THE REPRIEVE

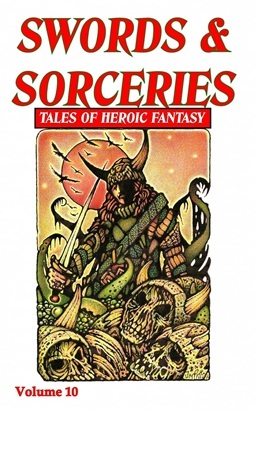

THE REPRIEVE, By Darrell Schweitzer, artwork by Andrea Alemanno

There was an intruder in the room.

Prince Tigranes drew his throwing knife and whirled about, searching the night-time shadows. Curtains billowed from open windows, rustling gently. There was no other sound, but he knew he was not alone. He had an instinct for that, even as he had a talent for throwing knives. These were decadent times in Riverland, not a reign of virtue at all. While he was a man of culture and intelligence, and, he liked to think, some sensitivity, his primary talent was for staying alive. He was neither young nor old, and superbly fit. He stood tensed, like a lion ready to spring.

“Who dares enter my chamber?”

The reply was very soft and strangely accented, yet quite distinct. Not foreign, just odd.

“Read what is written. On your table.”

Still as ready to attack as a lion surrounded by hunters, Tigranes edged over to his writing desk and picked up a papyrus. He glanced at it sideways. In his copious spare time – for the life of a prince consists of waiting – he had pursued the arts somewhat himself and he could tell that the writing was tiny, ornate, and exquisitely executed, like something done by some master calligrapher hundreds of years ago. He had seen the like in the royal archives. Under other circumstances he might have paused to admire it.

“I can recite the story,” said the voice. “I know it by heart. But I think that you should either hear or read –”

“Why –?”

“It has immediate relevance to your situation.”

The prince whirled around again.

Now the voice was behind him. He turned again, but saw nothing in the gloom.

He picked up the papyrus and began to read, as the other recited word-for-word.

***

There was a man called Madatho, who was carried off by Death. Like all men in such circumstances, he protested that it was not his time yet, that he was afraid, that his wife and children would be left destitute, that he had things yet to accomplish in the world, and like all men he made these protestations without even the most forlorn hope.

Yet he was granted a reprieve. That is the extraordinary thing. That is why his story is worth telling.

This Madatho had heard something crawl up out of the river onto his porch, in that late hour of the night when no man of Reedland is ever abroad. For three nights the thing paced back and forth, in heavy, ungainly steps, not like a man at all, but like some heavy animal unsuited for walking on land.

For three nights, from the forbidden hour until dawn, it whispered his name in a hissing voice that did not sound at all human.

At last, when he could bear the terror of it no longer, when he was certain that his doom was upon him, Madatho flung open his shutters and found himself face-to-face with a gaping-jawed crocodile. The thing poured over his windowsill and stood up before him like a man, for it had the pale, bloated, naked body of a drowned man, though with the head, claws, and tail of a crocodile; and Madatho knew that this was Death come upon him, for it was one of the evatim, a messenger and servant of Surat-Hemad, the God of Death, whose teeth are the numberless stars, whose mouth is the night sky, who shall at the end of time devour the entire world.

He made his useless pleas, as all men do, and, to his astonishment, the creature said to him, “My master requires a service of thee. During the time spent in the performance of it, thy life shall be spared.”

Madatho babbled on, “Yes, yes, anything –“

The monster told him that he must travel five hundred miles downriver to the City of the Delta, and there announce to Nakamaenon, the great and terrible king, that his life had been weighed by the Lord of Death and found wanting, and that he and all his dynasty were to become extinct.

Madatho was terribly afraid, but he could hardly refuse.

“Come then,” said the monster, and it took him by the arm and hauled him out the window, across the porch, and down a ladder into a boat. Madatho wanted to protest that he needed to see his wife and children one last time, that he should pack something for the trip, that he needed money, but he knew that his first set of useless excuses were more than enough.

What followed was like a dream. There were subtle transitions, as if he’d closed his eyes and opened them again in another place, in another situation. It seemed that the Moon was high in the sky, motionless, a thin, sharp crescent, like a knife.

The monster was transformed into a kindly old man in a flowing robe. “You can call me Uncle,” he said. Uncle pushed the boat along for a time with a pole, but then they were in deeper water, and the vessel was larger, propelled by twenty oarsmen – who had crocodile heads at first, then human ones – while Madatho and his uncle sat in comfort beneath a canopy.

As the river slid by, they discussed philosophy, and his uncle told him the secrets of the waters and of the skies, and taught him to read the secret language of the stars. Therein Madatho read this very tale, and knew his own destiny.

They tarried on their way to the Delta, stopping in all the towns and cities along the way, trading for goods, losing themselves in houses of pleasure for weeks or even months at a time, but always at night, as the knife-like Moon remained unmoving in the sky, and the stars, which are the teeth of Surat-Hemad, gleamed.

All his enterprises prospered, and Madatho became rich, being directed in all things by his wise uncle.

Only on a few occasions did Madatho awaken suddenly, as if from some astonishing dream, torn in conscience, filled with fear. He knew he could never return upriver, but he managed to send letters and money home to his wife and children.

Yet he had read his own tale in the stars.

Still onward he drifted, downstream, and the boat with the twenty oarsmen became a great barge of pleasure and of commerce, a floating palace, which was anchored for a full year at the City of the River’s Turning, where Madatho took from his concubines another wife, and begot a son upon her. He built a golden tower for her in the river’s bank, connected to his barge by a ramp, across which he would go every night to lie with her.

