THE LINTON BANSHEE

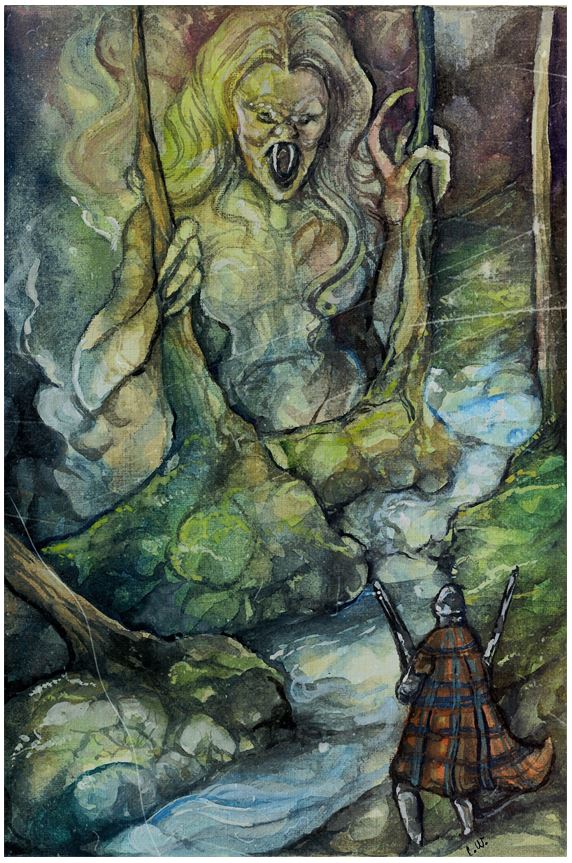

THE LINTON BANSHEE, by Rev. Joe Kelly, artwork by Karolína Wellartová

The sound started, quite suddenly, some ways off past the fields outside town, in the direction of Linton Hill: a wailing, ululating sort of shriek, yet not like any shriek that Conor Dubh had ever known an animal to make. It reminded him of a falcon’s cry, but also of a squealing mill wheel, of wind whistling through weathered stones; and there was something human in it as well, something that made the Irishman’s hair stand on end.

It shrilled for some time, and Conor followed its progress in the distance as it crossed the length of the great hillock, before at last tapering off as it receded into the evening.

He chuckled nervously, turned, and was surprised once again to see all the other men in the inn’s dining room had withdrawn to the bar, as far away from him as they could get in the small room. Conor was not a man who thought of himself as especially intimidating. Though fully six feet if he were an inch, he had something of the gentle giant about him: he was on the lean, lanky side of rangy, and the fierceness of his black brows was ever tempered by the quick Irish smile and light laugh that came even now. “The wind does make uncanny noises in these parts, eh?”

The others did not return his smile. An ever-simmering fear dwelt in those border Scots, born of countless generations of predation by reivers, and it still lingered near a century after those bandit clans had been extinguished. But just now, something had caused it to flare into a sharp terror that took their voices away and made them crowd together like their stringy cattle.

Conor sighed as he stood and walked over to the bar. He set his tankard down on the bar before the unmoving innkeeper. “Could use another before I’m off to bed.”

The inn owner glowered at him, dark and leery. “You heard it first.”

“Heard what?”

“You know what.” The innkeeper scratched at a mutton chop. “No wonder… you’re an outsider, a foreigner at that.”

Conor could already tell where this was going. A mysterious wail in the dead of night–of course he must be cursed now by some dread beastie. But he was also feeling peevish, at the superstitious foolishness of the villagers, and the fact that his cup remained dry. “’Fraid I dunno what you’re talking about, friend.”

One of the villagers spoke up in a hollow, haunted voice: “The She-Devil’s cry.”

Conor smiled. There it was. He turned on the villagers. “And what, pray tell, would this She-Devil’s cry be?”

Another spoke up: “The She-Devil of Linton Hill. The beast that’s haunted our village since time immemorial.”

Conor grinned from ear to ear. He whirled back to the innkeeper and slapped his palm on the bar with a bang that made the whole fearful crowd jump. “Another round, good man! There’s fine ghost stories to be told tonight!”

The innkeeper bristled. “You’ve got no cause for such childish petulance, mister O’Brien. The She-Devil’s no laughing matter.”

“Well, then, tell away, good folk!” Conor threw his arms wide, still grinning. “Frighten me to death! Tell me of this awful terror!”

“Can’t you see already?” A shrunken old man with bulging eyes bared his yellowed teeth at Conor. “She’s marked you, man! She knows you have no fear of her, she knows you have not made the covenant! And should you be lucky enough to live through the night, you should flee this place as fast as your horse’s legs can carry you!”

“Marked me? And how do you know?”

“The cry, young man. She cries thus when she means to kill a man, and it’s the man who hears her first who is to die.”

Conor shook his head and chuckled. “I see now. You’ve gotten your legends mixed up. That’s a banshee you’ve got there. But, you see, my friend, a banshee is neither a demon nor a murderer of men. Her howl only announces a man’s death, she doesn’t–”

The old man snarled, “I know what a banshee is, ya Black Irish bastard, and the She-Devil is no banshee! She’s a demon who kills men in their sleep, and every year she–”

“Keith!” The innkeeper interrupted the old man with a sharp look and words. The old man made a quiet noise of irritation, but said no more.

