THE PATH OF TWO ENTWINED, A TALE OF AZATLÁN

THE PATH OF TWO ENTWINED, A TALE OF AZATLÁN, by Gregory Mele

Tehanuwak, the Land of Obsidian and Bronze, is a sweeping vista of ancient city-states in misty highlands and steaming jungles of the deep south to the vast grasslands and burning deserts of unmapped north. At this vast land’s heart lay the Three Empires, proud and ambitious, none more so than that of Azatlán, City of the White Hearth. Ruled by the Naakali, a race of foreign conquerors, Azatlán’s legions push ever outward, seeking to bring more of the world beneath the yoke of the Living Sun.

A young, mixed-race scion of an ancient Naakali family, Sarrumos Koródu answers the call to arms and finds himself captured in battle and offered the glory of an honorable death on a foreign god’s altar. Declining that honor, he escapes home to find himself a disgrace and exile – an anathema to Naakali eyes. Fleeing the Living Sun’s divine wrath, the exiled nobleman gains fame – and infamy – as one of the Sea Wolves that harasses the coasts of Empire and merchant canoes of city-states alike (see “Kamazotz” in HFQ 41 and “Father-of-Rivers”, HFQ 50).

Before taking to sea, Sarrumos sought employment and obscurity among the Korête, fiercely independent Naakali lords, whose fortresses lay scattered along the northern fringe of Azatlán’s empire. Living off petty ambition, these kinglings are constantly at war, both between themselves and the scattered clans of ancient, camelops-riding Kwalankku nomads who have ruled the grasslands for centuries before the Naakali’s arrival.

But the Korête lords, lost in their own ambitions, misjudge the will of the so-called barbarians on their borders, hunting lions and bison and seeking to outdo one another in their excesses, while an ambitious old man seeks to unite the clans – and be rid of the city dwellers, once and for all.

They called themselves Kwalankku, the People of War, though none could remember a time when the Seven Clans had truly been one People. The clans were united only by the Law, the lance, and a belief that there were few things worse for a chieftain than to be old.

Tonight, all these things were on Yiskha Lupan’s mind, for he meant to unite the clans, and he had long-since ceased being young.

Sitting cross-legged before a small fire, he tried focusing on the ritual, but his knees ached, pain gnawed at his low back and his eyes stung from the acrid smoke that filled the small wickiup. He tried to be reverent, not annoyed, as one of Grandmother’s “daughters” shook a tortoise shell rattle around him, calling upon one of the People’s more chthonic gods.

“Mosau’u, Lord of the Underworld!

Awaken from your slumber in the depths of Túwakatsi.

Itzpapá! Mother of war!

Hear our prayers, oh mistress of inextinguishable power,

That we may ride to victory!”

The young woman, stripped to a breechclout, her copper-skin slick with sweat from the heat and her exhortations, used an eagle feather to fan sage and copal fumes over Yishka and his naabaahi – war-leaders – seated with him around the fire, adding to the smoky haze.

The old clan chief wiped agitatedly at his eyes. Seeing his war-leaders sitting straight, reverently murmuring prayers only annoyed him further.

“We have Ahiga, the Ma’iitsoh clan chief, and the Tall Men’s naabaahi. Tomorrow, when Mother Moon rises in Her fullness, their sacrifice will unite the clans and destroy the Tall Men in their camps of stone. All is as you said the gods require, Grandmother. Is all this –” he gestured about the smoky hut in disgust – “necessary?”

Grandmother Nine-Caves was silent, but looked annoyed, as she cast bones on the dirt floor and poked through them. Like all who had guarded Toyataahi’s sacred caves before her, she was called Grandmother, but she had barely seen two-score summers. Scooping the bones up, she cast them once more, chewing her lower lip. She did this several times more before she sighed, gathered them up frustrated, and tucked them away in a buckskin bag.

“You are a great war-leader, Yiskha Lupan, and if you are patient, you will be greater still. But you would do well be to be humble in matters of the gods! The bones show Brother Koyotl is making mischief tonight.”

“Tell that mangy Trickster to keep his snout out of our business!”

Looking up from the bones, she cast her dead eye, the one each Grandmother sacrificed to see between the Worlds, upon the chieftain. “Mock not! It is no easy matter to call Ya’i-tsoh forth; and He is never compelled, only propitiated. Trust me, Yishka Lupan of the Chiniyaii clan, you have lived long and seen much death, but you would not wish to see the death that Ya’i-tsoh brings, should we release him wrongly. The Path of Two-Entwined is a narrow one, and we must tread it carefully.”

The old clan chief opened his mouth to make an angry reply, but he inhaled a gulp of copal and sage fumes that made him cough and hack.

Hearing his discomfort, Grandmother Nine-Caves looked up through her long, bone-woven braids, a wry little smile on her lips. The gods had a way of making Their displeasure known. Taking up her buckskin bag she shook it and cast the bones once more. Now to see if she could discern what mischief the least of those gods was making.

****

Sky Father’s burning eye gazed down over the Kohi River as the lone Kwalankku warrior reined in his camelops before Hashkeh Dighin, a war-leader of the Chiniyaii clan.

The pass was not wide, winding back and forth like Old Man Serpent so that on either hand the red rocks pressed in close. If the pass was narrow, Hashkeh Dighin was broad, looking like a great horned owl as he sat his mount, wrapped in a war-leader’s feathered shawl. A war-leader of the People was never alone, and two warriors were with him now, carrying bows and round, wicker shields faced in deer-hide, their limbs tattooed, and their faces brightly painted. Looking at Hashkeh Dighin’s broad face, painted redder than blood with spots black as night, the lone man shifted on his steed, his hand toying with the copper hatchet in his belt.

The naabaahii watched that hand, then looked back to meet the other’s eyes, his thick lips twisting into a smile that reminded the lone ride of two fat, wriggling worms.