It was almost possible to forget his ultimate mission, but he did not forget. His uncle was always there, to whisper in his ear, and when he did, Madatho would grow silent, and sometimes weep.

His uncle taught him magic. He became a great wizard, learning to speak to the spirits of the air and to command them.

People came to him to hear him prophesy. He was their oracle.

It occurred to him to wonder whether any of this was actually happening, or if he might still be on the porch of his house far upriver, in the arms of a messenger of Death, dying slowly and horribly, and hallucinating everything else as his mind shut down.

“Does the fly, caught in amber, dream of all eternity, or does it experience but a single instant forever?” he asked his uncle.

“That is an interesting question,” said the other.

Suddenly Madatho felt a great desire to run into the golden tower, to embrace his wife and look upon his infant son, to reassure himself that they actually existed.

“Alas, we are drifting,” said his uncle.

Not even his magic could change the river’s flow. His tale was long and leisurely, but it was not written to go on forever. In his heart of hearts he knew that.

The barge had broken loose from its moorings. He looked back just in time to see the golden tower vanish behind the curving, dark shore, beneath the knife-thin, crescent Moon.

At last he came, as had been prophesied, to the City of the Delta, and with great ceremony he stood before Nakamaenon the king, and delivered the message.

Whether he did so out of pride or hopeless resignation is uncertain, but he did deliver it. All that is reported is that he spoke softly, and his manner was dignified.

With a wave of his hand, the king caused Madatho to be hauled into a dungeon, tortured hideously and exquisitely, then crucified.

All this while he cried out for his uncle, who was nowhere to be seen.

It was only as he hung on the cross, in his last extremity, that his uncle stood below him. Now his uncle’s face was that of a crocodile again, and the hands folded before him were claws.

Madatho screamed at him, every obscenity he knew.

“Ingrate,” said the crocodile-thing. “You were given a substantial reprieve, in which you gained riches and knowledge, knew pleasure and happiness and even sired a son to carry on after you. Furthermore, do you see that fire in the distance? That’s the palace burning. The people rose up against the tyrant, inspired by your defiance. You are their hero, their liberator. You have gained your revenge. In the future you will be worshipped as a god. What more can you ask?”

“Somehow none of that comforts me just now,” Madatho said.

***

Tigranes chose to be amused. He chose to laugh.

“This is a fable. My forefathers overthrew Nakamaenon more than two hundred years ago and established our dynasty –”

“I know. I was there.”

The voice came from off to his left. He turned again. If the speaker was actually moving about the room and not casting his voice, he moved with absolute silence.

“Show yourself!”

“Here I am.” Now the speaker was to his right. For once, he saw motion. Someone stepped silently in front of a curtain, half-visible in lamplight. For a moment the prince stepped back and stared, astonished, for he had expected a formidable-looking opponent, or even one of the crocodile-headed evatim, but what he saw before him was – a child, a boy, maybe fourteen or so, with an unkempt mop of hair, a round, smooth face and strange, dark eyes; raggedly dressed, in a none-too-clean tunic and loose trousers torn off at the knees. The reason he had moved about silently was simply that he was barefoot and very thin. He must have weighed almost nothing.

The prince’s first thought was that this was a joke, that this rogue was a beggar from the street turned burglar, attempting to use a remarkably original method of talking his way out of a tight spot – but it did occur to him that the boy showed no trace of obsequiousness, and did not bow before him or address him as “Lord” or “Majesty” or even “Sir.”

For such impudence, the least he would do would be to have the brat soundly beaten.

But then he noticed that the boy’s bare legs were criss-crossed with faintly glowing scars, and there were more such marks on him, on his bony chest and sides, visible through his threadbare tunic, which was several sizes too large for him and open down the front. That gave the prince pause, but only for a moment.

“And what am I supposed to call you . . . Nephew?”

“I am Sekenre,” the boy said. “I am as I seem and I am not, for I have many souls. I am a sorcerer who has lived for . . . considerably longer than you might think. This is not a joke. I have come to you –”

“Yes, why are you here?” demanded the prince, pacing nervously back and forth, twirling his knife. “To murder me on behalf of one of my numerous brothers? To carry me off into the night? Are the gods are running short of crocodiles –?”

“Because we have interests in common, you and I shall go on a journey together.”

“Is that so?” snapped Prince Tigranes, who, quick as a striking snake, turned and hurled his knife at Sekenre.

But the boy was not there when the knife arrived. It bounced off a marble pillar and went clattering into the darkness.

***

When he awoke the following morning, Prince Tigranes was still angry.

Yet there was no time for that. Precisely because his dynasty, whose grip on power was not all that certain these days, was foreign, descended from conquerors from across the sea, the court observed all the ancient rituals of Riverland with stupefying faithfulness.

At dawn, eunuchs came for him, clucking in their warbling voices that reminded him of so many pigeons. He allowed himself to be bathed and dressed, to have pins placed in his hair, jewelry on his hands, arms, and ears, great golden bands draped over his chest until he was practically armored. Someone painted his face, drawing black streaks back from his eyes, powdering his cheeks, coloring in his lips.

There were prayers and ritual prostrations, performed in shadow, and again once the curtains had been drawn, in the light of the newly risen sun.