That was enough of the spooky tales and superstition for Conor. He rapped the bar insistently. “A drink. Now.”

The hunched old man nodded, his eyes fierce and grave. “Aye, stranger. Drink. Drink ’till you can’t stand. Drink, so that you might not remember what you see in your sleep tonight.” The old man stepped uncomfortably close, and hissed in his face, “That is, if you’re lucky enough to live to the morrow!”

Conor watched the old codger curiously as he shuffled off into a corner of the cramped dining room, glaring back at Conor the whole way, muttering to himself. Conor downed his tankard of bitter beer in one go and set it back down quietly. “Another.”

#

He was indeed drunk when he retired, but not so drunk that he did not forget to check that his arms were secured by his bed. He never let himself get that drunk, not on the road. His Scottish style claybeg and dirk, his large-bored musquetoon and two long cavalry pistols, marked him as a rogue, a mercenary, a hired killer, and he was obliged to keep all but the dirk hid while on the highways. Here, however, in the back country of border Scotland, he could wear them openly and proudly–and somewhat out of necessity as well, given the lingering danger of bandits, vicious and desperate pretenders to the reiver mantle. He collapsed at last into his stiff bed, and the weariness of the road and the beer united as a powerful soporific and sent him hurtling into a deep sleep.

Beyond the silent and shadowed fields, Linton Hill loomed over the village, a big, bald hillock, brooding and sullen.

As atavistic and ancient as Linton might be, that hill’s history was older still, and not merely in the sense of earth being old where Man were young. There was a history of weird doings on the Hill, of a time before time, before the first Celts drifted north into the British Isles, when an elder, darker race than they had spread over what would become Europe as the primordial ice retreated. There was a horror that lingered on that bald top, a hatred and a malediction upon the Hill that had long preceded the first Celts, a ward and warning against some awful, prehuman evil.

And there was something at the top of the Hill.

At a distance, it was merely a distinct and sharp feeling of fear and repulsion, some primal instinct which warned the curious traveler away, as the hoarse cry of the lion strums forgotten nerves of fear. But as one drew closer, it became plain that something stood atop the hill, something that glared malevolently back.

Its naked body was that of a woman’s, yet naught but the wide hips and a general, unplaceable sense of the primitively feminine gave this away, for it was so emaciated as to be otherwise unidentifiable as man or woman. Long, ragged hair flowed down its shoulders like the tangled vegetation of a fen.

And then, it drew its hands out from its silhouette–and they were not the hands of a human being. They were the three-fingered claws, gigantic and bone-skinny, of some inhuman species of monster that had haunted men’s nightmares uncounted ages ago, that had slipped unseen into the hide tents of the first peoples to murder them in their sleep and drink their blood. It had stolen babes from the cribs of mothers, relishing the fear as it did the blood which it feasted upon with impunity.

And it looked at him with hatred, brute hatred, for he did not fear it yet. But it would make him fear it, make him fear that it might taste the terror before it drank his blood in turn. And it opened its mouth unnaturally wide, and shrieked.

Conor woke with a start–the scream had been his own. His heart thrummed in his chest like the bass beat of cannon fire on a battlefield. He gripped at sheets soaked with sweat, and breathed deep and even to calm himself before his own fear killed him.

As he relaxed, he heard a timid knocking on his door. In a quaverous voice the innkeeper’s mousy little daughter called to him: “Sir?”

Conor replied breathlessly, “Aye?”

There was a sigh of relief. “I heard you cry out… are you all right?”

“I’m all right.”

“Do you need some fresh water, sir?”

Conor nodded. “That I do.” He lay back, and waited for sleep to return. After such a dream, it would take some time.

#

The innkeeper gave him an apprehensive look when Conor came down to breakfast the next morning. Though Conor did not relish the sight of the tasteless lard and beans, he was hungry, and so he was irked when the innkeeper hovered over his shoulder to ask him, “So, you’ll be headed on down the road, then, mister O’Brien?”

Conor shot him an irritable glance. “How’s that?”

“Oh, I didn’t mean to pry.” The innkeeper gave him an apologetically smarmy smile. “Only, I take it, by your… belongings, that a man of your… profession, whatever that might be, has most urgent… business, that will preclude him from tarrying, yes?”

It was not a difficult thing to cross Conor’s temper early in the morning, and the innkeeper had succeeded magnificently. Everything about him, his fawning airs, his obnoxiously sly and knowing words about business he knew nothing about, the fact that the bastard wouldn’t let him be to eat, everything pissed Conor off. And Conor Dubh was not a man to bed his temper back down easily.

He turned on the innkeeper with a nasty smirk. “On the… contrary, my good… man, my… business does not… require me to… hasten down the… road.” His smirk disappeared. “Now piss off. I’m hungry.”

The innkeeper’s smile, too, had disappeared. He drew up a chair and sat down with a thud beside Conor. Conor ignored his glare at first, and focused on muscling down the almost inedibly bland food and ignoring the grease from the lard that stuck to his throat and stomach like a film.

