THE GREAT HUNT

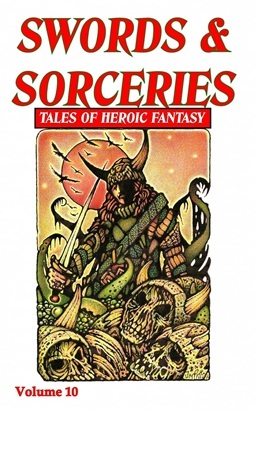

THE GREAT HUNT, by Francesco Meriano, art by Miguel Santos

1. A Field in England

We were traveling across Yorkshire, on a Midsummer’s Eve like many that had graced the thirteen centuries since the birth of our Lord. I led our old donkey Bess across the worn gravel path, spurring her gently through the warmth of the afternoon. Crickets chirped in the meadows, nestling in the long, pale grass swaying at the breeze: their murmuring blending with the crunching of hooves on pebbles and the ever-present drone of insects.

The day was indeed pleasant enough I began to doze, or I would have, had the Magister not been with me. “Pay you for napping while on duty, do I?” He chided, his brittle voice breaking the lull. He sat in the back, as he’d always done ever since I had the dubious pleasure of serving him: bent, aged and wrinkled, his gnarled frame huddled in a filthy grey robe and a heap of mouse furs despite the heat. A most unpleasant man he was, hovering there in the back like a stunted bird of prey, and in all the years I’ve spent with him I never found a living being who could abide his company for more than a few days. It was the third year of my service.

“See, you do not actually pay me, lord – ”

He waved the objection aside. His right hand, skeletal and blotched with age, was wrapped around a wooden staff which I’d found he could still use with unusual vigour, and which gave the old man a major asset in any verbal confrontation. Unable to withstand the subtlety of his argument, I bowed my head in surrender like Bess the donkey did when reined in, and tried to keep my tired eyes open. Why, I wondered for the thousandth time, was I there? Thoughts of ancient lore and lost Byzantine scrolls from the far side of the Oikumenes surfaced: but then again, I would have exchanged them in a heartbeat for the safety of the monastery and its renowned apple pies. Feeling dejected, I wrapped my novice robe tighter around me, for the wind had risen: and the air, with yet another change of humour of this old voluble English land, suddenly felt sharp and chilly.

The Magister’s hand clawed at my shoulder, his untrimmed nails raking at my skin. “Stay silent!” He hissed before I could speak: and there was no questioning him. After a moment, I dared raise my head to see what had alarmed the old man.

It is a widely shared notion, that the strange and bizarre secrets of this world manifest themselves only at night: and that creatures such as those the Magister and I hunted for a living always lurk under the cover of darkness. The day belongs to man and his routine life, from the farmer scything ripe grain to the king who commands justice and the spears; and there is no place for haunting fires or Sabbaths in the midday light. This self-same notion was one of the first the Magister saw fit to disabuse me of.

There was no dancing fire or witch in that Yorkshire afternoon as I gazed around. The sky sparkled blue, beautiful to make the heart ache: the crickets sang their song. Yet the low hills seemed now paler; the lilacs brilliant with a brighter purple tinge; and I wondered what lay beyond the hedgerow snaking at our right, with the wild rosebuds blossoming in crimson amongst crumbling white-washed stones.

Then I looked in the direction of the Magister’s pointing finger. At some two hundred paces from the cart, where the gravel path rose to wind itself across a domed grassy hill, stood a black dog. It was a huge beast, its hind legs thicker than my arm, haunches rippling with strength under glistening black fur. As I looked, the beast turned the shaggy head to me, and even from that distance I could see his eyes were of a brilliant red.

The crickets’ chanting had risen. Now, mingled with the rustling of tall grass against the rising wind, it seemed to shift and clash and clamour in my ears. For a moment I thought I was hearing the chaotic trumping of fanfares, the piping of wild flutes, and the rumbling of leather drums; overcome, I closed my eyes.

When I reopened them, the dog was gone. The wind had subdued, and the chant of insects faded once again in a susurrus. I turned to the Magister, blinking: but his gaunt ancient face was creased in worry.

“We must move, apprentice”, he said. “The Hunt has come.”

2. A Lord and his Sorrows

The castle had seen better days. Its stone walls were streaked green with moss and lichen, the low circuit of the ramparts crumbling down as mortar turned into dust with time and neglect. Once it must have dominated the valley, rising from its sheltered perch on the high hill to loom over the serfs and peasants labouring in the fields, which now lay untended and overgrown with vegetation. On the square barbican a ragged banner hung limp.

At the Magister’s bidding, I drove the cart up the low incline towards the gates. Here and there I could see the remains of a stockade, lone brown stakes which made me think of rotten teeth. Beyond, a wooden causeway bridged a shallow moat already half-filled with mud from the early summer rains.

Two guards in leather jackets and half-helmets stopped us at the gates. One of them glared at me, but when he saw the Magister, he paled and hurriedly bowed his head, gesturing us in as his companion shouted for the gate to open. The old man grinned in satisfaction, baring yellowed gums.

We left Bess to the dubious care of the sentinels. I tried to help the Magister out of the cart, but he swatted my hand away – as I knew he would – and steadied himself on his staff. Despite the thin sun rays filtering through cracks in the gallery, it was cool and dark: the Magister’s staff punctuated each step with the hollow sound of wood striking against stone. Thus, we were admitted, without further impediments of protocol, before the lord we’d come to see.

My first thought was, he looked exactly like the fortress he ruled – dejected, and squalid. He sprawled on a high-backed chair, a cup of wine sloshing in his hand: the shifting light of flaming torches gave a yellowish tinge to his fleshy visage. Flushed jowls and drooping eyelids betrayed the excessive use of unwatered wine, a vicious practice in which the Magister too loved to indulge, despite condemning everyone else who similarly lacked in self-control as a useless piece of drunken dung. Even though he could have matched the baron with the cup, I should also say that the Magister had the uncanny ability to keep his wits about where an Everyman would long have abandoned the path of sanity: I’ve seen him inhaling the poisons of the eastern Hashishins while reciting backwards the infernal hierarchy of daemons as theorized by Psaellus, just to show that he could. But I digress; and he could be an insufferable old man anyways.