He didn’t get any breakfast. There would be a ritual feast later on, at which nobody ate anything. He barely had a chance to examine the pillar where his knife had struck the night before. There was a scratch. His strange interview had not been a dream. For that matter, the papyrus still lay half-curled upon his desk. He was not able to search for the knife he’d thrown – no matter, for he had secreted several more about his person – before he was hurried into the main palace, to appear on the balcony overlooking the great forum of the City of the Delta where the masses of the people waited in silence for the obsequies of the late king, Wenamon the Forty-Second, to begin.

Now he and his too-numerous brothers and half-brothers, all fourteen of them, raised both their hands in the prescribed manner. All of them stood in their silver robes, marking them princes of the blood, weighted down in their golden ornaments, their faces hidden behind masks of the Holy Sun – silver masks because no prince could wear a golden robe or a golden mask or the beehive-shaped crown, which were for the king alone.

In unison, they lowered their hands.

On this signal a great moan rose from the crowd. More enthusiastic common folk began to dance around the royal coffin and flagellate themselves in grief, joined by some of the eunuchs and junior priests.

It was all great fun, Tigranes thought to himself. Defunct kings were the sport of the city, the reigns being short these days and usually given to abrupt endings. All modern kings took the name of Wenamon, after a great ruler of antiquity, as if they hoped to borrow some of the other’s glory; but it wasn’t working. This latest Wenamon had accumulated far too many wives, concubines, and offspring, grown fat and lazy and completely oblivious to the condition of the realm, where the treasury was empty, the oracles offering only bland reassurances, and corpses of murdered citizens from sacked cities upstream kept floating by, sometimes in clumps of hundreds, to the tsk-tsking of soothsayers and ministers – and then he managed to prick himself on a poisoned needle, so the story went.

Or maybe the gods just struck him down out of boredom, to speed the game along.

The fourteen princes stood on the great, curved balcony, their robes flapping in the wind like gorgeous banners.

At least the morning breeze was cool. Later on today, it would be sweltering.

Tigranes realized he had to piss. There was nothing to be done. He would endure, as he endured so much more. Hours passed. The ritual feast came and went, and only the ghosts of ancestors, allegedly called back for the occasion from the Land of the Dead to inhabit the great sarcophagi that lined the feasting hall, were satisfied.

Then the doors to the palace were closed, and the more secret, sacred part of the rites began. (In the dark, behind a pillar, Tigranes managed to relieve himself.)

After hours more, at the very last, a solemn procession descended by torchlight down countless stairs into the vaults beneath the city, where the Black River was, that river which flowed in the opposite direction from the Great River of the waking world, not out of the Crocodile’s Mouth but back into it – for Surat-Hemad, whose teeth are the stars, disgorges all living things into the world, only to swallow them up again. Here the dead king would begin his final journey into the afterworld upon a barge made of reeds.

Here, too, he would speak, and name his successor.

Everyone was masked. The princes all wore their solar masks. The priests and attendants wore masks of apes and fish and birds. The air was thick with smoke and incense. The procession came to the border of Leshé, the realm of dream, where sometimes ghosts mingled with the living, and sometimes the animal-headed figures glimpsed among the others might not be courtiers at all, but gods. Indeed, Tigranes thought, if everyone is masked, how does anyone know it’s really them?

The stone floor gave way to mud. Everyone’s boots and sandals made sucking sounds as they walked, except, Tigranes realized, the small, slightly-built person beside him, who took him by the hand with unseemly familiarity.

“Nephew?” he whispered.

The other squeezed his hand in reply.

The hand that held his was small and smooth, and such of the thin forearm as was visibly criss-crossed with glowing scars. He saw a dark robe, decorated with heron designs, and a bird-mask, and he had the impression that the other was walking barefoot across the surface of the mud without sinking, like an apparition on the surface of water.

It amused him to allow this other, this Sekenre – wasn’t that a name from an ancient book? – to remain. He realized, too, that he was more than a little bit afraid, surrounded as he was by ghosts and gods and thirteen brothers who wanted to murder him, and it was some comfort to know that at least one person present was an honest impostor.

He couldn’t tell his brothers apart, except for the youngest, Afkeraton, who was a hunchback and a cripple and moved like a scuttling crab.

Now came the solemn climax of the ceremony, after the late king’s coffin had been placed in the reed boat that floated in the black water. The high priest bade all fourteen princes mount a little gangplank and climb into the reed boat, and there lean down over the still-open coffin of their father, where the corpse lay, wrapped in scented linens, covered with amulets, and wearing a golden mask, through which the dead man’s spirit would speak one last time and name his successor.

With fourteen princes, it was a delicate matter, getting them all into the boat and properly arrayed without capsizing. Soldiers and attendants waded into the water to assist, to steady the boat, but only the princes were allowed into the boat itself.

Tigranes had lost track of Sekenre.

He looked around, and saw the impassive masks his brothers. He noted that the deformed creature Afkeraton seemed to hang back a little from the others. No matter. How could that thing possibly wear the beehive crown?

The air was thick with incense and smoke from lanterns and torches. Tigranes saw, drifting in it, not a few ghosts, and perhaps even an occasional god. Something with the face of a crocodile and glowing red eyes opened its enormous jaws right across from him, but then vanished, the way a shadow does when a curtain is shifted.

Drums beat. Horns blasted. There was one rattle from a bronze sistrum, and then utter silence.

The princes leaned forward, even Afkeraton. The open mouth of the golden mask seemed to widen, becoming a black abyss. There was a faint whistling, like wind. Only after a minute or two did Tigranes realize that something was wrong. Black, oily smoke rose from corpse’s mouth. At first it was just a wisp, but then a great cloud, as if from the chimney of a furnace where the fire has been suddenly stoked to life — and all erupted into chaos, everyone gagging and choking, screaming and shouting as someone beat uselessly on a drum.