At last the innkeeper spoke up. “You’re a fool.”

“Hm?” Conor glanced up with a piece of gritty barley bread sticking halfway out of his mouth.

“A fool, I say. Any man who dreamed what you did last night would be a fool to stay here a second night–nay, a minute longer than he had to.”

Conor mumbled through his food, “And what would you know about my dreams?”

“I know you woke screaming last night. The whole house heard you. My daughter told me about how your sheets were soaked with sweat. And last evening we heard the She-Devil scream from the Hill. A man marked as you are, would be dreaming only one thing to make him cry out so.”

Conor waved him off. “T’was your damned spooky stories and your rotten beer–I knew it was off when I drank it.”

“My beer don’t enter into it, man. You ought to be damned thankful that the She-Devil did not kill you in your sleep last night. And had you any sense, you would make damn sure you’re as far away from Linton and the Hill by tomorrow night as you can get. And you would stop at the first church or chapel or cross you see, and thank Christ you’re alive to escape her!”

Conor took his time to swallow the mouthful of bread. “First of all, my good man, my prayers are my business, and mine alone. And second of all, I’ve no plan to leave Linton anytime soon.”

The innkeeper leaned over angrily. “If I have to kick you out of my inn to get your fool ass to leave Linton, I will. I’ll not have you threaten–”

Conor’s fist slammed down on the table with explosive force. Everyone else in the cramped dining room fell dead silent, and eyed Conor with the furtive glances of frightened hounds. The innkeeper sat back, looking a good bit more wary of the giant Irishman than he had been a moment ago.

No more smile tempered the ferocity of Conor’s black brows or his hard blue eyes as he fixed the innkeeper with a cold gaze that carried on it the promise of death, were he pushed a little further. “I’ll stay here as long as I damn well please.”

There was a brief struggle of wills as the two men stared each other down. At last the innkeeper looked away, his face sullen.

Conor nodded. He stood, and grabbed the rest of the bread. “I’m going for a walk. This place is too damn stuffy. Kills my appetite.”

He could feel the innkeeper’s eyes bore into his back as he left.

#

A brisk walk through the fields and up Linton Hill brought his appetite back with a vengeance. He was just finishing the last of the barley bread when he came to the top of the Hill.

He had been unsure what drew him to the hilltop until he was there. It was that damned dream; something about it lingered in his memory. Its vividity, perhaps. In any case, he hadn’t expected to actually find anything there, just some windswept heath and a nice view.

He was surprised, then, to find the time-mottled menhir.

It seemed oddly lonely, that little pillar of rough-hewn rock. It was not large, little taller than Conor himself; nor did it have other stones to keep it company. It might have easily fallen over, or been pushed over, long ago; and yet, it remained, stubbornly and forlornly keeping its vigil.

Conor approached it without the timidity of the superstitious Christian farmer, who shrank from such things as fairy-stones and deviltry. To Conor, it was a curiosity, a relic of the past; true enough, though, it had about it an air of the uncanny. There was something foreboding about its blackened and pitted form, an ancient and forgotten sentinel, still standing at watch through the centuries.

But why it had been left there, that gloomy guard of stone, Conor could not tell. Whatever carvings had once adorned its surface, all but one had disappeared with the wear of the ages. The one that remained…

Conor drew closer, peering at the lichen-encrusted thing that was engraved upon its surface. It was a human figure, but one that seemed altogether familiar.

He leaned in, squinting as he struggled to make out its details–then jerked back in horror as he recognized it. It was the thing, the beast from his dream, the devil with the huge, sharp, three-fingered claws. But it was here, too, carved upon the menhir!

How? How had he known what would be depicted on the stone atop the Hill? And why had it been engraved upon the dark and foreboding menhir? Was it an icon of worship? Had some awful tribe in the distant past been devoted to the thing as a god?

“It is a warning.”

Conor whirled about, hand on his dirk, before he recognized the voice as that of an old woman’s. She strode up the slope towards him, following in his path, her footsteps muffled by the dense sward and dew-damp heath. She spoke easily as she walked, not at all short of breath: “It was set there by the First Men, who found this place long, long ago. It was meant as a warning, that men should avoid the Hill, and make their homes elsewhere.”

She halted before him, and smiled knowingly. “Of course, men forget, and the words, the pictograms, are long gone. Not that anyone living would know what they said, anyhow.”

Conor regarded her curiously. She was quite short, yet she stood tall, seeming taller than she really was. Her hair was gray, but her thin brows were still youthfully jet black, and her pitch black eyes were clear and sharp. They stared piercingly into Conor’s, and their sharpness betrayed a keen and clever intellect, and a vast well of knowledge.

“You know much about the Hill, then?”

“I know plenty.” Her keen eyes were mysterious.

“So you’re from here?”

“No, but I’ve lived here many years.”

“And what do they call ya?”

The old woman’s smile turned rather wry, a little bitter. “Various names that aren’t too kind. When they’re being polite, when they need my help, they call me Moira.”

“And why do they call you unkind names?” Conor already had some sense of why.