“Hail, Niichaad!” he cried loudly. “What brings one of the Ma’iitsoh clan to Chiniyaii land?”

Fair words were a weapon for those who wished you ill. Niichaad had seen two-score and eight years; too old and too blooded to word-dance with this pompous fool.

“As doubtless as Father Sky sees all, Hashkeh Dighin knows my task. I ride to Toyataahi, where Yiskha Lupan holds Ahiga, my chieftain, prisoner.”

“Niichaad,” the war-chief said, his eyes glittering like obsidian from his blood-red face, “is a warrior of much honor and many camelops. He should turn back from what cannot be undone. Ahiga, bihkéhe of the Mą’iitsoh clan dies three times tomorrow night: A bowstring drawn around the neck, his heart cut from his chest and his head struck from his shoulders.”

Niichaad’s stomach clenched. The Three-Fold Death was reserved for the Law’s most abhorred betrayers, for each death killed the man in one of the Three Worlds, leaving what remained of his spirit to wander the earth forever more, his headless spirit blindly seeking Father Sky’s hunting grounds.

“There is no love between the Ma’iitsoh and Chiniyaii, clans but we are all still of the People. What crime did Ahiga commit that your chieftain abhors him so?”

Hashkeh Dighin’s worm lips wriggled into a new shape: A wide grin that showed square teeth, painted as red as his face.

“Yiskha Lupan does this thing not for vengeance, but for all the People’s glory! We have been as vultures, picking at the Tall Men’s leavings. But no more! With Ahiga’s death, the Tall Men in their great stone villages will know such death as they have never known before!”

Niichaad’s hand slipped about the copper hatchet’s hickory shaft. “The Tall Men rule the coast and the river-mouths; the People are master of the grasslands and the desert beyond. What need have we for the sea, and its endless waters no man can drink?”

The naabaahii‘s feathered shoulders shook with laughter as he looked to the warriors beside him as if to say, see what a fool this one is?

“When Ahiga is dead, a vengeance will sweep out of the grasslands like the hot winds that bring the rain. When it is done, we will be free of the Tall Men, and the People will be one. Why not ride with me now and offer Yiskha Lupan your spear?”

The older man’s voice was like the lion’s low rumble before it sprang. “I am a warrior of the Ma’iitsoh. Ahiga is our bihkéhe, but there have been bihkéhe before him, and will be after he is gone. It is the way of the clans.”

“You still do not understand, Niichaad – when all is done, there will be no more clans, only one People — and Yiskha Lupan the bihkéhe of us all!”

Niichaad said nothing. Clearly, Hashkeh Dighin was mad, but he must pass him if he would reach Toyataahi and the sacred caves that lay therein. They were three to his one, and had bows, while Niichaad had none. He looked at the winding Kohi murmuring softly beside their camelops’ feet, withered to a narrow rivulet with the Dry Season, then glanced up to behold Father Sky’s burning eye watching – judging – from overhead. It was a good day to die, and his cause was worthy. He began slipping the hatchet from his belt, judging which of them was in reach of a throw.

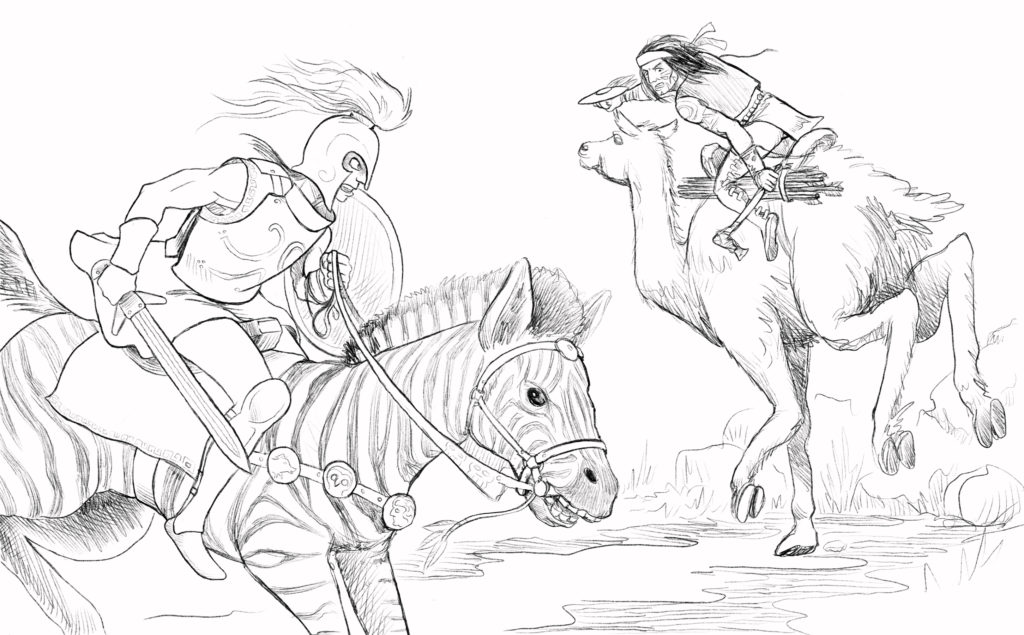

But Hashkeh and his warriors were looking past him, to the path beyond, where two men approached, one astride one of the striped-legged, hornless deer the Tall Men used to pull their war-carts, as if it were a camelops; the other was on foot, using his spear as a walking staff. Niichad turned his mount about and looked upon the newcomers.

The strangers had wide, round shields slung over their backs, and the rider had an arm-length, long-knife at his side. He also wore a metal hat that gleamed golden like the sun above. The walker wore a wide-brimmed, straw hat, and a dusty and tattered tunic. They were both bare-legged but for sandals, as was the southern way. Tall Men. Naakali, they called themselves.

