded to the soldiers and they released Sipan, who clung to the altar with the last of his strength. “I will leave you now, to be about your dying. Don’t take too long with it, you wouldn’t wish to keep your god waiting, hmm?” Sheathing the dagger, he absently continued to wipe at the blood on his hands. He turned his back on his victim, the soldiers dutifully following him. They left Sipan to die alone in pain and humiliation.

Alone and forgotten, none saw the priest’s trembling hand press itself deep into the bloody gash in his belly, before holding it forth to the Tomb Lord’s idol. None were present to see the smile that spread across his ruined face. As his own vision faded, he thought that no sight had ever been more beautiful than the brown eyes that gazed down upon him.

VII.

The Kwalankku might be willing to desecrate a foreign god’s temple, but that did not mean that they were willing to spend a night in its blood-spattered precincts. Dragging the captives into the outer courtyard of the temple complex, they lashed them together into a slave coffle and loaded both slave and pack-llama with the loot that would be most treasured in the northern savannah: items of gold, bronze tools, fine woolen blankets and casks of the good, sweet balché they so craved. The warriors began leading the slaves out of the temple gates and through the necropolis, but Nuukpana tarried beside his long-legged camelops.

“You should be going now, too, Tall Man.”

The nobleman, freshly cleansed of Sipan’s blood, smiled wryly, “Surely you are not worried about my well-being, Nuukpana?”

Stroking his mount’s neck, the Kwalankku chieftain frowned and shook his head, “It is not wise for a warrior to stay too long in the house of a god not his own; less when he has spat upon that god’s honor. Best to go from here now.”

“Your concern is touching, of course, but I think it best if Nuukpana worries about crossing back through the mountain passes and onto the grassy sea of Hai-Zakatla before the Empire knows what has happened here.”

He was given a shrug in reply. “Nuukpana is not a fool, Tall Man, and sees much that is not said. You wish the Empire to chase the People through the mountains; in this way, your deeds are hidden by our own. Why this is does not matter to me; the People are not afraid of the Empire, nor any who is fool enough to follow us to the Hai-Zakatla.”

“Your confidence is impressive; your disinterest in my affairs appreciated.” He lifted his hand, palm up, in the greeting-farewell sign of the northern tribes. “May you enjoy both your new slaves and your balché-wine.”

Leaning down Nuukpana pressed the palm of his own right hand to the nobleman’s, then swung himself onto the camelops’s slightly humped back. He looked down and smiled with that ever-mocking, gap-toothed grin, “May your belief that you are Taller than the Death God prove true.”

***

That evening, the new master of Koltopec sat alone in the temple’s library, drinking the best of the priests’ balché from a golden, ceremonial cup as he poured over a stack of ancient scrolls, his tall helmet sitting on the table with his scabbarded short sword beside it. While the savage’s warning might have been born of superstitious dread, there was a very practical reason for haste: sooner or later pilgrims, mourners or merchants would enter the valley to call upon the temple, and the slaughter would be revealed. There was a limit to how many unwanted visitors his eight retainers could handle, nor was there much sense in going to the trouble of recruiting barbarians to attack the necropolis, just to leave behind corpses clearly struck down by good Naakli weapons.

As if to make his thoughts manifest, a man’s short but agonized scream broke the silence. The nobleman looked up from the scrolls, his hand instinctually reaching for his sword. After a moment, all was again silent. No doubt, one of his men had found another of the temple servants hiding in one of the lower chambers. After a minute or so to assure himself that all was quiet, he turned back to his work. He did not think the old bastard had deceived him; these clearly were scrolls from Tzokulum’s treasure hoard. The trick was to find the sorcerous texts he sought and replace the rest. The longer it took the temple hierarchy to suspect what had really happened here, the more likely his success would be.

He cast his eyes over old, dried sheets of bark-paper stitched together at each end to form a folding codex of faded hieroglyphs and strange illustrations, and his eyes grew wide. This was more like it! Anxiously, he began to scan the complex glyphs, then turned to the next, thin bundle of skins, seeing that what had once been scrolls rolled in the ancient fashion had been cut, folded and stitched into a codex. Looking for the “Scrolls of Tzokulum”, he had twice passed them by. A clever way to hide a series of scrolls, he thought, make them into a book.

He was so engrossed in both his discovery, and in his self-congratulatory celebration over outwitting the Tomb Lord’s priests, that he did not hear the scraping of copper sandals as their owner entered the library. It was the strange combination of sickly-sweet scented kopal and the harsh, metallic odor of fresh blood that stimulated some autonomous part of the nobleman’s mind, telling him that he was in the presence of the other and caused him to turn his head. Seeing the tall, walking husk in its golden accoutrements, he leapt to his feet with a curse, knocking the low table over, ancient scrolls and codices falling to the floor unnoticed.