Moira’s smile faded altogether. “Many reasons. Because they don’t like me, because they don’t like who I am, what I am. Because I have my faith to protect me, and thus I have no need of the damned pact of theirs. Even the priest, bless his young heart; he treats me with kindness and respect, but I know he is jealous and hateful of me…” Her eyes grew cold. “Had I the choice, I would have never permitted what goes on in the village… I was powerless to stop it.”

Conor smiled. “Forgive me, Moira, but it seems you’re doing a lot of talking without saying much of anything.”

Moira’s eyes jerked back up to him. She remained otherwise still; and yet the tiny flitter sent an electric wave through his nerves. “Conor… hold out your hands.”

He twitched. “How did you know–”

“The villagers told me.” She drew closer, her words suddenly impatient, her whole manner eager and nervous. “Please, let me feel your hands.”

There was something in her manner… something familiar, warm, motherly; and yet, it was regal, commanding, as well. He held out both hands, rock steady as she took them, massaged them gently.

A light grew in her eyes. She nodded. “Aye… you’ve Her mark upon ya. You swore an oath to Her, long ago, did you not? You’ve the true faith in your blood, in your soul.”

Conor chuckled nervously. “I’m no Christian, I’m afraid–”

Again, her sharp, icy black eyes met his, and he fell silent. She shook her head. “I speak not of the Pallid Christ. I mean the True Gods.”

He muttered, “Her mark… you mean…”

“The great mother… The Morrígan.”

And he knew, at once, what it was that was so familiar about her. He shook his head. “I’d not thought there were any other of the faithful left… only we sons of Turlogh Dubh.”

Moira smiled. “There are, indeed. We are few, but we remain, those who never surrendered to the tyranny of Peter and Patrick. Even as we attend mass every Sunday, even as we baptize our children in their churches, so too do we still hold the true rituals by moonlight or in hidden caverns, so too do we practice the ancient rite that purifies our children of the taint of the Deceiver’s blood. We swear still to the Tuath Dé, swear by the Dagda and The Morrígan, by Lugh and Brigid and Manannán mac Lir. You are not alone, Conor Dubh.”

It was a strange feeling, a reawakening, a fluttering of a thing long asleep in Conor’s soul. But even as it stirred, the black cynicism of the soldier of fortune reasserted itself. He smiled ruefully, and shook his head. “I’ve never been a religious man.”

Moira’s smile faded. “I was afraid of that. That you’d deny what’s in your blood…”

At last, she released his hands. Only then did Conor realize he had been resting them comfortably in her small, soft, wrinkled own. She took a step back; and suddenly, the regality, the deep and ancient authority, which he had glimpsed in her, fully asserted itself. “Conor Dubh… I ask of you a favor. I do not command it. But I would be sorely wounded, did you refuse.”

It occurred to him that the woman was being oddly imperious for an aged cunning woman, living on the border of a backwater village. And yet, it rested naturally with her. He shrugged. “What’s the favor?”

Moira’s eyes were earnest. “To be brave. To remember your oath to The Morrígan. To fulfill that oath, the oath I know you made to all the True Gods, to have courage, to fight evil, and the forces of the Outer Dark, wherever you meet them.”

He shook his head. “I told you, I’m no believer–”

“But you are sworn to the True Gods–they are in your blood!”

“Moira, I–”

“Please, Conor Dubh!” The pleading in her eyes, in her voice, contrasted sharply with her still regal bearing, in a way that wounded him deeply. Some deep and instinctual part of him wanted to throw himself down at her feet, beg forgiveness for his words, and swear to do whatever she commanded.

Instead, he only nodded stiffly. “What do you ask of me?”

She drew herself back up, and her smile returned. “To prove yourself. When they tell you that you must join in their covenant, I ask you to refuse. Do not fight them–I want no bloodshed, and I wish not for you to show the false courage of shot and steel. Conor… when they come for you, tonight, resist them, with your courage and your faith, alone. Do this, and I swear on the name of the Morrígan, they dare not harm you.”

“What is this covenant?”

Moira snarled with disdain. “Have you not guessed? A blood pact with the She-Devil–Saint Bhavanshi, the priest calls her. A yearly sacrifice–must I make it plain? Must the awful words pass my lips?”

Conor shook his head. His own eyes had grown dark. “I’ll do what you ask.”

“You swear, on The Morrígan?”

He nodded stiffly. “I do.”

Moira took another step back. “Faith, and courage, Conor Dubh.” She turned abruptly, and strode down the hillock. Conor watched her for a time as she ambled back down the Hill. He turned, at last, glanced back at the blackened menhir a moment.

He nodded, and left, walked with an easy, loping gait back to Linton; and he whistled on the way.

#

Peering out the window, Conor set down his beer. He smiled ruefully. They had let him finish his supper… damned polite of them.

Threescore of dark-eyed men, armed with hatchets and long peasant knives, were marching down the village road. At their head was a nervy-looking young priest. Conor turned, glanced back curiously; more sullen-looking men already stood guard at the door.

Conor leaned back and sipped his beer. Faith and courage, Moira had said… He shrugged to himself. Let come what may.

The innkeeper left abruptly, and Conor heard him let in the party, heard muffled, grumbled greetings and the ugly thud of leather boots. The others in the dining room joined the mob without hesitation as the priest marched up to Conor with a strained smile of courtesy. “You are mister Conor O’Brien?”