The baron rose ponderously to his feet, spattering wine over a thick grey moustache. He swayed, grabbed at an armrest, and stood. “Who in the seven Hells…” He squinted, finally making out our figures in the gloom. Piggish eyes squinted in suspicion and I felt his hostility as his gaze rested briefly on me – then it widened as it took the old man in. Fear, mistrust and reverence struggled on his face for a moment; then he sank down again. “Magus. We expected you for the harvest.”

A poke of the cane instructed me to slide away. The Magister hobbled forward, ragged robes swishing against the dusty stone floor. “Such cases do not wait for the convenience of lords,” he rasped. “Even now it might be late, for I’ve seen the Black Dog on your doorstep. And the Hunt is coming here.”

Murmurs swelled at the corners, where the baron’s courtly retinue huddled in the shadows. I glimpsed ragged cloaks and hastily sewn brocade. Like their lord’s, the garments were stained with wine or grease, some coated with grey dust; pale hands rose to draw the cross through the dank air.

No words could have had a greater effect on the baron. He seemed to age ten years more in a heartbeat – the portly man, on the brink of passing from stout strength into corpulent decay, shrank to an ancient under the dancing torches. He pursed his lips, bone-white knuckles gripping the carved armrests. “This is not true, it cannot – you lie, wizard.”

More crossings flew at that. To insult a wandering magus is never a wise thing; for a moment, the old man’s eyes flashed. “I am not called a liar lightly, lord Gorey. Deny it if you wish, but the hunt has finally begun, after all these years. And the game is none other than you.”

With growing unease, I saw the baron’s guards fidgeting with their weapons. When are the heralds of doom ever welcome to a warm hearth, even though their warnings be truthful? The baron ran a hand through his receding hair. Squinting in the semi-darkness, his pudgy face regained some colour. Beads of sweat ran on his forehead.

“You yourself called for us last month, lord” I ventured in a whisper.

The baron turned to me. Perhaps he found in my tonsured head and shaven chin an easier target for his disquiet to focus, and he slammed a fist against his thigh. “I called for truthful counsel and protection, not the nagging of a priest! The Hunt… Pah. I’m not a man to lose the wits when he’s threatened, to be cheated of my gold by some tale-spinner.” A nervous grin spread on his face. “No, ’tis a curse. An envious neighbour, a woman with a grudge, and a country witch that I haven’t burned yet. Counter it, Magus, and you shall be rewarded handsomely. But try and cheat me, and by all means I’ll have some dry kindle stacked in my courtyard just for you.”

At this point I was all but quavering. Insulting the Magister to his wrinkled, damnable old face – even now that he’s long dead I shiver as I turn these thoughts into ink, as if his gnarled form could again appear from the shadows to curse me in the name of Jesus, the Virgin and Duke Arioch. I remembered wondering why this baron, afflicted by a menace from the other world he could not hope to evade alone, would turn down his only possibility of salvation. But then again, I was young, and unfamiliar with the flaws of a mind. The baron was sick with fear: terror and danger made him lash out indiscriminately. Or maybe he was just obtuse, and took comfort in haggling like a fishwife with what low cunning he possessed. But to all effects, he was cornered animal, and deep down I dare say he did know the truth of it.

Yet the explosion did not come. To my surprise, the Magister bowed his head. “Indeed, you must be right, my lord – but I do not sell my services for trivial matters such as curses or evil-eyes. With your leave…”

He turned, gesturing me to follow with a careless wave. “Come on, apprentice. We’ve wasted our time.”

“No!” The baron’s voice boomed behind us. “I do not give you leave, wizard – not till you dispel the curse.

Guards -”

Everything happened very quickly then. I spun back to the baron, mouth open in protest as he rose and staggered towards me with his fist still wrapped around the wine cup. A cry of horror resounded from the court. Two armed sentinels reached for the Magister, but one of them lost courage and fell back. The other raised his spear, pointed it against the old man’s scrawny chest.

I blinked, and the Magister stood before the kneeling guard, bony fingers casually twirling the wooden cane through the air. The sentinel was clutching his right hand, his spear tumbling to the floor a few paces away.

In the sudden, shocked stillness, the clattering of steel on stone resounded like a war horn.

“Touch me”, the Magister said, “and you shall never see the light of day again. The bats of Hell will gouge out your eyes to leave you groping blind in falling darkness. Your entrails will turn into snakes and squirm their way out through your soft flesh. Touch me, and you will rot from inside, your liver turning black and shrivelled like the piece of dung you are.” His voice rang loud and clear across the stone vault. No trace was left of the wheezing and rasping I had known.

“Your piss will burn like fire. Your skin will burst and split in sores. And when you are crawling on fours and begging for death, I shall feed you to the White Worm which dwells under the Goth’s mound.” His rheumy eyes shone like obsidian beads. The ragged grey robes billowed of a sudden around his ancient body – but under the cold draught blowing in the hall, I felt sweat coursing on my forehead.

Without sparing a further glance at the man, the Magister whirled back towards the baron. Such had been the effect of his words, that for a moment I convinced myself the old man was growing taller: and wasn’t his shadow more imposing, stretching now the length of the stone wall?

The baron cringed before the pointed cane, and through my disquiet I experienced a surge of satisfaction. The man’s eyes were wide, his mouth quivering. Twice he visibly tried to pull himself together; twice he sank back into his chair, smacking his lips. The Magister stood silent for a long moment, narrow eyes glinting darkly in the torchlight; then the wind abated, a log in the hearth crackled, and he sighed. When he looked again at his terrified employer, he was again a hump-backed miser leaning on a staff and dressed in nondescript rags.