It felt as if burning tar had been poured into his lungs. Tigranes turned and leaned over the side of the boat, heaving. Others tumbled around him, headfirst into the water. He saw corpses floating there, soldiers, attendants, priests, princes in their silver robes.

He thought he saw Afkeraton scuttling down the gangplank, but he couldn’t tell. He couldn’t see clearly. He couldn’t think. Then someone had him by the hand, and pulled him over the side of the boat into the water, and he was floundering in knee deep water and mud, almost blinded by the smoke, and everything else was just an impression, like a dream he’d been hurled into, all confusion, swirling shapes.

He had the sense that Sekenre was with him, dragging him away; but he stumbled, fell to his knees, and his wet robe and the mud seemed to be dragging him down. Then someone was blocking their way, someone or some thing that rose up out of the water, huge, draped in wet cloth and mud, eight, ten feet tall, like a bundle of logs or a pile of stones somehow came to life in the vague semblance of a man. This thing wore a mask, like of burnished silver, like a snarling hyena, and rimmed in pale fire.

Behind it, Afkeraton cringed, clutching the stolen golden mask from their father’s corpse to himself, and pointing and laughing while some kind of combat took place. Sekenre had produced a knife or a short sword from somewhere and blocked blow after blow from the giant, whose weapon seemed to be a glowing crescent. Tigranes couldn’t see it clearly. But the contest only lasted for a few seconds. Then the giant or whatever it was reached out with its other hand and merely touched the boy and sent him crashing into Tigranes, and the two of them tumbled backwards, sprawling, splashing, choking in the mud and water, in absolute darkness.

Then there was no sound at all but the dead king’s ghost, wailing in protest as the black, poisonous burning consumed its body entirely.

Again, silence. For an instant, strange stars seemed to appear, but they were eyes and teeth; and all around them the evatim, crocodile-headed things with the bodies of drowned men rose out of the water to devour the dead.

Tigranes couldn’t breathe. His lungs were burning. The air was still thick with the overwhelming stench of foul tar and he was sick from it. Then he was aware that Sekenre was trying to get him to do something, and he got the idea, and somehow he’d removed his heavy, jeweled sandals and thrown them away, and then he found that he and the boy both could walk on the surface of the water as if on a cold, marble floor. The two of them clung together and staggered away. He didn’t know how long he went, half stumbling, half running. He felt terribly weak. His lungs burned. He had a sense of crashing face-first through reed and small branches.

It was only much, much later that his lungs and vision both started to clear, and he could almost think again, and he realized that he was in no vault beneath the city, but outdoors, in the midst of a vast reedy swamp; that he and the boy were walking on the surface of a black river; that the Moon overhead hung motionless and crescent-sharp like a curved sword; that the stars were few, far between, and dim, and the constellations they almost reluctantly formed were utterly unfamiliar.

He wasn’t in the living world at all, he realized. This was the realm of the dead, or nearly so. He tried to recall what he’d read about this, what he’d learned from learned men when he’d questioned them, what sometimes even the priests let slip: that there were three supernatural realms, each progressively further beyond the world of living men: the first of them Leshé, or Dream, the second Tashé, or true Death, and the third, Akimshé or Holiness — this last being the domain of the gods and a very few blessed savants who reached there on spirit-journeys. But as sorcerers are decidedly unholy, being servants of the Shadow Titans whom the gods fear, not of the gods, it was very unlikely he would be looking upon the divine country any time soon. Whether sorcerers are entirely evil, depraved beyond redemption, or capable of at least morally neutral action depends on your philosopher, what books you read, on hearsay – and his head was much too muddled to follow this train of thought further. The best he could do was breathe deeply of the damp, cool air and wait for the dizziness to pass.

In time he realized that the boy Sekenre was clinging to him quite feebly, and that in fact he more or less dragged the boy along in his arms. He paused. Sekenre still wore a bird mask, but it was smashed, so Tigranes tore it off and tossed it aside.

Sekenre’s face was pale. His eyes were rolled up so that only the whites showed. There was blood trickling out of his nose and from the side of his mouth.

Tigranes realized that the boy was soaked, not in water, but in blood. His heron-gown was dark with it.

Now the cool air made the prince’s mind very clear indeed.

The thought came to him, Why do I need this child at all and why should I trust him? For half an instant he considered just tossing Sekenre aside and going on, but his reason got the better of him. Going where? He was lost here. Even if he could reach the City of the Delta again, he had few prospects there. His youngest brother, the scuttling freak, had outsmarted them all and doubtless seized the throne for himself.

Possibly, as Sekenre had seemed to imply at their first meeting, he and the boy had some interests in common.

Therefore what he did was gently take the boy in his arms. Indeed, he didn’t weigh very much. Tigranes found that as long as he held Sekenre, he could continue to walk on the surface of the water, but as soon as he laid him down gently on a little island made of tufts of grass, he sank almost knee-deep into the mud. He crawled up onto the grass beside Sekenre and examined him as best he could in the dim light, tearing away his ruined gown and the ruined tunic under it, observing that scattered across the boy’s bony and so frail-seeming body were a multitude of faintly glowing scars. But more by feel than sight he discovered a puncture wound in the left side of the chest that was indeed bleeding quite a bit. The whole area was slick with blood, and Tigranes’s fingers came away sticky.