Conor nodded lazily. “That I am. Conor Dubh O’Brien, at your service.”

“My name is Father Donald. I would like you to accompany us, please.”

Conor sipped his beer and looked about at the others, at the hard and fearful eyes of the peasant mob. He had promised Moira he would spill no blood; but part of him was regretting that oath. Fearful little men were violent and nasty animals. She had said they would not dare harm him–but who was to tell what a pack of frightened, heavily-armed villagers might dare?

The die was cast, in any case. His weapons were in his room; they had him helpless. He finished his beer, and nodded. “Very well.”

Rough hands yanked him from his seat. Conor fought down the urge to wrestle free, crack a jaw or two, and allowed himself to be manhandled out of the inn, down the village road and off into a nearby wood as the young priest led the procession. Now and again Father Donald glanced back, each time looking with chagrin on the rough treatment, but he said nothing.

They halted near the end of the woods trail, beyond which lay a small glade, shadowed and indistinct in the cloudy night. The men parted, and Father Donald approached Conor. Again, he was apologetic, polite. A kind man trapped in a nasty business. “I’m glad you’ve come along willingly, mister O’Brien, and I promise this will be all over quite quickly, and…” He grimaced, and swallowed hard. “Relatively painlessly. However, since you’ve insisted on staying in our village, despite the advice others have given you, we must take steps to ensure your safety. For our own safety, as well, and for our peace of mind, you understand.”

Conor’s smile was fierce as he glared at the priest. “No, as a matter of fact, I don’t understand.”

One of the villagers growled in his ear, “You don’t have to understand, just fuckin’ do it.”

The young priest shot the man a chastising look. The man fell silent, but he looked little cowed. Father Donald wrung his hands nervously about his bible before he continued. “We, of this village, have a… a tradition. A pact which we make, with a certain saint. In return for this pact, she extends us her protection, and we are left in peace.”

Conor’s ugly smile split into an uglier grin. “Just as a bandit promises protection at the point of a sword, eh?”

The villagers glared at him, but they said nothing.

“Please, mister O’Brien, you must understand us. We are simple folk. We have little enough to protect us against worldly dangers. And on top of that, we must contend with…” The priest bit back his words, bit back bad memories, and shook his head. “We are not warriors, or witch-hunters. We have no choice in this matter. And your presence here, your defiance of the authority of our saint, endangers us all. If–when–she wreaks her holy vengeance upon you, she will demand a further… renewal of the pact.”

Conor glanced about at the villagers who pinioned him. Though he felt sorry for the young Father Donald, his sympathy did not extend to the brutish and fearful peasants all around him. Simple folk they were, salt of the earth–and a more vicious pack of beasts, Conor had never known or heard of. Starving wolves in winter were bleating sheep compared to the ruthlessness and savagery of a village mob.

He turned back to the young priest. “What do you ask of me?”

“Only that you join in our covenant, that’s all.”

“And what of this covenant?”

Father Donald hesitated. “As I said, the covenant is a pact with our local saint–”

Conor snarled, “I didn’t ask you to repeat yourself–what is the covenant? What am I binding myself to?!”

Father Donald was silent a moment. “Please… mister O’Brien… will you agree to do this, for our sake? For the sake of the lives of all in this village?”

Conor shook his head. “No.”

“Please, mister O’Brien, we are depending on you to–”

“I said no.” Conor’s voice was a deadly calm. His eyes were iron with his unshakable will.

A short, blunt dagger poked into the bottom of his jaw. The innkeeper leaned in close and snarled in Conor’s face, “You don’t have a choice! You’ll agree to join our covenant, or we’ll make you regret ever coming to this village!”

“Then MAKE ME REGRET IT!” The innkeeper, all the villagers, recoiled at Conor’s explosion. He looked about at them, his eyes livid with Gaelic rage. “Make me regret it! Carve my flesh, break my bones, do what you want–but know this: Conor Dubh O’Brien, of the blood o’ Black Turlogh, never surrenders!”

All around, the villagers’ eyes were filled with hate. But there was fear there as well, a fear that told Conor that, even with him helpless in their arms, they would do nothing. They would not dare.

In the eyes of the priest alone was there no fear. He glared at Conor, and shook his head. “You would sacrifice another’s life on the altar of your pride? You’re a cold-hearted, faithless fool, mister O’Brien.”

Conor smiled. The priest was right. Conor Dubh was a born fool. A fool he had been when he and his best mates had refused to join the rout at Ramilles, when they, a mere score of the Wild Geese, had charged with sword and bayonet into the teeth of Marlborough’s bloodthirsty dragoons, even as the bastards had cut down their fleeing comrades all around. A fool he’d been, indeed, when he’d risked hanging for desertion in order to pursue his blood vengeance against the Duke of Marlborough in the name of his fallen friends. And hanged he would have been, had he not killed three of Marlborough’s best dragoon captains in fair duels.

A fool he was, for those men meant nothing. He cursed himself, still, for all the chances he’d missed to murder the damned Duke himself, and he still swore he’d slay the old Saxon one day.

Conor nodded. “Aye. A fool I am.”