“Whatever ails you, lord, I should be able to cure” the Magister said in a mild tone. “As long as you provide payment, and due respect and manners towards me and my apprentice.” He shrugged as he pointed at my person. “Please escort us to our chambers, Gorey. I’d like to know how your situation came to be, from your own lips and in private. Unless, of course, you think another lying wizard wandering this waste might be more of use.

What say you?”

The baron gracefully agreed.

3. The Baron’s Tale

The lord’s chambers were no better than the rest of the castle, filled with the pungent odour of dampness and stale air. Baron Gorey fell into a cushioned chair, head bowed down. Mice scurried at the Magister’s feet as he nestled into a similar seat on the far end of the room. I looked around. A painting on the main wall seemed to be the only furniture beside the musty bed and a wine cupboard: it portrayed a tall knight in battle armour, blonde locks falling on cloaked shoulders.

The baron followed my gaze. “A long time ago,” he muttered, and I didn’t ask. Dusk was falling, the last glinting of the sun flashing through the open window. The Magister had uncorked a bottle from the cupboard and was now guardedly sniffing its content. “Poor vintage”, he spat, and took a long draught.

I am sure Lord Gorey could have used a sip, too. As the Magister drank in silence, letting rivulets of liquid spatter down his robes, the noble tried to begin his tale. He licked his lips. “It was ten years ago, I think. I was lord of Berkshire at the time. The king…”

An empty bottle shattered on the floor. The baron’s voice petered out. Without sparing him a glance, the Magister yawned. “Another bottle, brother Daervel, if you please.”

I hurried to the cupboard. Now the fear on Lord Gorey’s heavy face jostled with repressed rage. He made to utter something, a protest or a blasphemy, or both. Taking a deep breath, he finally raised his head and looked us eye to eye.

“It began with the goddamned wood,” he said.

“It began with the goddamned wood.

I’d gotten it with a land grant from the king, back when I was serving as a knight for the earl of Berkshire. Not that I would have imagined it possible back then, since I was just a second son, newly invested with knighthood and penniless as a wandering minstrel. But just like a minstrel I could sing a bawdy thing or two, and the Earl took me in his good graces. I used to accompany him for official occasions, but most of all I was his best trusted companion for a good hunt – a passion we both shared. He went out for deer mostly, but I always was more daring. There is nothing sweeter in life than the blood pumping in your veins as you spit a charging boar on your spearpoint, to finish him as he trashes on the ground. And how they all cheered me afterwards! The fellow nobles, the knights and hunters and the squires, down to the lowest serf. And when we returned to the manor, I was always sure to get a different sort of cheer from the washerwomen. Sometimes from the earl’s wife too – pretty little thing she was, but bold in bed as any I’ve ever known.”

We sat and listened in silence. As he spoke, delving deep into remembrances of happier times, the baron’s flabby visage gradually relaxed, the look of helpless anger fading away to one of tranquil satisfaction. I was expecting the Magister to interrupt him with a tart comment at any moment now; yet when I risked a glance at him, I saw him listening attentively. His shrivelled face was stern, lips set in a tight line; only his dark eyes, strange enough, glistened with what I thought could have been contempt. Or conjunctivitis.

“Those were good times,” the baron went on. “And the best ones were yet to come. I knew I was the best of the lot at court – un-weaned puppies playing at mock war, catamites and painted trollops, all of them. But I came from a disgraced family, had known hardships such as those the earl could never have conceived. I’d spent years bowing to presumptuous little shits, saying “yes lord”, and “nay, lord”, and for all that time I’d waited for just the one occasion I needed.

It finally came from the earl himself. He was the worst of them, you see. Old, patronizing and obtuse. Always believed himself better than he was, because his lickspittles kept telling him just that. And thus, the day came when he thought it a good idea to show his warrior prowess and face a cornered wild boar alone.

Can you imagine such a folly? A pampered old man, nearly sixty, against the most vicious looking beast I’ve ever seen. It killed the earl’s horse at the first charge, sent the man tumbling against a tree, saddle, lance and everything. He squealed like a baby when the boar came back for him.”

Gorey grinned. “It was then I intervened. The boar must’ve been crazed – the earl was the only thing it could see. I ran up to its side and buried my own spear deep into it. The moment I took out the hunting knife to finish it, I knew I’d finally made it.

I don’t know if fright or age had loosened something in the man’s head, but from that moment on the earl only had eyes for me. He petitioned the king for a title, covered me in gifts, and granted me the fief of Berkshire Forest as my own. You see, Magus?” The baron’s small eyes glinted fiercely. “From a nothing to a lord. And then on to more – I visited the King’s court, made powerful friends. And with them came more land, and serfs, and men-at-arms. I gambled and plotted and suffered for all this – and now, someone seeks to take it all from me!”

The baron’s last words almost choked in his throat. Indignation had flushed his cheeks with new colour; he sweated copiously. For the first time, I truly gave attention to our host. It was hard to reconcile the aging, wheezing figure sprawled before us with the fair knight gracing the portrait. Could the years wreck such outrage on a man, dissolute though he was? Summoning my courage, I spoke to him for the second time since we’d entered the castle.

“What happened then, lord?”

To my surprise, this time Lord Gorey looked to me almost in sympathy – and I felt soiled by that impression. Shrugging his wide shoulders, the baron gave a grin. “And then, priest, I fell in love.”

Outside, the sky had taken a dull purple sheen, like a fresh livid. The chamber was darkening, and the Magister on his chair was but a gnarled silhouette in a grey cloak. There was no brazier in the room; and I shivered as the shadows grew and lengthened around the baron’s massive figure.