Niichaad had never seen a live Naakali so close, unless they were trying to kill him. He suspected Hashkeh Dighin and his men hadn’t, either.

Seeing the Kwalankku tribesmen, the two Naakali halted where they were, the rider lifting his hand to parlay. Without a word, Hashkeh Dighin urged his camelops slowly toward him, moved by curiosity. Niichaad was tempted to ride with him as he passed but held still.

Seeing the painted war-leader approach, the footman stepped forward and lowered his spear threateningly. His eyes shone wild in his dirty face. Halting his mount, Hashkeh Dighin lifted two fingers of his right hand. Like the buzz of wasps, two shafts sped forth from his warrior’s bows. A wet thud, and fletching blossomed like flowers from the spearman’s throat and chest. He fell where he stood, blood spewing from his mouth, hands pawing at the shafts that had taken his life. With an exclamation of anger, the rider drew his long-knife, its blade flashing golden as it came free of its scabbard.

Niichaad held still, torn with indecision. Hashkeh Dighin was an enemy, whom just moments before he had planned to kill, but he was still of the People. And the one bleeding out his life had been a fool to threaten a naabaahii.

“The Tall Men,” said Hashkeh Dighin loudly, “do not belong on the People’s hunting grounds. Let us cut this one down, feast upon the striped haunches of his hornless deer, then carry his long-knife and metal hat back to Yiskha Lupan as a gift.” His two followers began fitting arrows to their strings.

A middle path came to Niichaad’s mind, and he trotted his camelops forward, to stand beside the burly warrior. “You say your chief will become bihkéhe of all the People, Hashkeh Dighin,” he said quickly. “Will we then forget the Law and become as wolves, setting a pack upon a single stag? Does a naabaahii now send flights of arrows against a single man, rather than blood his own lance?”

The war-leader’s dark eyes flicked to the stranger and back, uncertain and angry. “The Law is for the People,” he hissed.

“Of course. But if a naabaahii no longer finds honor in defeating a single warrior of the Tall Men when he stands alone offering battle, how shall he be known from a common brave? Does his feather-cloak mean no more than a woman’s dress?”

Scowling, the bigger man turned his mount, riding back to his warriors, where he spoke quietly. Then, drawing a long, barbed javelin from a quiver that hung at his right side, Hashkeh Dighin settled his shield on his arm and with a wild war-cry kicked his camelops’ side, riding hard towards the tall Naakali on his more diminutive mount.

The foreigner’s shield was as much larger than one of the People’s bucklers as his mount was smaller, but it hung across his back, and he was still attempting to pull it about as the burly Kwalankku hurled his dart. The javelin flew true and struck the Naakali straight in his chest. Niichaad thought that was the end of it. But there was a loud clang, and the javelin fell away, the stranger swaying in his saddle, but not falling.

Believing his opponent mortally wounded, Hashkeh Dighin turned his camelops back towards his followers, worm-lips spread in a wide smile. Seeing his men pointing behind him, he realized something was amiss, and wheeled his mount about just in time to reflexively catch the Naakali’s first blow on his shield.

The hornless deer were smaller than the massive camelops, but fast and nimble. The stranger had already turned his mount away before Hashkeh Dighin could draw another weapon to respond, and then he was on his flank, slashing at his leg. The war-leader beat the blow aside with his hastily drawn hatchet and struck back. But the short-handled axe was a weapon for throwing or fighting on foot; the bow and lance were meant for fighting astride the Kwalankku’s long-legged camelops. Haskeh had to lean far over to reach the Naakali on his shorter mount, and when he did, the stranger was already riding past, his long-knife slashing out backhanded, leaving a wide cut across the big man’s stout rump.

With a surprisingly high-pitched shriek, Hashkeh Dighin lurched forward, bloodied buttocks making it impossible for him to sit back in the saddle. Howling, his braves leapt forward to his aid. Niichaad reached for his lance and made ready to join the fight; the Law said that when a warrior entered single combat, it was forbidden for others to battle on his behalf. The he remembered that the Law also said that a warrior must defend his naabaahii, and the Naakali was not of the People.

Entering the fray, the two braves used their wicker shields and larger mounts to cover their leader from further attack while he fell back, yet themselves made no effort to fight. Niichaad decided their actions were enough in keeping with the Law that he would not interfere.

Bloodied and humiliated, leaning heavily against his camelops’s neck to spare his wounded bottom, Hashkeh Dighin urged his mount up the ravine. Once he was clear, his warriors quickly followed. Niichaad watched their flight and laughed, for the proud war-leader had squealed just like a stuck peccary.

Kicking his mount’s striped flanks, the Naakali made to pursue, but Niichaad guided his camelops to block the man’s path.

This close, the Kwalankku could see he was a strange one. He was strongly built, but not at all like the Naakali, who were famed for their long limbs: He was no taller than one of the People, shorter than many, and rangy, though his shoulders were broad. His skin was coppery like the People’s, but eyes as green as southern jade and a short, auburn beard said he was no tribesmen. He was also noticeably young; Niichaad doubted he had seen more than twenty-two or three summers. He had spoken in Tekwapu, a language spoken to some degree by the many tribes that dwelt across the Zakatla grasslands and the burning desert beyond.

“No, bold one,” Niichaad answered in the same tongue. “You would be a fool. They would fill you with arrows before you drew close.”

Jadeite eyes glanced angrily up the pass at the retreating forms, then the young man turned and rode back to his fallen companion. Slipping from the hornless deer, he lifted the spearman in his arms. He glanced once at the Kohi River bubbling over the red rocks; then walked up the hillside a few paces where a lone cherry tree grew. Lying the body beside it, he drew a broad bladed dagger and fell to digging a shallow grave between the roots, where the soil was soft and there was no grass.