He tore a strip off the boy’s robe and bound it around him, to staunch the bleeding, but he didn’t know what to do next. Such knowledge of medicine as he had was all about spirit flows and balancing of the humors, and was entirely theoretical.

He couldn’t tell if the boy was still breathing, but took the fact that the marks on him continued to glow as a sign he was still alive.

After a while he nudged his shoulder gently, and much to his surprise Sekenre coughed and opened his eyes.

“ . . . unplugged me . . .” he mumbled, spitting out blood.

“What?”

“We sorcerers are a quarrelsome lot. We fight . . . strange wars . . . many wounds, which we can repair with magic fire.”

“Can you . . . repair this one?”

“If we are not in immediate danger, it is better not to.”

“I don’t understand.”

“It’s like putting a plug into a barrel. Somebody can take it out again. Each wound is a vulnerability, if an enemy can discover it. It’s best to try to heal naturally, if you can. But you never can . . . not all the time.”

The boy closed his eyes and was drifting off again.

Tigranes nudged him one more time. “What happens if you die?”

“If I die, then my soul, and all the souls of those I have slain, which reside within me, awaken inside the mind of the one who has killed us. His name is Iod. He is very old, thousands of years, and very evil. Right now he is your brother’s guardian, but I do not think . . .” Sekenre sighed and gasped for breath and spat out blood again. “I don’t think his intentions are entirely what your brother is hoping for.”

Now the boy seemed to lapse into a delirium, in which he babbled in a variety of voices and languages, and as Tigranes sat there beside him in the dark, the prince came to truly believe what he’d only regarded as rumor before, that sorcerers are composite beings, who gain their powers by killing and absorbing one another. He was willing to believe, too, that sorcerers do not age physically, and he wondered if what Sekenre had really survived as long as he seemed to imply. There was, in old books, a story about a boy-sorcerer of that name who may have been responsible for the death of Wenamon the Fourth – allegedly by lifting his still-beating heart out of his chest — almost a thousand years ago. The practice of naming all kings with the great name of Wenamon had only been revived in the previous dynasty, about three hundred years ago. That this “boy” might be in the habit of killing kings did not recommend him . . . or perhaps it did, for certainly if the now no doubt crowned “king” Afkeraton, otherwise known as Wenamon the Forty-Third, could be disposed of by such picturesque means, Tigranes would have no objections.

Indeed, he and Sekenre might yet have interests in common.

He could only sit there in the dark and wait for something to happen. He could only review his life to this point, who he was, what his ambitions were, how he had intended to live his life. He could only shake with rage when he realized that the hideous, ridiculous Afkeraton had snatched everything from him so quickly and deftly.

He drew his knees up and rested his head against them, trembling with both cold and with anger. He felt exhaustion and pangs of hunger, but he was a strong man and could endure. After a time he seemed to fall asleep, and to dream, and in this dream he was able to wonder whether he was awake or not, and he could look back at the tale of his life so far without being able to tell where the dream began, or if it ever ended. Indeed, to the end of his days, he would never know, and he knew now that he would never know, as if he had come adrift in time, and past and future were all part of the same stream. Adrift . . . as the current carried him, as it carries all created things, back to the ultimate source of both life and death, which is the belly of the Devouring God, Surat-Hemad, whose mouth is the night sky, whose teeth are the numberless stars.

Here, under the fewer, dimmer stars of the deathlands, he dreamed, and awoke within his dream, or dreamed that he had awakened.

There were ghosts with him, there on the little island. He saw pale faces among the grass, and drifting shapes like mist. He saw some of them gathered over the sleeping Sekenre, and they spoke to the boy in a language Tigranes did not know, but recognized, as the universal language of the dead, which is spoken and understood only by corpses and ghosts, by sorcerers, and by the most profound of sages.

Once or twice Sekenre made some brief reply, in that same tongue.

Then, as the dream or the awakening progressed, the sky lightened just a little bit, not into a sunrise, but more as if a second, full moon were about to appear. But it didn’t. The knife-crescent remained where it was. Perhaps it brightened a little and the stars dimmed, or else his waking (or dreaming) eyes adjusted.

Time passed. He did not know how much, but perhaps a great deal, if there was such a thing as time in this place.

Someone touched him on the shoulder. He looked up and beheld a maiden there, clad in a gown the color of moonlight, her hair long and pale, her face exquisitely beautiful and, perhaps, slightly glowing. (Or else that was a trick of the eye.)

She bade him get up, and he got up.

He demanded her name and she said that it was Tsais, and that she dwelt on a barge with her father, Yazdigerd.

“Is he a sorcerer, then?”

“No, a philosopher.”

“How did you find me?”

“Your friend called me.”

“My friend . . . ?”

Tigranes looked down at Sekenre, then back at Tsais, who had turned away, as if to leave. He bent down, picked up the boy in his arms, and carried him, ready to walk again on the surface of the black water, but then he saw that Tsais had a boat. She bade him sit in it, and he sat, with Sekenre limp in his lap, while Tsais stood at the back of the boat and drove it through the water by slowly moving a single oar from side to side.

They slid through the black marshes, amid the mist and softly whispering ghosts. More than once he saw what he first took to be crocodiles, but knew to be evatim, lying in the water, watching the boat as it passed.

Then he saw what he first thought was a rising moon ahead, but it was not. It was a barge, hung with lanterns.

Silent servants in masks tossed them a rope and helped them aboard. While Tigranes was already too benumbed with wonders to question anything anymore, he did notice with some disquiet that the servants were all hollow behind. Their bodies were open at the back. They were like sails, filled with wind; made of air, and there was no wind.