“She was little more than a peasant – the wife of one of my newest landholders. He was a dull man, straw in place of brains, and the folk in Berkshire used to whisper behind his back of her infidelity. She snuck out of their house at every full moon, they said, and went deep into the woods to seek her lover. Names were made, and yet my tenant would not send her away – wouldn’t even beat sense into her.” Gorey curled his lip in disapproval. “I would not have delved into the busy little affairs of the smallfolk. But she was a pretty thing, I admit, and the whole story had my curiosity piqued. So, one night I took two of my most trusted men, donned a wide traveling cloak, and rode to their farm at the outskirts of the forest.”

Huddled in his chair, the Magister bowed his head and sighed. I thought he must have known what would come after; perhaps, I have then mused, he’d known since seeing the black dog on the hill that morning. His tired nod was lost in the deepening gloom.

“My hunting days had taught me one thing or two about following a track. She left the house, just as I’d been warned she would, and we followed, unheard and unseen. Soon she strayed from the main path, and into Berkshire Forest.

It wasn’t easy, I tell you. She moved lite as a deer, and more than once I thought we’d lost her for good. There were rough tracks in the forest, but she avoided them when she could, skulking through branches and fallen trunks. My men tried to convince me to turn back. But now I wanted to see – what kind of woman would stalk a wood in the dead of night just for an hour’s pleasure? Soon afterwards we saw a clearing. I should’ve gone then, should’ve forgotten that unholy witch. But curiosity spurred me on.”

Curiosity and lust, I thought, but held my tongue. And was it not his right as a lord to follow his servant through a wood, and there to bed her if he wished? Yet now the baron faltered. Suddenly he sought the Magister’s eye: but the old man’s gaze was unforgiving. Lord Gorey took a shuddering breath, and went on.

“There was an old altar there, a crumbling slab of stone: something the Romans left behind, perhaps, or something older yet. And around it there were squirrels, and wild rabbits, and flocks of birds crowding up on the branches – and a stag, a magnificent beast, antlers sharp as blades. Never had I seen so much game at all. I – I think they all waited for her. She walked to the stone without a sound, with the beasts circling all round her – not one of them showing a sign of nervousness or fear. I could hear more of them rustling beyond the clearing, unseen under the branches blocking out the moonlight. The woman knelt before the stone, and the deer raised his head and bellowed.

To this day I cannot recall precisely what followed afterwards. I remember all the birds taking flight at once, swirling out into the sky like a living gust of wind – the rabbits scurrying all around the clearing and beyond, slipping past my ankles, and the deer standing still in the mist of the exodus, the damned beast. It was then the woman began to sing, a chant the words of which I could not even fathom. Then it turned into a high keening sound, a screeching like the raking of a sword against a whetstone. The birds whirled and spun around her, and the stag, the finest prize a hunter could desire, stood there and watched it all…

I burst out of the woods. I’d seen enough to understand such a woman could have no lover beside the Devil himself – she was a witch, bowing to the horned gods of old before that accursed altar.

I went in with a shout. The birds scattered as I drew my sword. The woman turned to me, screaming, and I saw she had unlaced her dress, and her breasts dangled free and bleeding from the clawing of the birds. One of my men had brought a crossbow. His dart took the stag in the side, sent it stumbling away in fright as the witch shouted and cursed at us. She promised us revenge, and eternal torment. Said our fortunes would crumble like dust against a storm for our sacrilege; that we would hear the wood itself coming to punish our sins. She cursed me and my line down to my grand-children, and it was then I struck her.”

I shivered. Despite the cold, the baron was still drenched in sweat; his breathing came in ragged gasps.

“I took her there and then, on the grass beside the altar. It – it was no more than she deserved. God knows how long she’d been communing with the Devil in that glade. And she’d cursed me already, tempting me with her beauty. I punished her…”

“You violated her.” The Magister’s voice cut sharp into the tale. I crossed myself, my gesture slow and in full sight of the baron; Gorey gritted his teeth. “She’d wanted it all along,” he snarled. “Couldn’t let her defile my lands any longer. And she did tempt me…” His voice faded, and the baron hung down his head.

“Did you bring her back to the village, lord?” I asked. The Magister shook his head, a bitter smile stretched on thin lips; the baron hesitated. His eyes fell on the wine cupboard.

“Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live,” he quoted finally.

The silence stretched on. I thought of that glade in Berkshire Forest where the fallen lord had buried a girl and his own shame into the mossy soil. Was there something true in that tale, I wondered? Or was he seeking to avoid judgment by dressing up a squalid act in the garments of the unnatural? Still that bitter, knowing grin hovered on the Magister’s features; Gorey could not look him in the eye.

“The deaths began a month later”, the baron said.

“Otto was the first. He was one of my companions of that night, the one who shot the stag. One night at a banquet he went out of the hall to make water and did not return. We figured he’d gone down to the village looking for a girl. I found him two days later, as I hunted – he’d been nailed to a large trunk at the outskirts of the forest. His tongue had been torn out, and the ravens had eaten away his eyes already. A black-shafted crossbow quarrel stuck from his mouth into the trunk.

I had the village searched for arms; the folk threatened with death. No one would speak of what had befallen Otto that night. Ah, someone knew, I am sure. Yet it was as if the murderer had ripped out their own tongues as well. Traitors and pagans, all of them. I discovered that the husband of that witch had disappeared from his house a month earlier, and no-one had seen him since.

A week later, Hugh died. The other man who’d gone into the woods with me. He hung from the old birch under the castle walls, rocking against the wind – eyeless, tongue-less, and with a pair of antlers wedged into his cranium.

There were executions then. The smallfolk would not speak. The first two men I beheaded: then, when the kennel master was found hung as well, I began using rope. Every one of those peasants squirming up a branch could have been the murderer, I would think, and would sleep better for a while. And then a fortnight later another of my hunters would die, with a snapped neck or a slit throat. Their fates not as bloody as Hugh’s or Otto’s – but enough for me to lock my doors, for the women to wail, and for the fear to spread.