Niichaad was moved to help, but could not, for the Law forbade handling foreign dead. Instead, he dismounted, took food from his saddlebags and, sitting on the slopes of the ravine, began to eat while the stranger worked.

The Naakali did not cease laboring until he had a hole sufficiently large to fit the body when he curled in the legs, so it lay as did a child in the womb. Once the grave was filled in with dirt, he laid several large stones as protection from scavenger’s determined digging.

Niichaad watched, morosely thinking that each man’s road ended in his grave, but there would like as not be no one to dig his own. He was still meditating upon this when the Naakali came and stood beside him.

“Who was that who ordered my friend slain?” he asked. The Kwalankku warrior told him, and the young man’s face grew hard.

“He shall pay for what he did.”

Niichad noted he spoke as decisively as he had wielded his long-knife.

“Where has this Hashkeh Dighin gone?”

“To Toyataahi. It –,” he tore angrily at piece of deer jerky. It was hard, finding the Tekwapu words for what he meant. “It is a holy place for the People, respected by all the clans.”

He was silent, watching the older man eat. “We only wanted to trade for food. We had not eaten for two days,” he said.

“Then you shall eat now,” Niichaad said, gesturing to him with the deer jerky in his hand. This stranger was not of the People, but brave, and the Law respected courage. The Naakali took the jerky and devoured it hastily, then the sunflower seeds and bean-paste the older man offered besides.

The Kwalankku said nothing, just watched him thoughtfully. Why was a warrior with a tribesman’s body and a Naakali face riding a hornless deer deep in the grasslands, far from his people’s vast stone villages? How had he learned Tekwapu?

“I wish to hold your weapon,” he said as the Naakali finished draining his waterskin, “I have only seen long-knives when they are being swung at my face.”

The young man looked at him warily.

“It is hard to hand my sword to one whose people have slaughtered mine.”

“We are sharing water and meat. The Law of the People says we are as clan brothers unless either you offer offense, or until we part ways.”

The Naakali chewed his lower lip thoughtfully, then drew the long-knife and handed it over. It felt strange in Niichaad’s hand, different from the flint knives he knew; sinuous, like a snake, but still a bit weighty, like a hatchet. In the midday sun, its metal gleamed golden.

“I am Sarrumos,” the young man said. “If we are clan-brothers, shouldn’t I know your name?”

“Sa-Ru-Mos,” the Kwalankku said slowly, turning the sounds in his mouth. “I am Niichaad, a naabaahii of the Ma’iitsoh Clan. I was made so twelve summers ago, when I had this,” he said proudly, pointing to the wide, thick scar on his left breast, “And this,” he gestured to the thin scar that ran over his shoulder, near the thick vein of the neck, “which I had fighting three men alone.”

Sarrumos listened, chewing another piece of jerky, then smiled crookedly. “A naabaahii leads men. Where are yours?”

“Ahiga, our bihkéhe, wished to fly his hawks. At such times he prefers to ride with only a few warriors. The Chiniyaii came upon us at a well and took the bihkéhe captive. It was a very great crime, for wells are sacred. Only I survived and pursued them.”

“And the…Chiniyaii…are also Kwalankku?”

“Yes. We sit on their hunting grounds. It was their naabaahii – war-leader – you fought. But why is one of the Tall Men here, on Chiniyaii land, alone with only a servant?”

Sarrumos’s eyes fell. “He was not a servant, but a friend. A soldier, like me.” He showed the tear in his tunic, where the older man could now clearly see the metal beneath. “The bronze gets hot in the sun, so I covered it with a tunic. My story is strangely like your own. We were guarding the Lord Katelos, our Wannax’s… bihkéhe‘s, as you say…younger brother. Like your chief, he loves to hunt, in this case lions. By chariot.”

Niichaad’s eyes grew wide, but he bit his tongue. The People feared nothing, but they respected great warriors, and Killer-of-Camelops was the greatest of warriors that went about on four feet. He knew not what a ‘chariot’ was, but only a fool would try hunting the great cat for sport.

“We never found a lion, but death found us. A band of Chiniyaii fell upon us, and their first business was slaying the lord’s chariot horses. They outnumbered us badly…it was not so much a battle, as a slaughter.”

“Yet you live.”

Sarrumos flushed in embarrassment and leaned back against the rocks. “I was… answering a call, squatting in the tall grasses as the battle began, and its outcome was clear long before I could join the fight. I remained where I was, and saw them take the Lord Katelos away, to the southwest. I found one survivor, and together, we set out in pursuit.”

“It seems Brother Koyotl protected you with His clever tricks and turns,” the older man said. Then a wide smile spread across his face. “Before you set out, did you remember to wipe your ass?”

Sarrumos laughed, a warm, lively sound in that lonely place, beside a dead man’s grave. “I did, friend Niichaad. I did indeed.”

* * * *

Having decided Brother Koyotl had brought them together, Niichaad lit a pipe that they might together smoke tobacco in the spirit’s honor. And as they smoked, they concluded that the captivity of Ahiga, chief of the Mą’iitsoh clan, and Katelos, brother of the great Wannax of Hemlachál pointed to some greater scheme, which bode ill for Naakali and Kwalankku alike.

“It was the Sky-Father’s will,” Niichaad explained to Sarrumos, “that this heaviness should be laid upon us. No man may escape his fate.”

“But why should this Yishka Lupan believe these things will come to pass? Why would your clans bow to his rule?”

“Pah!” the older man said angrily, “The People are never ruled; they are led! But you must understand that Toyataahi is no natural place; it is a holy place, sacred to all the People, where the earth reaches up to touch the sky. Within are nine caves; seven are where the mothers and fathers of the seven clans dwelt before Killer-of-Monsters made the earth safe from the Alien Gods. The People return each midsummer to make offerings to the ancestors, but between those times it is home only to Grandmother Nine-Caves and her daughters, who speak to the spirits for us all. Deeds done at Toyataahi with her blessing are done with the blessing of the gods Themselves.”