Father Donald’s eyes smoldered. Then he waved to the villagers. “Bring him into the circle. He’ll join our covenant, like it or not.” He snarled at Conor, “Damn you–you won’t be the death of another child!”

The glowering crowd pushed Conor ahead of them as Father Donald walked by his side, muttering a hurried prayer. In the small glade there sat a stone shrine, a crudely carved figure, but Conor knew at once what it depicted. It was draped in clothing meant to imitate Mother Mary, but the gaunt face that stared from under the hood bore no mercy, even in its idealized form. And the hands that clutched at a cross and a small stone bowl were long and clawlike.

The villagers halted abruptly. Father Donald looked up, and his prayer died on his lips. From out of the shadows, there stepped Moira. She stood, adamant and fierce-eyed, between them and the shrine.

Conor knew, then, what he had sensed on the hillock. She was no mere cunning woman. Draped in a long, bright, finely decorated robe, the small woman loomed regal, seemed to tower above the suddenly shrinking villagers. Even Father Donald, clutching at his bible, shrank before her. For she was an arch-druidess. A woman of terrible power.

Conor smiled. He knew now why the villagers had feared so to harm him.

Though her black eyes blazed hot, her voice was icy with command: “No more. It ends here.”

“No!” Father Donald’s voice quavered with forced courage. The priest marched forward to meet her, his bible held defensively before him. “Do not try to stop us, Moira. I will not have another newborn babe’s death on my hands!”

“You already bear one babe’s death, each year. You try, and fail, to console a grieving mother, each year.” She snarled. “Is it so much to ask, to give another lamb of your flock, oh brave shepherd?”

Father Donald shook his head. “That is different. Saint Bhavanshi demands that–”

Moira shouted, “Damn your devil-saint!” The young priest shrank with all the other villagers before her fury. She looked about at the villagers with a baleful hatred, a regal disdain. “And damn you all as well. You need not grovel before her. You need not kill innocent children. I told you how to free yourselves of this blasted pact, and you refused. Do not deceive yourselves. Each year, you feed that devil a suckling babe, because you are faithless cowards!”

Though he was cowed by the witchwoman, there still shone in Father Donald’s eye a certain defiance. He alone looked Moira in the eye. “Call us not faithless, Moira. We fear God, unlike yourself. We love Christ–”

“Ha!” Moira’s bark was utterly mirthless. “The Pallid Christ! You’ve seen what he does for you. It was you, you faithless bastards, who threw away the love and the protection of the Gods, who permitted the return of the demon after she had been caged and banished for so long. You called us heathens, devil-worshipers–but it’s you who’s turned a devil to a saint!”

She cast her blazing black gaze over the people, and to a man, they looked away, even Father Donald.

She nodded. “You come to me, begging help when your animals are sick, when you’ve a weeping sore, aching limbs, when your children shake with fever. But when a beast of the Outer Dark demands the lives of those same children? No–you will not abandon your cold and empty God! You cling to your lie, even as it robs babes from the crib!”

She halted suddenly, her lips quivering as though she wanted to say more. But instead, she puckered her lips, turned about, and neatly and dramatically spat upon the image of Saint Bhavanshi.

Father Donald shot a furtive glare at Moira, as if he wanted to say more as well. He hesitated, then turned and stomped out of the glade. In ones and twos, the defeated villagers turned to follow.

Conor was turning to leave as well when Moira stopped him. The fury in her eyes was gone. In its place was the warm smile, at once motherly and queenly. “You’ve proved yourself, Conor Dubh. You are indeed brave.”

He chuckled mirthlessly. “Foolhardy’s what I am.”

“Well, a little foolhardiness never hurt.” Her smile vanished, and the earnest returned to her eyes. “Conor… will you do one more thing for me?”

He nodded. “What is it you ask?”

#

Conor found himself staring out the window of his inn room, that night, at Linton Hill.

The night was silent, and pitch black; the moon was obscured behind a heavy cloud cover, so that no light, human or otherwise, touched the world. And yet, Conor could see clearly. It was as though the whole of the landscape exuded a strange, lambent indigo glow, like that of the oncoming morning; but where the first light of dawn was a welcome glow, this light was cold. Darker, somehow. Unnatural, and threatening, as though Conor’s eyes were privy to a monstrous anti-light which ever hid in the shadows, only to emerge on the blackest of nights, in the presence of the worst kind of evil.

He shook his head. An eerie sensation. He turned to grab his arms–

The shrill and distant cry froze him in place.

Slowly, something drew him inexorably back round. His eyes were drawn to the summit of the Hill. Again, he felt the creep of the supernatural, the heavy miasma of unwritten ages in the dim prehistory of barbarism, the terror and the struggles against the unmen who were the last survivors of forgotten aeons.

And the terror was not idle that night.

He watched, paralyzed, as a speck gradually formed into a figure rushing with uncanny swiftness down the slope of the hillock. Through the fields it sped, closer and closer as Conor stood paralyzed by his fear. Its bone-skinny legs carried it with an inhuman power, and black, unblinking eyes fixed Conor with a dread hate and hunger.

As it crossed the edge of the fields it grew in his vision with frightening speed. It was taller than any man, like the decrepit corpse of a giant-woman. Its headlong rush carried it through the village in moments.