The killings would cease for months at times – time enough for me to dare and take a breath, and hope for some relief. I would think the bastard must’ve been amongst the latest executed from the nearby farms and villages and steadings, and my court would repopulate with new hunters and squires sent by the fellow lords. And when the blood again began to flow, so the horror resurfaced as fresh as ever.

People began to whisper there was a devil hiding in the woods. Some claimed to have seen him, described a tall stranger cloaked in furs with the horned head of a stag and a bow in his hand. They said I’d brought the punishment upon myself from my impiety, that I had killed a holy woman. God knows how they knew it had been me. And after a while I found that each new death gave those wretches courage. They’d bow to me before, but now they stared in silence when I rode down to the villages. Some even slung stones against my retinue. I…”

“It was Herne”, the Magister interrupted. ” Herne the Hunter. In the woods you defiled His sanctuary and His priestess, and now He seeks revenge.”

Herne. The name hung in the air, spoken out loud at last in the dark chamber. Memories surfaced of the winter nights in the monastery, when I and the other novices would gather in secret in one of our cells and tell stories of daemons, and of lost souls howling in the wind. Someone would point to the forest, its treetops looming black in the night, and cross himself as he talked of Him. Some said He was a spirit of the woods; others, that he was the spawn of Satan. A few, like the Magister, talked of ancient Roman deities, and of earth gods older yet, displaced by the coming of the Cross and now confined to the darkest corners of the world.

I did not know the truth. Indeed, I once heard the great theologian Albertus Magnus say there are as many truths as grains of sand in a vast desert. I found that notion insupportable at the time, having scant patience for the interminable dissertations of my superiors over the sex of angels or the ascendancy of Abraham. The truth of God could not be anything but absolute, and so must be its earthly proof. I wanted to witness a miracle, the irrefutable manifestation of a Power, either holy or infernal: because of this I’d left the warm confines of my cell in the Benedictine abbey, skulking away like a thief in the night and in defiance of our Lord’s warning about practitioners of magics.

Thou shalt not suffer – and yet.

The long years of my life have since eroded the foundations of that certitude, and my esteem for Albertus has grown. My adventures have left me with but a handful of sand, already trickling through my fingers, and with far more questions than answers. We are lone wanderers in the desert of creation, yearning for God to show us the land beyond.

“Was the husband never found?” The Magister had cocked his head on one side, eyeing the cupboard. I found the question strange, and the baron shrugged it away in frustration.

“Does it matter? No, they never found him, or his body. They were too busy slinging stones, or hiding hoarded gold, or lamenting a poor harvest when I required my due. I hired trackers, mercenaries, sell-swords and assassins. Every one of them returned empty handed, or did not return at all. I moved from one castle to another, and yet the deaths followed me like a shadow, whenever I went. Courtiers began to drift away for good, my gold dwindled. Eventually, when I rode to torch the Berkshire woods and end it once and for all, I found an armed detachment with royal insignia waiting for me. The king, I was told, had revoked my title over the county.”

Gorey’s hands curled into fists. “The murdering bastard took it all from me. I spent ten years looking over my shoulder, seeing him in every shadow and behind every corner, while my enemies at court shamed me, plotted, and stole my lands. Ten years in which I had to fill my court with drunken sots and whores. Ten years dreading the message which would report another killing of a mercenary or a soldier. Ten years waiting for the next slit throat, expecting it to be mine. And he shall come to that, if I leave him the possibility, aye – but I am not defeated yet.

I still have gold enough. Destroy him, Magus, and I shall make you wealthy enough for you and your apprentice to cease traveling from one shack to another. I shall rise again in court, and you shall not be forgotten.” His sudden energy seemed to fade again; he bit his lower lip. Then, after a moment, he asked the last question. “The Hunter, if it’s really him.

Can it be destroyed?”

The Magister stood up, both hands clasped around his cane. “The Hunter is playing with you, Gorey, like a cat with a trapped mouse. He is a creature of strength and cunning, one you could not hope to match alone.” His grin was veiled by shadow. “But everything has a weak point. I believe I can put an end to the matter – if we strike fast enough, and hard enough. And then we’ll have to talk about that reward of mine in detail.”

For the first time, I saw hope flashing into Gorey’s small eyes. He leaned towards the Magister, desperate and belligerent in equal measure. “What would you have me do?”

“Gather your hounds tomorrow morning.”

Gorey shook his head. “I’ve tried hunting him down before, and never even caught a whiff of him. What makes you think it will be any different this time?”

“This time you have my magic, baron. And the Black Dog has already come. Set out tomorrow, and I guarantee you shall find what you are looking for.” The Magister draped his ragged cloak around his shoulders. “And now I tire of foolish questions from a foolish lord. Be ready to move on the morrow, Gorey.

Herne comes, and there is game to be hunted.”

4. The Great Hunt

We departed at daybreak.

The column winded through the woods like a long snake of steel and leather. All around me and the Magister I could smell the acrid scent of sweat under the pale rising sun, see the glinting of honed swords and spears through the green canopy of trees. Sunlight dappled on the thick branches and the rich green of foliage. Horses trudged slowly forward, their hooves squelching into soft, dark humus.

Even to my scant experience in matters martial, the baron’s men looked like raiders more than hunters, their bearded faces hidden under helmets or stuffed caps. I understood that in the past few years Gorey had been surrounding himself with mercenaries recruited throughout England, callous men ready to risk their lives against a phantom assassin in exchange for money; their continued upkeep was one of the main reasons for the draining of the baron’s fortune. Hired huntsmen bearing bows and quivers mingled with them in disorder, while the kennel masters dragged the dogs on their leashes. The sight of those lean, ferocious beasts was enough to remind me of the true purpose of that outing, even though no ordinary boar would have justified such a deployment.