The corpse idol spoke not, but the very living, very aware brown eyes looked at the nobleman with amusement. Its dry, blood-painted lips cracked and split as it attempted to smile. Its intended victim scrambled back, stumbling on a stack of discarded scrolls as he fumbled for his sword. The blade hissed from its scabbard as the thing strode toward its victim, outstretched hands still dripping with fresh blood, its limbs moving with a preternatural smoothness of motion. Claw-like hands reaching for him with horrific strength as the nobleman forced himself to grip the creature’s shriveled neck and plunge his sword into its belly. The sword tore through leather skin, piercing an empty body-cavity whose organs had been removed by embalmers now long-dead themselves. The horrible, undead thing pressed inexorably forward, and slowly the arm that held it at bay began to bend. It was too close to cut effectively, almost too close to use the sword at all, so in desperation, the nobleman drove the sword through its body one last time, transfixing it. Drawing his dagger, he attempted to thrust the shorter weapon up under the breastbone. The dead were mummified with their hearts intact; if he could pierce that….

With a final push, the creature dug its bronze hard nails into his shoulders and slammed into him with its dried body. They crashed to the ground together; the dagger pushing deep into dead flesh as undead jaws found the pulse in a living throat. In a voice that rattled like a pit-viper’s tail, the guardian lifted its bloody lips and rasped, “Freedom…!”, then hungrily bit into its victim once more.

Blood spurted and flowed unnoticed onto the last of Tzokulum’s scrolls, a necromantic text long believed lost…

VIII.

It was four days after the slaughter when a small party of merchants arrived at Koltopec to provision the priests with fresh maize-flour, dried fruit, turkeys and spices, but found that none within the mortuary temple would need their services ever again. Fearing the raiders might still be in the area, the horrified merchants fled back to Mishalál, the nearest city, and reported to the governor what they had found. Two more days passed before messengers reached the mother temple, and two more after that before a small company of Xokolatl’s priesthood arrived at the necropolis to tend the dead and quiet any hungry ghosts. By this time, the bodies had begun putrefying in the early summer heat, and there was little to be done for the mortal remains than prepare a mass grave, perform the necessary rites and implore the Tomb Lord to recognize His own.

When they found his broken body, with its horrid manner of death writ large upon blackening flesh, it was all-too-clear what had happened and why. Unlike the other victims, the priests hurriedly carried the body into the embalmery. There, they removed the liver and entrails, and bathed the battered limbs and newly-hollowed body cavity before carefully stitching closed both the pre-and-post-mortem wounds. Burying the body under a high mound of nitrous salts they left it for two moon-cycles, until the natron had stripped all of the moisture from its flesh.

Freed of the salt and bathed with palm wine, they dressed him in a golden tabard and cotton cap, attached the fringed cloak to his chest with golden pectoral pins, and covered his feet with copper sandals. The dried earlobes at first resisted the pull and tug of the large ear-spirals, but yielded at last. Hanging precious necklaces around his neck, they placed the heavy golden headdress upon his head and pinned it into place.

After so much time in the heat, Sipan, never a fleshy man to begin with, was recognizable more from the priestly garments they found lying around his body than from his hollowed and marred face. Carefully removing his head, they placed it into a cauldron, the boiling water stripping away the flesh. Craftsmen carefully and loving affixed panels of turquoise and jet, filling the empty sockets with “eyes” of mother-of-pearl. When the time came to place the scepter and scourge in the mummy’s withered hands and carry him in a solemn procession through the necropolis, back into the mortuary temple and at last down into the inner shrine, Sipan’s bejeweled skull was held aloft and led the way. They set his skull into one of the empty niche’s and placed a votive candle it its mouth. As the candle was lit, the priests folded the new corpse-idol’s oddly pliant limbs so that he was seated cross-legged upon the obsidian disk. Lord Xokolatl was represented in His inner temple once more.

That night, after the moon had set, they burned the remains of the old guardian beneath the open sky to the howling wail of skull whistles. Then, and only then, did the high priest return alone to the inner sanctum and perform the last stage of the ritual, delicately slicing through the fine threads that held shut the guardian’s eyelids, opening its wondrously green eyes to the world.

________________________________________

Gregory D. Mele has had a passion for sword & sorcery and historical fiction for most of his life. An early love of dinosaurs led him to dragons, and from dragons…well, the rest should be obvious. From Robin Hood to Conan, Elric to Aragorn, Captain Blood to King Arthur, if there were swords being swung, he was probably reading it.

While a student at the University of Illinois in the early 1990s, he discovered that there was a vast collection of surviving technical works on fighting with the sword, rapier, lance and axe. Sword in one hand, book in the other, he never looked back. Since the late 90s, his passion has been the reconstruction and preservation of armizare, a martial art developed over 600 years ago by the famed Italian master-at-arms Fiore dei Liberi. In the ensuing twenty years, he has become an internationally known teacher, researcher, and author on the subject, via his work with the Chicago Swordplay Guild, which he founded in 1999, and Freelance Academy Press, a publisher in the fields of martial arts, arms and armour, chivalry, historical arts and crafts.

Greg lives with his very tolerant family in the Chicago suburbs.