It disappeared beneath Conor’s window sill.

There was an awful moment of coiled tension.

And then its face burst forth before Conor, as close to the glass as he was, and he saw it in its awful glory. Its corpse-white flesh was pulled tight over its bones, its ragged hair fell back to reveal a tiny, batlike nose and hideously bulging eyes that showed no white, only an abyssal black. Its gaping mouth stretched unnaturally wide, baring gums devoid of teeth, save for four huge fangs like those of enormous vipers.

It screamed its awful, ululating shriek.

And Conor’s paralysis broke. He, too, screamed. He whirled about, seized with an uncontrollable, blind animal panic, and he ran.

Down the stairs he bounded, three at a time, and he charged out the inn door and through the village. All the time, the screaming sounded, just behind him, over his shoulder, driving his fear as a whip.

Like a panicked rabbit he fled, heedless of his direction. He ran past dark and silent houses, he ran through fallow fields, he pushed silently past the weeds that caught at his clothes, dragged at his flesh. The only sounds were his own pounding heart and the piercing shriek that dogged him, that drew ever closer.

He crossed the edge of the fields, and charged through the heath. He ran and he ran, and even as he felt his heart would burst, his terror drove him to run faster.

He ran up the side of the hill. He was being driven, a terrified animal. Driven, to that summit. Driven, there to die, Driven, by his own fear–

And then, an emotion even more powerful than the all-consuming terror stopped him cold. Shame.

Was this Conor Dubh? The same who’d received the charge of English and Dutch dragoons time and again, without balking? Was this the same who’d killed two grown men in duels before he reached sixteen?

Was this the same who, on his eighteenth birthday, had made a blood oath to The Morrígan Herself, never to surrender, to fight ever against the enemies of the Tuath Dé?

No, damn it! This was the same man–and he would run from nothing!

He whirled about, and as he did, the beast slid to a stop not ten yards away. The only sound was Conor’s pounding heart. The thing’s dread shriek was silenced. It was stunned. The hate and the hunger in its eyes was shadowed by doubt–and fear.

It felt it, as Conor did. The Morrígan was at his side. She, and Mannanán mac Lir, and Lugh of the Long Hand; they were all there, the shadows of the Gods, as mere whispers, reflections of what they once had been. Yet even that whisper, that breath of force, could blow aside all evil.

Conor reached to his side. His weapons were suddenly there. Given back to him by The Morrígan. He drew and cocked his two pistols, aimed both barrels at the beast.

The thing shrieked again. And this time, Conor answered, with his own bloodcurdling howl, the battle cry of the O’Briens: “Lámh-láidir abú!”

The thing charged. Conor fired off both pistols, shot her in the chest with both barrels. The she-devil’s shriek grew agonized, but she did not so much as slow down.

Conor threw both pistols away and ripped free his claybeg and dirk. The thing leaped. Conor’s claybeg whipped through the air, and the steel bisected its narrow torso. The thing’s shriek took on an awful quality as black blood and grotesque and alien offal spilled from the stump.

Yet the thing lived!

The top half landed on Conor and its claws bit home, sank deep into his flesh. He howled in pain and struggled to push the thing off, but it only bit down tighter. With its inhuman strength it drew its jaws closer, pulled its slathering fangs inexorably towards Conor’s throat. Slain as it was, it meant to take him with it.

Bracing against the thing with his swordarm, Conor freed his left hand and plunged his dirk again and again into the thing’s chest, butchered the beast into a bloody travesty. Still it drew closer, still its fangs sought his neck. Conor stabbed and stabbed as the lances of pain tore through his back, as the blood soaked his clothes, as the huge claws shredded his flesh. He stabbed, and he howled in defiance: “Lugh! An Dagda! Morrígan! Their curses upon the Old Night! To Oblivion with you, ya fiend! Die! DIE!”

The thing’s eyes dimmed–

And Conor sat bolt upright, his arms flailing. He threw his sheets off in his blind struggle, before he realized he was still in his bed.

He sat, panting, for a moment, before he grabbed at his back and shoulders. Nothing. No blood, not even a scratch. The searing pain from the dream lingered, but he could find no sign of a struggle on his body. Save, of course, the sweat that drenched his bed.

He chuckled a moment, then broke into a wild, exuberant laughter that filled the whole inn.

He was gasping for breath when he heard the pounding at his door. It was the innkeeper’s daughter again. Her voice was frantic. “Sir! Mister O’Brien! Are you all right?!”

Conor took a deep breath. “I’m all right, lass! Just a bad dream’s all. Say, could you go downstairs and fetch me a beer? I’ve a powerful thirst, and not for water.”

As the mousy little girl ran down to the first floor, Conor grabbed his sheets and threw them back over himself. He lay back, and relaxed, smiling.

After a moment, he frowned.

There was a great commotion downstairs. Men talking, then shouting. All at once, many boots marched up the stairs, halted before his door.

A fist banged at the door. The innkeeper called to him: “Mister O’Brien, are you decent?”

Conor frowned. “I am.”