I rode on a borrowed horse alongside the Magister, who hunkered on Bess: old hands strangely nimble with the reins. His wooden staff was bound sideways to the improvised saddle fashioned for the donkey’s back. Bess’ dejected shuffling, with that wizened vulture perched atop her, made her all the more miserable as she slugged on through the drying mud. Doubtless a squalid picture – yet the Magister’s eyes glinted with resolve, and bespoke a hidden strength which would give any man pause.

My gaze went beside him and to the baron himself. Mounted on his best warhorse, Gorey rode with clumsiness born of years of laziness and heavy drinking, leaning on the saddle with the considerable weight of his body. He wore a loose shirt of mail rings which his aides had scrubbed clean the night before; under the shadows of his large helmet, I could see the anxious squinting of his eyes. “I don’t like it,” he said again, voice low and hoarse. “Are you sure he will come to these woods, Magus?” I couldn’t say whether the Hunter’s coming was the baron’s greatest hope or fear at this point. Both, perhaps.

The Magister did not even turn to him. “He will come. The Black Dog is Herne’s herald, and where he appears, the Hunt is not far off. Thus, we answer to his challenge, and come to meet him.”

“If we really meet him, he’ll regret it.” Gorey’s marshal emerged from the mingling men to ride at the baron’s side. A lean man with a hawkish, scruffy-bearded face, he regaled me with a gap-toothed grin before turning to his master. He lowered his voice, in a vain effort not to be heard. “The dogs picked up a trail, lord.”

The baron caught his breath. I saw terror flash on his face, and the Magister baring one of his feral smiles. “What are you waiting for, then? Send the huntsmen out.” Gorey wiped his forehead. “I want this done with once and for all. Yes. We kill the assassin now, and I’ll be free. I’ll be…” His eyes met the Magister’s, seeking approval.

The old man stared back, then shrugged.

“Herne is coming. Do as you wish, and it won’t make any difference.”

I clutched at the reins. Of a sudden, the woods seemed darker, the light fading from the moss-covered trunks of the great oaks. The noises of the forest now held an undertone of menace to my ears. Herne is coming, I thought, those careless words ringing in my head. Whispers rippled around me; riders reined their horses closer. The dogs strained at their leashes, fangs glistening with foam. I felt every muscle in my body tense, my stomach clench with nervous expectation. A heavy stillness had settled over us.

The Magister snapped his fingers.

The leashes broke. The dogs shot free like released arrows, bounding amidst shouts and curses. The undergrowth swallowed them, their barking fading in the distance.

“Jesus on the cross.” Gorey was livid. “Follow them, you whoresons! Get on with the chase, for God’s sake – a hundred gold pieces to the one who brings me a head!”

Horses bumped against me as the hunt fanned out in hot pursuit. It was not an easy task to extricate oneself from the press of armed mercenaries, whom the sudden outburst had taken by surprise. At least two horses panicked, throwing their riders to the ground, others lashed out with hooves and teeth as the soldiers’ spears scraped against their flanks. “Magister,” I shouted, trying to reach the old man in the midst of that chaos. But it was hard enough to stay in the saddle as the column scattered and lurched forward. I clung to the reins and caught a glimpse of Gorey swaying on his warhorse, mouth agape and helmetless. He cried something in the confusion, then someone crashed against him. “A hundred gold pieces! A thousand…”

His voice was swallowed by the noise of fifty men whooping and charging. For the following moments, it was as if my senses had vanished, and my world shrunken to the reins and my horse’s neck. The beast reared amidst the chaos, broke free of the human flood pouring into the inner forest without order or direction. The mercenaries had given chase too, lured by the promise of gold and riches, and through that surge it was all I could do to try and stay in the saddle. I closed my eyes.

When I reopened them, our narrow stretch of wood could have been a recent site of battle. The earthen track had become a tangle of flattened mud, the grass trampled and uprooted by the pounding of half a hundred hooves.

Just four men guarded the baron now. Gorey lay sprawled in the mud, his chain mail spattered with dirt and a long cut across the forehead. His horse was nowhere to be seen. He blinked, then bowed his head and retched.

A shocked silence had descended, broken only by the baron’s heavy gasps. The marshal, who had stayed with his lord, averted his gaze. “He’s got a twisted ankle.”

I tried to clear my thoughts. “What just happened?”

“Always unwise to dangle gold too openly before such cutthroats.” The marshal dismounted, took his helmet off and spat. “We shouldn’t have brought the mercenaries. They’re a pack of rabid dogs. Once loosed, they can’t be controlled.”

I could still hear the shouts and imprecations of the chasers, growing fainter by the moment. The pounding of iron-shod hooves faded under the resurgent murmur of the forest, the susurrus of crickets and swaying branches. Still dazed from the outburst, I struggled to regain my focus, sought to isolate my mind from that insectile chant. The swearing and the clanging of armour had already receded into memory, as the woods closed around us once again.

I climbed off the saddle with difficulty. Gorey had managed to crane his neck towards me. Laying in the mud, grunting with effort as he tried to heave himself to a sitting position, he looked like a pale, fleshy worm. “What happened?”, he repeated. “And where is the Magus?”

It hit me with the force of a hammer. The Magister. I’d lost sight of him in the chaos, but he’d been riding with Gorey at the head of the column, straight in the path of the charging horses. Had he been trampled? I dared not look at the ground, fearing, and maybe half-hoping, to see his pulped remnants laying across the track.

“Heh. You’d like that, wouldn’t you?”

I turned, almost stumbling on my own robe. The Magister had emerged from the shadow of the trees behind us, with old Bess shuffling beside him. He was still dirty and bent and ragged, and regrettably alive. Before I could give voice to my surprise, he gave a casual twirl of the cane. I judged silence to be the better answer.

“Magus.” Gorey’s voice came out in a rasping wheeze. “The mercenaries can’t be far. Fetch them back, Will. We need to hunt.” He tried to add something, but had to close his eyes and lean back, overcome by nausea. The marshal turned to go.