After Tsais had directed him to leave Sekenre upon a bed in a cabin, where the servants would care for him, he was introduced to the philosopher Yazdigerd, who proved to be a short, stout, bald man who looked more like a clerk or a wine-merchant than a philosopher.

Yazdigerd laughed about this. “Well, what is a philosopher supposed to look like? Long hair and beard, long gown, a grave manner?”

“Yes, I suppose so,” said Prince Tigranes.

The other shrugged and motioned for the prince and for Tsais to sit at a table on the deck.

“Sorry. What you see is what you get.”

“Is it?” said the prince. “Is it ever?”

“An interesting philosophical question, as we philosophers like to put it.” Then he leaned forward, and his manner changed, as if to say but all joking aside, and added, “But more importantly, remember that what you have is what you’ve got.”

The servants brought them food and drink, a fine banquet, of genuine food from the earth of living men. As Tigranes tasted the meat and sipped the wine, “How can we know that any of this is real?”

“Are you less hungry after you eat?”

“How can I tell?”

“How can we tell anything? Perhaps were are all being slowly digested in the belly of an enormous crocodile who has devoured the world, and our entire lives from birth to death and beyond are all an illusion.”

Tigranes took a piece of bread and bit into it.

“What we have is what we’ve got.”

“Precisely.” Yazdigerd turned to his daughter. “Don’t you agree?”

Tsais said something Tigranes could not quite make out.

“Don’t talk with your mouth full, dear.”

***

So it was that Tigranes, who had been prince of the Delta and had aspired to be king of all Riverland, came to dwell in Leshé, the country of dreams, which is on the borderlands of Death. Benumbed as he was to all wonders by now, he nevertheless learned much, and came to understand how one can inhabit the country of Dreams, how philosophers and sages reach there through stern discipline and exercise, and how sometimes the most unfortunate wretches find their way there too, as an escape from their miseries.

“I could well be,” said Yazdigerd, “not a philosopher at all, but some petty official cast into a dungeon for an offense, and left there to rot, all the while dreaming that I am here, on this barge, on this river. Or it could be that I am on the barge, dreaming I am in the dungeon. Sometimes I have that dream. It disturbs me. I endeavor to awaken from it as quickly as possible.”

Yazdigerd was not a Riverlander at all, but came from a country far to the east, where the king’s rule was strict and harsh, and any number of petty officials wound up in dungeons.

For an indeterminate time, they drifted on the black river, beneath the crescent Moon and pale stars, into realms Tigranes had never imagined existed. Yazdigerd traded for rich goods in cities of pale white stone, where not all the folk were human, but many had the heads of birds and beasts. The two of them became fast friends, and adventured together in the black mountains, in the night regions beyond the river’s edge, and hunted fabulous beasts there, including one monster, whose bones were only known on earth, but here quite alive, so large that once, in remote antiquity, a king had caused one of the creature’s teeth to be hollowed out and serve as a royal warship.

When that king died, Yazdigerd explained, he sailed into death in that vessel, which is why no such thing has ever been seen in the world since.

Sekenre’s wound slowly healed, and he eventually joined them in their philosophical discussions. Someone had either repaired the boy’s robe or provided him with another one. Now he was always clad in ankle-length, dark gown, embroidered with herons. He went barefoot, moved absolutely silently, and could walk on water. Sometimes Tigranes spied him stepping over the side of the barge, and vanishing into the darkness and distance. Sometimes he saw him, far away, conversing with ghosts, or with the evatim, and looked on him with certain dread when he did this, but again he reminded himself of the philosopher’s advice, What you have is what you’ve got, and he realized that Sekenre had never harmed him, and that he and the boy might indeed still be allies.

But this was a cause of unease, that he did not know what Sekenre was truly thinking; that he could not hope to comprehend what the boy was thinking, or planning; nor could he ever learn all that Sekenre could learn.

He watched with fascination as Sekenre produced a book from somewhere and wrote in it, in that same intricate, beautiful script which he had seen on the papyrus the first night. But he couldn’t read it. The boy let him turn the pages, which seemed to go on forever. It was some kind of illusion, or magic. The book was not very thick, but its pages seemed infinite.

Sekenre smiled at him, in that odd, solemn way of his, which was very much like the manner of a child who could not quite explain something. “I can’t read it all either, but I think that someone within me can.”

For the most part Tigranes allowed himself to be lulled into the state of things as they were, remembering the philosopher’s advice, and he watched the dark shore pass by, and he wondered at the sights he saw. Once, he, Yazdigerd, and Sekenre together walked into the air and came to the Moon, which appeared before them as an enormous crescent, like a vast sword. They approached from behind, out of the shadow, and stepped into the sunlit country of the Moon and there saw golden hills and golden rivers, golden towns, golden people and golden gods. They gazed down at the Earth from there, and saw how tiny it looked, how slightly absurd, like a blue marble a child might roll in a game.

But it was in Leshé, in the darkness of the river of dreams, that the real miracle occurred. Tigranes found himself spending more time in the company of Tsais, his host’s daughter, and he made excuses to converse with her; and before long he felt stirring within himself such emotions as he had never before known.

In time – though there is no way to determine time beneath the motionless crescent Moon and pale stars, in the country without sunrise — they knew that they loved one another, and he took her to wife. Then for a further time, which might have been a fleeting instant, or years, he dwelt with her in a golden tower by the shore of the river, while her father’s barge was moored there; and he had a son by her, who was named after a sage of her father’s country, Vahran; and still they lingered in perfect happiness while Vahran grew until he was almost as tall as Sekenre.