His frowned deepened as the innkeeper unlocked the door and let himself in. He was followed by what must have been half the men in the village. Conor stared about in surprise. Only a few men had been downstairs when he’d taken his dinner and his nightcap. Where in hell had they all come from?

He chuckled. “Lass, I asked you to bring me a beer, not the whole damn village.”

There were looks of astoundment, of disbelief, on the faces of all the villagers. And, on several of them, disappointment. Old man Keith was shaking his head and muttering, “’S not possible… not possible…”

Of course. Conor laughed. They had all come here for a death watch. They’d all expected to hear his last scream, and to come up afterwards to find him lying stone dead.

He shook his head. “I hate to disappoint you gentlemen.”

The innkeeper stepped forward with trepidation. “Sir… mister O’Brien… did you see her in your sleep? Did you see the She-Devil?”

“I did. And I slew her.” Conor shrugged and grinned at them amiably. “Simple as that.”

Old Keith shook his head furiously. “It’s not possible! The She-Devil slays all she visits!”

“Slays all she visits?! You damned fool–damned cowards, all o’ ya, her power was nothing but a dream! See here!” Conor pulled his shirt off. “See–in my dream, she clawed my back to ribbons. And yet, do you see any marks upon my shoulders or back? Any of ya?”

There was a silence in the room. Ashamed eyes drifted from Conor’s shoulders down to the floor. The innkeeper muttered, “There’s not a mark on you, mister O’Brien.”

“Indeed there’s not! She killed you with a dream. Killed you with fear. By the Devil, if but one of ya’d had courage, then–”

A bloodcurdling shriek sent Conor hurtling out of his bed as the villagers froze in fear. He was on his feet, in a fighting stance, before he realized it was the innkeeper’s daughter who had screamed.

Her eyes were glued to Conor’s sword and dirk. And now, everyone’s eyes followed hers, and the eyes of the villagers went wide with shock and horror at what they saw.

Blood dripped from both scabbards. Blood, hideously black and thick; blood, that could had spilled from no human vein.

Conor slid both blades from their scabbards, and examined them, brooding. He nodded. “More than a dream, then. Well… no matter.” He turned on the villagers, and they shrank back from the black Celtic rage, the born-again fanatic’s fury, that twisted his face.

Conor growled, “Aye… she’s dead. I killed her. No denying it, have a look for yourselves.” He took a step, two steps, towards the villagers, and they crowded back against the wall, recoiled from his fury. “If you’d but listened to Moira, if you’d but given yourselves to the true Gods, you might have stood a chance. With their strength, you just might have defeated her.”

Though he trembled still with fear, the innkeeper met Conor’s baleful gaze with a glare of his own. “And you’d have us deny God, turn to Moira’s pagan deviltry? You’d have us turn our backs on sweet Jesu?” His voice shuddered with anger. “You’d have us sell our souls to devils?!”

A snarling smirk twisted Conor’s scowl. “Aye… you’d still cling to Christ, wouldn’t you, you stubborn bastards?”

More angry glares joined the innkeeper. Frightened as they were, the villagers remained proud, and stubbornly pious. Conor nodded. “Well… no matter. Do what you want now. Your devil’s banished.” He bared his teeth in a vicious snarl. “And you need not feed her any more CHILDREN!”

A moment, the villagers strained against their own fear. A moment, they were frightened, snarling wolves at bay, facing down a roaring lion.

But the moment passed. No violence exploded from the strain.

Wearily, Conor sat on the edge of his bed. One by one, the people left his room, muttering darkly amongst themselves of the black witchcraft and deviltry and heathenry they’d witnessed that night.

Last to leave was the innkeeper’s little daughter. A moment she tarried, pretending to tidy up the room. Her father shot her a wary glare, but she shied from his gaze until she and Conor were alone.

She glanced up at him, and smiled. Tremulously, she whispered, “Thank you, sir.”

Wearily, Conor smiled back. She hurried out of the room, closed the door gently.

Conor brooded a moment after they left. He felt, just then, as a knight errant, a hero of the Old Gods, of the True Gods; and Moira, his queen, in whose name he slew the ancient forces of wickedness who even now were crawling forth to bring upon the earth a new dark age.

Aye… what a life that would be. Traveling from town to town, country to country, a lone defender of the light. And his only pay, the thanks of a timid girl.

Not exactly a good way of filling one’s belly.

Conor smiled ruefully. If he was going to commit to this life, he would definitely have to get paid in cash.

________________________________________

Rev. Joe Kelly is a connoisseur of cheap beer, good metal, and quality fantasy. He has been previously published in Cirsova. He can be occasionally contacted on twitter at @reverendjoefake when he bothers to check it.

Karolína Wellartová is a Czech artist, painter creating images predominantly with the wildlife themes, nature studies and the literary characters. She’s mostly inspired by the curious shapes and a materials from the nature, but the main source still comes from literature.

From a young age she tried to express herself and her observations on paper. Painting and drawing were always the most important thing for her and visiting the local art school helped her understand the new techniques and the science of the colour mediums. She’s the award winning artist for “Best Book Cover in 2015” in Czechia.

Her work has been published in American magazines such as Spirituality Health Magazine, International Wolf, Metaphorosis, Orion, and Heroic Fantasy Quarterly. Check out more of her work at her website.