“Old I may be, and deaf as a post,” the Magister interjected in a mild tone. “But I have not heard a single hoofbeat for a while now.”

It was true, I realized. More than half a hundred horsemen had scattered across the woods barely minutes before, yet there was no voice, bark, or neighing to be heard. Wherever I looked, I only saw the waving foliage and the trees, their trunks warped and twisted with excrescences by the growth of centuries; the moss covering their roots gleaming jet black in the deepening penumbra. Leaves rustled, and the buzzing monotone of crickets grew insistent.

The marshal stopped in his tracks. I saw his scowl vanishing in disquiet as he hesitated, and took a step back to the clearing. “Lord?” He said, suddenly lost. My head began to throb. “Can’t hear them, lord.”

Gorey shook his head, cold sweat running through his sparse hair. “They can’t be far,” he repeated. He seemed to have difficulty in articulating words. Had he drunk himself into that senseless venture? Yet I could feel the same torpor creeping into my blood as well, my thoughts becoming sluggish. The ever-present drone of bugs and cicadas rang and pounded against my skull, and I felt my legs give out like two sacks of wet sand. Of a sudden, the wet grass brushed my forehead, and I struggled to rise. “It’s the goddamn bugs”, I heard the baron moan.

The Magister shook his head, slowly. His voice rang sharp and clear, cutting through the deepening mist enveloping my mind.

“There are no crickets in Herne’s woods”, he said.

Then the first arrow whizzed past my head, so fast I only saw a black blur flashing by before I heard the marshal’s broken cry. I rolled on my back to see the man standing right before me, mouth agape and swaying. A foot of black ash still quivered, buried in his throat. He was trying to speak, but blood welled up from his parted lips.

Only one of the three remaining guardsmen managed to unsheathe his sword before the woods rang with the thrumming of bowstrings. One man fell clutching his stomach with both hands, a sword slipped from nerveless fingers. Another sank to his knees, barely missing my prone form. The missile had ripped through his thigh, and I saw him try and reach for his fallen blade, wide eyes searching frantically.

His lips set in a tight line, the Magister raised his cane and hit him across the forehead. I heard whinnying as our horses crashed through the undergrowth in crazed fear.

The woods still sang their litany.

“Lord”, I managed. “Magus. Why…?”

Leaves rustled at the clearing’s edge. Tearing clear through my torpor, I heard the cracking of a fallen branch underfoot, the soft noise of wet earth giving up under booted sole or hoof. Something emerged from the darkness, or coalesced from it in graceful motion.

From somewhere far away, I heard a piercing scream.

It was Gorey. “No”, he said, “no, no”, and then terror overwhelmed what was left of his wits and choked his words into a whimper.

The Hunter neared. My nostrils filled with the pungent smells of fresh moss, of resin, of earth black and damp from the long rains, and underneath with the acrid odour of wet furs, and human sweat. Through the penumbra I could scarce glimpse him; an impression of leather boots (of talons now, of caprine hooves an instant later); rippling muscles under patchwork, hairy garb; on his head the jagged silhouette of horns.

Herne turned to Gorey. I doubt the baron could even see him at this point. His mind broken, he squirmed in the mud like a hooked worm, eyes wide to bursting point. The Hunter lifted a hand then, and the woods disgorged a second form. I saw bared fangs and bloodshot eyes. It was the Black Dog.

Gorey’s whimpers had subsided. The baron blinked, Herne towering before him. His thick lips moved with difficulty as he spoke. “Herne”, Gorey exhaled.

I saw the Hunter nod, and as it did so loose fur and leather flapped away from his neck. For an instant, I thought I could grasp what lay beneath its visage.

And I stepped forward.

There was no question that Gorey was damned, and that the Hunter would drag him down to Hell and to just retribution for his sins. But Herne was still a creature of darkness, the alien and malevolent spawn of the Adversary: and Gorey, for all that through his life he’d betrayed his chosen station, was still a man.

My three years with the Magister had taught me some magics less dependent on the Ritual, but my hands were guided by instinct. I felt them grasping the embossed walnut of the crucifix, pulling it from my neck as I held it aloft. Suddenly I could hear the chirping song receding: mind and soul grasped at reality, and found hold.

“Vade retro”, I said, steeling my voice. The old prayers of exorcism came to my lips, Latin turning swiftly to the Greek of the first desert Fathers.

And as I chanted, the Hunter stopped. I saw him crane his horned head at me. Its hand – his tearing claw – rose a few inches and stood in Byzantine crystallization.

Behind me, I heard the Magister sigh.

I inched sideways, reached with my free hand, pulled. The baron was dead weight against my back, forcing me to bend as he slung an arm across my shoulder. I could still see Herne and the Magister, standing among the dead men, watching me in frozen tableau as the clearing receded behind us.

I remember little of the ensuing flight. A mad dash through leaves and brambles, skidding, stumbling over tussocky ground. The woods seemed to tilt, to rush at us as we plunged headlong into the foliage, through trees black and tall as angel sentinels: branches extended crooked fingers, ripping at my cassock and Gorey’s soiled silks.

Then, with one last stumbling push, we emerged. I fell on my knees, breath searing my lungs as I gasped for air, Gorey crumpling to the ground beside me. I blinked, the mangled prayer still twisting my tongue.

What breath I had left caught in my throat. Before us was the clearing, the old man, the felled guardsmen. The woods had twisted our path, shaped it according to whatever doom had been engraved at creation on bark and moss and stone. Back to the Magister; and back to the Hunter.

I looked at the Magister, lost for words. Not unkindly, he shook his head.

Herne moved then; footfalls soundless on the grass. I got back to my feet, standing between him and the baron. The Hunter had the bow in his hand, and the Black Dog flowed like darkness in his wake, fangs bared.