Sarrumos, swatted at a hornet that was buzzing his ear, and nodded unhappily. This place was apparently a temple, with a priestess and her assistants to attend it. He’d had nothing but ill luck from temples and priests.

“So, you are going to Toyataahi, alone,” he said slowly around the pipe, as if he were chewing the tobacco rather than smoking it, “to try to save your chieftain by stealth before he can be executed?”

“The Law is clear: We are the People of War. We take, we do not ask. We accept what the Sky Father wills, and do not weep for more. We give the dead unto Death and leave Life for the living.” Niichaad intoned rhythmically. He had clearly recited it many times over. “No man escapes the fate the gods have adjudged for him. Ahiga dies tomorrow night, but he shall not go unheralded by his warriors! I will ride to Toyataahi and defy Yishka Lupan of the Chiniyaii! I will call out to Grandmother Nine-Caves and say she is a false prophet if she aids in Ahiga’s murder. And I will slay more than my number, before I am slain. Thus, Ma’iitsoh honor will be preserved.”

Sarrumos shook his head. “I have learned not to trust in fate, prophecies, or gods. Your lord lives: If you believe your destiny lies with Ahiga, you must try to save his life.”

“I cannot do what cannot be done!” Niichaad spat, turning away angrily. He lay back on the stones and watched the white flecks of clouds moving across Father Sky’s blanket, swatting angrily at a pair of tree hornets that buzzed persistently about his face.

“What manner of place is Toyataahi, Niichaad?” the Naakali asked.

The older man turned to look at him. “Why should it matter?”

“Because I swore to rescue the Lord Katelos, and I have no intention of dying in that self-indulgent brat’s stead, nor on his behalf.”

“I see the Tall People do not give their bihkéhe and naabaahii much reverence.”

“Rarely enough,” Sarrumos agreed thoughtfully, “but the men of Hemlachál are not my people, nor is Lord Katelos a bihkéhe; merely one’s younger brother. You describe Toyataahi as a great table-rock or mesa. Can the sides be climbed?”

Niichaad shook his head, then swatted suddenly at his long fore-braids.

“Damn these hornets! They must have a nest nearby! The cliff is the height of many long-spears, and too sheer to be climbed.”

“Then we will need to find a way into the caves.”

“It is forbidden under the Law for those not of the People to enter and live!”

“Did you not say that, as we have shared meat and water, we are brothers until we part ways?”

“Yes, that is the Law, too.”

“And you are of the People, yes?”

The older man scowled at the combination of the younger’s endless questions and the inquisitive hornets’ buzzing. “Of course!”

Sarrumos smiled crookedly. “Well, then for now I am ‘of the People’ as well. I had best just make sure we do not part ways until after tomorrow night’s work is done.”

The older man frowned. This seemed more than the Law allowed, but perhaps there was wisdom in not debating that too closely. He swatted away another hornet, was stung for his troubled and winced. “Then you can die with me as one of the People.”

“No, my new friend, we are not dying.” Green eyes narrowed and he tore loose some of the scrub grass, which came free in a little tumble of dirt and dust. “The grass is dry.”

“It is the Dry Season; there has not been rain in over a moon. So?”

“So,” Sarrumos said, snatching a hornet from the air as it tried to land in the other man’s long hair. He held open his hand and showed the crushed insect within. “By that, by this fellow’s brethren, some river mud and an abundance of mad folly, we might just save my pompous lordling, your clan chief and have our revenge before tomorrow night is done.”

“Grass and hornets have given you a plan?”

“Aye. Though only time will tell us if it is a good one.”

Niichaad sat up and listened, the pipe forgotten, its tobacco burning away, an offering to the great gods above.

****

Mother Moon rose into the sky, her silvery gaze shinning down upon the slopes of flat-topped Toyataahi, which rose from among the smaller rock formations like a fortress of rust-red stone; a lonely sentinel standing guard over the vast plains.

Few could match the People of War when they sat astride their long-legged camelops, but afoot was another matter, and Niichaad’s legs felt each of their two-score and seven years by the time the two men gained the precipice of a nearby ridge, looking out across the grasslands beyond.

About the base of the great rock formation were the small gleam of campfires; the host of Yiskha Lupan gathered at the holy place awaiting their bihkéhe’s promised miracle.

“It is hard to see from this distance, but it looks as if they have set guards, and no small number of them,” Sarrumos noted, pointing to various spots in the distant camp.

“Hashkeh Dighin would have told them I was coming,” Niichaad said, his voice bristling with pride, “It is an honor to my name that they do all this on my account.”

The younger man, who was sucking at a pair of raised hornet-stings on his left hand, turned to look at him and sighed.

“Yes, well, we need to get past that ‘honor,’ lest it fills us with arrows.”

The Kwalankku’s grin faded. “True.”

The moon rose higher, until she stood nearly straight over-head.

“It is the beginning of the second watch,” meditated Sarrumos. “I suppose the path down this hill is no better than that ascending it?”

“Path?”

“Let me put it another way: Can you make it down this hill without killing yourself?”

Niichaad’s eyes flashed angrily through the black and white war paint he had applied that night, dividing his face in twain. “I’ll do my part. You do yours.”

Sarrumos winked, “I will see you within.” Then he turned and crept back down the ridge to where their mounts waited.

****

A pair of warriors in deerskin breechclouts and thigh-length moccasins, their bodies painted in black and red slashes, laid the barely conscious Naakali aristocrat across the flat stone altar. Naked, his skin was dusted white, his lips and eyes painted black, but he made no effort to fight, seemed barely able to comprehend where he was or what was happening.