Then Tigranes asked his wife one night, as they lay in bed together, “Is any of this real? I’ve dreamed that I was a prince in another place, whose brothers tried to kill him, who was wronged and cheated out of kingship, and whose whole life had been a matter of subtle waiting to kill or be killed. But, am I the prince dreaming I am as I am now, or am I as I am now dreaming I am the prince?”

“I have no idea,” his wife says. “Father likes to chew on that sort of thing. Don’t let it bother you. Go to sleep.”

***

Tigranes’s undoing came from a specific cause, which is why it is worth telling.

He could not put the thought from his mind. Then his son asked him one day, “Father, who are you really?”

Tigranes joked and said, “An interesting question. I am myself.”

But another time his son said to him, “Father, who are you?”

And he said, “I’m . . . not sure. Don’t let it bother you.”

Then, realizing he wasn’t getting anywhere, his son said to him, “Father tell me a story of who you once were,” and then it all came pouring out of him, and he spoke of Riverland, and of his depraved, incompetent father, Wenamon – whatever his number was; the prince couldn’t remember at the moment – and his thirteen brothers, including the scuttling freak, Afkeraton who had seized the throne through blasphemous murder. As he spoke, he trembled with rage, and unconsciously felt about himself to see if he still had any throwing knives concealed on his person.

When he had told a considerable amount of this story, Tigranes wept, and Vahran, frightened at what he had done said, “It’s just a story Father. I don’t need to hear any more of it.”

But it was too late. Weeping still, Tigranes left the room and the tower. His wife Tsais encountered him, and he turned from her, weeping. He encountered his father-in-law, the philosopher Yazdigerd, said to him, “Consider what you have. Think only on that.”

“I can’t,” Tigranes said. “I’m sorry, but I can’t.”

He left the tower. He walked along the golden gangplank onto the moored barge.

There Sekenre sat at a table, playing the game of ma, which involves moving black and white stones across a board. It usually takes two players, but the boy seemed to be playing it by himself.

“I have to go back,” Tigranes said, weeping, trembling with rage. “I have to settle things.”

“Ah,” said Sekenre, moving one black piece. “I fear we have broken adrift.”

The prince looked back once to see the golden tower vanishing around the dark curve of the river.

He saw that they weren’t in the barge at all, but in a reed boat, and a charred one at that, which stank of poisonous tar. But it floated. It would do. They drifted in silence while Tigranes thought harsh thoughts, considering all he had learned, making his plans, like a player of ma thinking out his campaign many moves in advance, all the while revealing nothing by his face or his actions.

Then there was no boat at all. Perhaps it sank or they stepped out of it. He and Sekenre walked barefoot on water, then on mud, then they came to a muddy shore in a chamber far underground. From there they followed a corridor, ascended many flights of stairs, and, miracle of miracles, emerged into a courtyard beneath a full moon and multitudinous stars.

He had not seen a sky like that in . . . years. He paused at the wonder of it, but only for a moment.

There were gibbets set up in the courtyard and empty corpses dangled from them, devoid of their ghosts. The façade of the palace looked to have been burnt and only partially rebuilt.

The great bronze doors opened at Sekenre’s touch. No guards came to stop them. Perhaps they were invisible, or time was somehow, still suspended. Sekenre made fire with his hands, and held out a flame on his outstretched palm, and lighted their way with it.

They ascended more stairs. They traversed corridors and galleries. They saw statues everywhere of beast-headed and bird-headed creatures, and encountered such creatures in the flesh; and humans too, most of whom moved about fearfully. But no one seemed to notice the two intruders.

They came to what Tigranes knew to have been the royal bedchamber of the kings of the Delta since time immemorial.

Within the canopied bed lay his brother Afkeraton, now and for many years also known as King Wenamon the Forty-Third, who sat up astonished when the doors to his chamber slammed open and Prince Tigranes entered.

The king was very old, white-haired, feeble, trembling.

“Your life has been weighed and found wanting and now must end,” said Tigranes.

“You . . . you!” The King pointed a trembling finger. “My brother Tigranes has been dead for seventy years! It cannot be!”

“Sometimes things are not as they seem, My Lord,” came an icy, utterly chilling, utterly inhuman, third voice from the shadows beyond the bed.

Tigranes, who was never without his throwing knives, even after so long, had gotten one out and was ready to slit his brother’s throat with it, drew back as an immense figure arose from out of the darkness, a thing with the face of a snarling hyena – it was not a mask this time, nor entirely, living flesh, but more like molten metal that was alive – and massive, ungainly limbs beneath its flowing robes like a body that was strangely designed, yet immensely powerful. This was Iod, a sorcerer far more ancient and powerful than Sekenre, and as a consequence in a considerably worse state of repair, with almost no trace of his original humanity left, every piece and aspect of him broken, repaired, replaced, made stronger, if less like a man.

Sekenre drew his short sword and faced off against Iod, who wielded a glowing, curved blade that looked like a slice cut off the Moon.

Unnoticed, Tigranes eased his way around behind Iod. This was all part of the prince’s plan. He’d thought this through.

But as it worked out, Afkeraton had a plan of his own, not to mention surprising strength still left in his aged, twisted body, for it was he who slid a gleaming blade of his own out from under his pillow and leapt from the bed, not at his brother Tigranes, but onto the back of the monster Iod. Afkeraton wrapped both legs and one arm around Iod, and with a stroke of the other neatly sliced off Iod’s head.