I knew I would not survive this new confrontation, and I steeled myself to a martyrdom for which I had not asked. I lifted the cross, rallying what power my words still held on the creature, and the Hunter raised his bow to nock an arrow.

The Magister’s staff came down between us. I had not seen the old man moving, yet he stood before me now, staring squarely at the Hunter. Herne froze again; the song of the crickets dwindled to near silence.

The Magister once again stood tall, his hump seemingly disappeared within the ragged folds of his grey garment; his aquiline features stark and sombre. He spoke without looking back.

“Another lesson, apprentice. The line between this world and the others is subtle, and oft blurred. Always thread it carefully.” With this the Magister swept his staff outwards in an encompassing gesture, letting its sharpened end rest towards the edge of the clearing where the grass gave way to brush and roots. Then, to my surprise, he bowed his head.

“Gamekeeper of the woods. Great Hunter of the forest and guardian of the Black Goat’s thousand sons.” The staff slashed the earth, tracing signs and curves the outline of which I could not distinguish. “The transgression is repaired, the tort amended. I have brought the prey you seek.” There was a brief pause. “Let not the audacity of an innocent spoil your hard-won vengeance.”

For the longest time Herne watched, planes of shadow given human shape. Both he and the Magister stood extraordinarily motionless, rescinded from space and time like the icons of Theodosian dynasts. Instants stretched into eternity.

Somewhere behind me, a stilted voice came. “Is it really you? After all this time?”

I think Herne spoke then, but his own words were drowned as the deafening buzz surged once again from the trees.

A great tiredness again took hold of me, too strong this time to offer resistance. The cross slipped away from my fingers and my story, clattering down in some faraway place where the forest sang, and a man screamed.

As I closed my eyes and let the wood-song wash over me, I thought I could hear the piping of wild flutes.

5. Epilogue

News of baron Gorey’s death spread like wildfire through the country, and was received by the local farmers and peasants with abundance of good grace and very little sorrow. I say death because I hold no doubt as to his ultimate fate, but the more truthful designation would be his disappearance, for when I came to my senses in the clearing he or his body was nowhere to be found. Departing from the spot where he had lain, I found a tangle of mud and flattened grass, as if someone had dragged a heavy deadweight away. The tracks vanished abruptly where the clearing gave way to the woods; or my skill at tracking was so poor that I could not detect the winding of the trail amongst the trees.

When I came to my senses, the first thing I saw was the Magister sitting on the grass with his back to a tree almost as gnarled and humped as him. “You’re awake”, he grumbled as he took hold of his cane and managed to heave himself upright. “Never should one sit for so long at my age. My bones feel as brittle as a starving Franciscan’s.” He spat on the ground. “Well, I must have fallen asleep. What kind of devil are you, to let an old man shiver on the grass without even giving him a cloak?”

I could barely speak or walk by then, and would remain in that state for almost a day and a night, grappling with nausea and disbelief. Thus, when a group of guards and mercenaries rode in disarray into the clearing, cursing and asking to know where their lord was, it was the Magister who explained to them in brisk tones how the baron had ridden straight into the forest in pursuit of the dogs, leaving a crippled ancient and his helper stranded there alone. The corpses of the marshal and his guards had disappeared too, and even though I noticed a black shaft protruding at some distance from the earth, I chose not to point it out to our unscrupulous friends. The mercenaries eventually rode away, and we later heard they had dispersed in search of easier pickings as the duke’s men-at-arms rode to install the new baron in Gorey’s rundown seat.

The Magister took me by the arm and led me back towards the beaten track, guiding my queasy steps with unaccustomed gentleness. There we found Bess, waiting for us with the stoic patience of the stolid and whittling time away by munching on fresh grass. It must needs saying, ” the Magister sighed at one point,” that I would have liked that gold very much.”

Sunlight slanted across the trees, bathing the Magister’s lined face in liquid honey. “Magus,” I asked again, my steps clumsy as those of a new-born colt. “Why?”

“You do not get to eighty years of age without the knowledge of which fights you can pick, and which ones you cannot.” The Magister looked grave, and I could discern wintry gleaming in his eyes. “Some demons require power to appease them; some wish for gold and slaves. And there are some – the oldest, the forgotten – who command sacrifice.”

The Magister helped me climb on Bess’s knobby back, steadied my feet into the stirrups.

“A single victim to save the whole flock”, he said. “I believe you might find the story familiar.”

We departed from baron Gorey’s castle in the morning of the next day. I still felt feverish, so the Magister helped me to the back of our wooden cart and climbed into my own seat with some difficulty. A terrible handler, he tugged tentatively at the reins and was met with Bess’ resigned bleat as the donkey stepped forward to face the road ahead. It was Sunday in the year of our Lord, and I awoke as the first rays of the sun slashed through my eyelids and the cart shook and trembled into motion.

“Where are we going?”

The Magister gave a mirthless chuckle. “Heh, I do not know yet. South to London, for a start. You’ll have to cut your teeth against more than Saxon boggarts – perhaps we’re going to France, where the heretics nestle, or down to Rome with its ruins and catamites.” He smiled a thin smile. “In any case, apprentice, you are not going to like it one bit.”

I gave a nauseous sigh and closed my eyes again. Crickets chirped in the meadows beyond, bluebells swayed before the rising sun, and we trudged forward into the warmth of a summer morning in Yorkshire.

________________________________________

Francesco Meriano was born in 1994, and has been dreaming worlds ever since. A native of

Rome, Italy, he nurtures an abiding love for historical and fantastic literature. When he’s not lost

in the clouds, he pursues a career in international relations — but he’d rather stay an escapist than

become a diplomat. “The Great Hunt”, first written in 2014, is his first published tale

Miguel Santos is a freelance illustrator and maker of Comics living in Portugal. His artwork has appeared in numerous issues of Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, as well as in the Heroic Fantasy Quarterly Best-of Volume 2. More of his work can be seen at his online portfolio and his instagram.