Torches and fires scattered along the cavern’s ledges and crevices provided the only light so that when Grandmother Nine-Caves shook her tortoise shell rattle, arms raised high, eerie, distorted shadows flickered on the back wall.

“Mosau’u, Lord of the Underworld!

Awaken from Your slumber in the depths of Túwakatsi.

Itzpapá! Mother of War!

Hear our prayers, oh Mistress of inextinguishable power,

That we may ride to victory!

Ye’i-tsoh, You are the Earthbreaker!

Born of Stone and Sun; begotten, then abandoned!

We recall You; we know Your name! Ye’i-tsoh Lai’ Nayai!

We honor the Lord of Red Ruin!”

Nine Chiniyaii warriors banged slate rocks against the cavern floor. “Ye’i-tsoh! Ye’i-tsoh!” they hollered and wailed.

Meanwhile, Yiskha Lupan slowly bent his boney frame over the victim laid out on the stone altar and pushed a claw-like fingernail into the man’s chest. “Ye’i-tsoh Lai’ Nayai,” he whispered, “I give you to the Lord of Red Ruin.”

While the chieftain lifted the heavily sedated Naakali lordling’s head, cradling it with one arm beneath the neck, Grandmother Nine-Caves poured a vile liquid into the victim’s mouth, pinching together his nostrils and violently rubbing his throat until he had swallowed the concoction down. Almost immediately, the young man convulsed on the cold, stone slab.

Holding up a needle-sharp point of red obsidian, the shamaness began cutting into the victim’s flesh at the top of the skull between his parted, loosely hanging hair. The drugged Naakali jerked, and his eyes rolled up into his forehead, as she sliced down through the middle of his face. The blade continued down, over his nose, parting his lips, and then his chin, separating his face in two.

“Ye’i-tsoh Lai’ Nayai,” Grandmother Nine-Caves cried, “Descend upon us through this sacrifice.”

She continued slicing the man’s throat and down his chest, blood filling grooves carved along the edges of the stone altar, flowing toward the four corners where urns waited to capture its sacred essence.

Behind them all, Ahiga, the Ma’iitsoh chieftain, struggled against the four men who held him tight, as a pair of women rubbed him with jojoba-seed oil. He watched in disgust and horror as Grandmother Nine-Caves leaned over to kiss the ruined face, then rose, her face stained in the dying man’s blood, and approached him.

“Witch! Traitor! You betray Killer-of-Monster’s Law!” he croaked hoarsely.

The shamaness shook her head, face grave.

“No, Ahiga-bihkéhe. The Law no longer serves the People. It is our destiny to rule the wide grasslands and the burning lands beyond. But that will only come by accepting it is time for a new Law; a Law for one People, not seven.”

The aging warrior spat at her, but his spittle fell short of the mark. “And to do this you go to your knees before Yiskha Lupan? Traitor! Whore!”

Grandmother Nine-Caves looked over her shoulder, to where Yiskha Lupan had taken an obsidian ulu and commenced flaying the victim as he would a deer, the heavily sedated Naakali’s body writhing violently.

“Truly, Yiskha Lupan is a vulture among men. But he will do what must be done. And he is old: What he sets into motion, younger, better men will lead to fruition.”

The shamaness stepped forward and kissed the bihkéhe’s forehead as a mother—a grandmother — might a child she was sending off on a journey.

“I am sorry you will not live to see it.”

****

For Niichaad it was an evil half hour, picking his way down the hill. His moccasins slipped in the scree and only a quick thrust of his spear into the ground kept him from tumbling head over heels to his death. Shortly thereafter, he did slip, falling on his back and sliding the length of two spears, his descent checked by slamming painfully into a stunted tree. Bruised in body and pride, more than a little skin peeled from his back, he at last reached the bottom of the hill.

The moon was almost directly overhead, and he could see the mesa plainly, some five bowshots away. Chiniyaii campfires gleamed; from here he could hear muffled voices and the moaning and bleating of the warrior’s camelops. Niichaad settled down in the tall grass; one more night predator waiting for his prey to make a mistake.

His feet were starting to go numb from crouching when he saw an orange glow rising from the south, and soon after, heard the sentries crying out.

“It is the enemy,” someone cried. “Ahiga’s men have set the grass a flame!” There was a flurry of activity, as warriors raced to untie their mounts. Fire was a familiar and terrible foe on the grasslands, whose destruction could rage in all directions if it were not swiftly contained.

Niichaad had been uneasy with this part of Sarrumos’ plan. If the fires burned too hot and too long, only Grandfather Thunder’s rains would contain them — they could just as easily spread to Ma’iitsoh land, which is why the People did not set fire to the fields when they made war on each other. But the foreigner had persuaded him, and now was the time to act, not to fret like an old woman. Snatching up his spear, he slipped towards Toyataahi.

The Chiniyaii had built their camp a respectful distance from the great hillside’s base, and Niichaad had to break from the cover of the tall grass to race towards the mesa, but one more warrior running, spear in hand, drew little notice in the chaos.

Having been to the midsummer rituals many times, he knew well the entrance to the Nine Caves. He ran for it directly, then skidded to a halt as he saw a hulking warrior guarding the jagged rock entrance, a long spear in his hands. A second brave stood just past him, half-hidden in the shadows.

“Intruders!” Niichaad cried quickly, lest the guard become suspicious. “Where is Yiskha Lupan?”

“Where else should he be, but with Grandmother, in the Ninth Cave?” the guard snapped.

“Yes, but there is an attack –”

“Did you not hear the bihkéhe’s words before he left us? Nothing, not even all the other clans riding against us at once, must disturb him.”

Men and camelops alike were crying out now, their voices and bleats echoing off the cave entrance walls, as the first whisps of smoke wafted nearby.

“Doubtless he is guarding Ahiga,” Niichaad said with false calm.