With a roar like an explosion, the gigantic thing that had been Iod the sorcerer collapsed into dust and fire, into swirling, tattered remains of cloth; and in that instant, because he had slain a sorcerer, King Afkeraton became a sorcerer, as the countless murdered souls and countless magics within Iod poured into him. His body writhed where he had fallen. His jaws snapped. His mouth foamed, spitting fire. His feet rattled against the floor in a series of wild kicks.

Tigranes, seeing what had happened, adjusted his stratagem instantly, and, before his brother could recover any control of his own body, drove one, two, three of his throwing knives into his brother’s heart, then slit his throat for good measure.

Blood splattered everywhere. Now Tigranes, having slain the sorcerer his brother had become, was himself a sorcerer, and a thousand outraged voices roared into his mind and a thousand years of magic and vile deeds and hideous memories poured into his mind like a vast avalanche, and he too writhed and coughed fire and was so distracted that it took him quite a while to realize that Sekenre had picked up the gleaming Moon-sliver sword and chopped his head off, but sealed the open neck with the fire of his hands, so that he – Iod/Afkeraton/Tigranes – wasn’t dead, just helpless, without a body. He had time to understand that Iod had been the terrifying tyrant who had made King Afkeraton his slave and that Afkeraton had long been looking for the chance to do precisely what he had done, but it took him quite a bit longer to figure out that because he wasn’t actually dead, the contents of what had been Iod were going to stay where they were, and not pour into Sekenre.

***

Indeed, Sekenre explained that to him later.

“It is more than I could handle,” the boy told him. “I – that part of me which is still Sekenre – would have been lost like a leaf borne away in a vast tide, and I would have become wholly a monster. I believe it is my great accomplishment that I have not.”

The head, Tigranes’s head, spat fire. “And whom did you murder, to become a sorcerer yourself?”

“To begin with, my own father. His soul is within me now, and it is his wish, too, that I not become, wholly, a monster. I try to honor him.”

Then Sekenre stalked out of the palace, and if anyone saw him, a barefoot boy in a dark robe, splattered with blood, carrying the still living but slowly burning head of a prince who had been missing for seventy years, well, enough bizarre and terrifying things had taken place in the City of the Delta of late that no one was about to question this one.

Out in the desert, Sekenre summoned the birds of the air, and they bore him up by the thousands, like a dark, swirling cloud with a single throbbing sphere of light within it, which was the burning head, and they carried him far out into unknown lands, where stood a haunted, immemorial city almost entirely swallowed up by the sand. There he climbed to the top of what had once been a bell tower, and using the pommel of his own short sword as a hammer and one of the throwing knives as a nail, he affixed the head of Prince Tigranes to a rafter by the hair.

The head screamed at him.

“You could have perished when your brother intended,” Sekenre said, “but you were granted a considerable reprieve. What do you have to complain about?”

For an instant, that which had been Tigranes predominated, and wept, and said, “All that is of small comfort to me now. Was any of it real? Did I really love Tsais? Do I really have a son?”

“Yes, and Tsais will mourn for you. Yes, too, you have a son, and when it is time I will bring him forth into the world, for his destiny is very great.”

The head spat fire. The voice was still that of Tigranes, but angry now.

“Was all this part of your plan? Did you plot this from the beginning?”

Sekenre got out his book, which he carried in a satchel around his neck, worn under his robe. He turned the beautifully illuminated pages.

“It’s all here, but I didn’t understand its meaning, until you showed me the way to the ending.”

The head screamed at him some more, in a stream of garbled obscenities and curses, in a hundred languages all at once. It was Iod. It was some monstrosity from within Iod. It had many other voices.

“When it is time,” Sekenre said, “perhaps in a thousand years, when I am ready to do it without becoming a monster, we shall resolve this. For now, you must wait here.”

He closed the book and put it away. He descended from the tower and walked into the desert. The warming sand felt good on his bare feet. It was a sensation he hadn’t felt in a while.

He sat down on a dune and watched the sun rise.

________________________________________

Darrell Schweitzer is the author of about 350 horror, fantasy, and (occasionally) science fiction stories. His work has appeared in TWLIGHT ZONE, AMAZING STORIES, INTERZONE, FANTASY TALES, WEIRD FICTION REVIEW, and many anthologies. His novels include THE WHITE ISLE, THE SHATTERED GODDESS, THE MASK OF THE SORCERER, and THE DRAGON HOUSE. He is an expert on Lord Dunsany and H.P. Lovecraft (and has published books about both) and is a former editor of WEIRD TALES (1988-2007). He has been nominated for the World Fantasy Award four times and won it once, as co-editor of WEIRD TALES. His 2008 novella LIVING WITH THE DEAD, was a Shirley Jackson Award finalist. Recently PS Publishing (UK) has brought out a two-volume retrospective of his best fiction, THE MYSTERIES OF THE FACELESS KING and THE LAST HERETIC (both 2020). He is also an active anthologist, having most recently edited THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS REVEALED (PS Publishing, 2019).

Andrea Alemanno is a compulsive illustrator who fills the line spacing, preferably at 300 dpi.

She’s from Italy and loves to move into a new city searching for inspiration. In every city, she constantly keeps drawing.

Now, 3 decades later (and a little bit more), she is still drawing and learning something new everyday.

She loves the traditional touch into a digital tools world so uses pencil, ink and digital colors to give life to her artwork.

Sometimes she shares her knowledge with wannabe illustrators.

Her work has been selected for several awards and she’s currently working for Italian and international publishers.