The guard’s eyes narrowed. “Guarding? Are you mad, or –”

The clattering of camelops from the camp beyond grew louder. Sarrumos’ plan had borne fruit: While the eyes of the Chiniyaii were turned to the fire and smoke spreading across the plain, none were turned to the ragged gorge that cut into Toyataahi’s base, revealing the sacred caves within.

There were only the two warriors, and Niichaad knew there was no time for challenges or boasts. He hurled his lance at the first man and was already drawing his hatchet and knife as it pierced the sentry through the hip socket. As he staggered back, Niichaad’s copper hatchet bit deep into his neck through the shoulder muscles. His companion let out a cry of alarm, but it was lost in the shouts of men and animals that rang out from below. Wordlessly, the Ma’iitsoh warrior hurled himself at the man in a whirlwind of copper and flint, which soon was filled with sprays of blood.

Niichaad doused the torch that burned in the cave mouth and dragged the bodies deeper within, hoping that, in the chaos, the shadows would provide enough camouflage to finish the night’s business.

Crouching in the cave mouth, he waited and watched the plain. Beneath the moonlight rose a haze of smoke and dust, towards which Yiskha Lupan’s warriors were swiftly riding. Time was short – when they realized there was no enemy war-party about, some would certainly stay to fight the fire, but the rest would return to Toyataahi to find the intruders.

After what seemed to Niichaad’s racing heart like an eternity, he saw a dark figure outlined against the cave mouth, a large burden humped over one shoulder onto his back. The warrior hefted his spear and began rising from his crouch in one motion, his arm drawing back in one, smooth motion to cast…

…then he saw a glimmer of gold as firelight from the camp beyond reflected from a Naakali war-hat.

“You were long in coming,” he whispered harshly.

“Yes, well, I underestimated how fast a grass fire spreads – and therefore how far I would have to double back to ride behind it so I would not be seen. I’m here now, and,” he lightly patted the saddle-bags draped over his shoulder, “I made it back with these intact. Now, do you have any idea where they may keep your chief and my prince captive?”

The shrug he received in reply was not reassuring.

“There are nine caves within Toyataahi,” Niichaad whispered. “One for each of the seven clans of the People, one for the great ceremonies of the gods…”

“And the last?” Sarrumos asked.

“For the Alien Gods.”

“That sounds…comforting,” the Naakali said with a frown, “Is that where we will find them?”

“Yes.”

“And you know the way?”

Niichaad shrugged. “I have never seen the Ninth Cave, but it is said to be entered from the eighth. And the eighth I know.”

“That is more than I know. Lead on!”

The Kwalankku led his companion through a twisting series of natural passages and wide caverns, lit by scattered torches that hissed and spattered with burning camelops fat. The cavern walls were painted in bright colors, depicting the various clans of the People and their history. They came to a small hollow that required them to crawl through, and Niichaad proclaimed this the entrance to the Ninth Cave. As they scrambled through the low entrance, voices could be heard, one calling out in chant, many answering in refrain:

“Ákoo iͅiͅee Naaghéé!

Neesghánén nahín jaajná’a.

Áí ‘it’ah naaheͅeͅtaa.

Án yoon ndii’ágolaan:

‘Dáandi ‘iͅiͅee Kwalankku bikéyaadaal.”

Nahiilindiná’a.’”

“When the earth had been made, Killer-of-Monsters brought the People forth, from the place beneath the Flat Mountain,” Niichaad intoned, translating, as the men regained their feet. “He said: ‘That which lies beyond this mountain will be the land of the Kwalankku forever.” He looked to the younger man, “It is a recitation of the first Kwalankku, the one who bound away the Alien Gods and made the land safe for the Fathers of the People.”

“Ye’i-tsoh! Ye’i-tsoh!” came many voices in response.

“And that?” Sarrumos asked.

Niichaad looked worried. “The name of one of the Alien Gods.”

As if in confirmation of his words, the cave floor itself seeming to rumble in response.

“That can’t presage anything good,” Sarrumos whispered.

They soon entered a giant cavern of uneven stone, stalactites hanging from the irregular ceiling, creating the feel of a melting place. Light flickered off the walls of the immense cavern from a multitude of fat-soaked torches, whose flickering light and acrid smoke cast dancing shadows upon the stalactites and dimly illumined ancient wall-paintings of predators mundane, and decidedly not-so. There was a fissure in the wall that must reach to the mesa’s roof high above, for stars could be seen, their twinkling light warring with the silver glow of Mother Moon as she slowly hove into view. But the moon and stars were not what caught the men’s eyes.

In the center of the cave was a sprawling firepit, in which a clay cauldron bubbled, stirred by two elders, one male, one female, their wizened bodies nude but for black and white stripes of paint and horrific clay masks that transformed them into caricatures of men.

A woman, decorated with seedpod rattles, deer-tails and chia-paste paint stood in front of the firepit, facing nine warriors in the full panoply of Kwalankku braves who knelt unknowingly between her and the two interlopers. A shawl of camelops hide covered her head, but from beneath it tumbled long, cornrow braids of raven-black hair, lightly streaked with gray, each braid woven with human finger-bones. Blood splashed her hands and lips.

A tall man, his aging body still fit, leathery skin glistening with oil, stood naked behind her, long, grey hair loose about his face. The scalp along the part of his long hair was painted a vibrant red. He was held in place by four men wearing painted masks made from dried pumpkins, a mane of dried grass reeds protruding in all directions.

“Ahiga-bihkéhe,” the older warrior said, starting forward. But Sarrumos grasped his shoulder and pressed him down.

“Not yet! Too many players have not yet appeared, and my plan is limited in its effective range.”

“The woman is Grandmother Nine-Caves,” Niichaad whispered. “She is supposed to be Keeper and Oracle of the Law. Grandmother never takes part in war between the clans. This is an ill thing she does here.”

Sarrumos blanched at the word oracle; he had had his own share of misfortunes with supposed prophetesses. He opened his mouth to speak, but just then, Niichad pointed out a hunch-shouldered, bony man in a wolf-skin cloak, singe-tipped eagle feathers and a multitude of amulets hanging from his loose, white hair. He wore a lion’s claw necklace and anklets of seedpod bells. The wolf’s head on his cloak cast shadows over a craggy face painted completely red except for a black ash band across his eyes, exaggerating high cheekbones and a beak-like nose. His wiry, tattooed arms were splashed to the elbows in blood.

“That is Yishka Lupan,” Niichaad said sourly, “Such foulness is what becomes of a war-leader who lives too long.”

Between clan chief and shamaness lay a long table-stone, upon which a gruesome slab of exposed musculature and tendons gleamed redly. From here, they could make out few details, and Sarrumos made himself look away to begin untying his saddle bags. He carefully pulled out three large, egg-shaped mounds of hardened mud. The “eggs” vibrated with a low hum.

“Remember, we need to get close, without being seen for this to work.”

Niichaad nodded and reached for one of the eggs. He glanced back to the ritual and, hardened warrior of many battles that he was, wished he never had.

Hearing the older man gasp, Sarrumos followed his gaze and watched in horror as the old crones drew from the cauldron what was clearly a human hide rinsed clean of blood and fat. They lifted it out as one might a cape and brought it before Ahiga.

“To-hueeeeen-yo,” Grandmother Nine-Caves chanted. “To-hueeeeen-yo. Mighty Ye’i-tsoh, Heart-of-Stone, hear our prayers! The first sacrifice is made; we don the skin of our enemies!”

“Ye’i-tsoh! Ye’i-tsoh!” the warriors hollered and wailed, beating stones against the ground, which again seemed to tremble and shake with their cries.

The young Naakali stared, horrified, his stomach backing up into his throat, as the two ancients forced Ahiga’s arms through the sleeves of the carnal cape, so that the victim’s split face and long hair hung about his shoulder blades and down his back. The hollowed-out legs and empty feet dangled below. Sarrumos gagged. Imperial Naakali priests routinely tore out men’s hearts atop the pyramids of the sun, and bled maidens to death to water new fields in the Lady of Maguey and Maize’s name, but this…

“That…was…Lord Katelos…,” he whispered. “We…must do this…now,” he said, swallowing hard, his eyes riveted to the horrible seen below.

The older man said nothing, merely nodded as, together, the two separated and began moving among the stalactites and rocks, a pair of stalking shadows in that place of blood and shadow.

Meanwhile, the ancient pair walked among the warriors, smearing the kneeling braves’ arms and legs with the blood of the sacrificial victim.

“Ye’i-tsoh!” Grandmother Nine-Caves intoned, holding her blood-soaked hands aloft, tossing long braids from side to side as she swayed with religious fervor. “In the four directions, I cry your name! From the Fourth World, to the Three that were before, I call you! You whom no man can know, hear me! We pay the price; we seal the pact; we walk the Path of Two-Entwined! Dressed in the skin of thieves, painted in the blood of our enemy, we offer a hero of our people – through our suffering, let the Tall Men suffer; through the death of our great ones, let their own bihkéhe go down into death!”

The ground rumbled and shook once more. Yishka Lupan began winding a bowstring taut over each of his hands, forming a garrote.

The male elder was painting a kneeling warrior in sacrificial blood when he saw Niichaad stepping out of the shadows and offertory fumes. His eyes grew wide within his mask, as the aging warrior lifted his clay bundle aloft and hurled it straight at him. It struck the old man and shattered, a black swarm of buzzing, stinging fury filling the air.

“Niichad, now!” Sarrumos cried.

****

As clouds of hornets stung and swarmed about the warriors, Niichaad charged grimly forward, his entire focus on his chief, who struggled now to pull free of the four masked men still holding him close. There was a movement at his side, and his flint-tipped spear flicked out, sank deep into the place where the hip and thigh met, then, having drunk its fill slid free as the warrior drove forward. He was aware of Sarrumos to his left; the Naakali having shifted his large shield to his arm, long-knife in hand, drove hard into the warriors; his revulsion at this blood-soaked rite transformed into rage. A shield-rim struck hard into a mouth here, a brazen point found a throat there, killing the Chiniyaii braves as they struggled to understand what was happening.

Niichaad’s goals were simple: To free Ahiga, and to ram his spear deep into Yishka Lupan’s shriveled husk. Anything that interfered in those goals would die. The second of those goals had not lived so long, however, without an almost preternatural sense for his own survival. Seeing the two warriors charging in out of the shadows, he gripped one of Grandmother’s assistants and hurled her directly into Niichaad’s path, then fled back into the shadows. The naabaahii leapt aside of the tumbling woman, his eyes seeking the fleeing chieftain.

“Forget him!” Sarrumos shouted, “The witch! Silence her.”

Sound advice had Niichaad not been raised from the cradle to revere Grandmother Nine-Caves — whatever woman currently bore that name — as inviolate. Using the heel of his spear to parry aside a copper-bladed knife, Nichaad turned to his left and plunged its point into a pumpkin-masked face. Feeling the flint stick in the skull he abandoned it, immediately filling his hands with knife and hatchet. Only the shamaness lay now between he and Ahiga-bihkéhe, who struggled in the grasp of the three remaining men. Niichaad hesitated, unable to cut her down.

Grandmother Nine-Caves glanced over her shoulder at him, then turned back, continuing her invocation to Ye’i-tsoh, her voice hurried and hoarse as she struggled to complete her rite, an obsidian knife raised on high. Niichaad might not be able to make himself strike the shamaness, but Ahiga, whose life was about to be sacrificed, was past any such compunctions; he ceased struggling against the warriors and instead lashed out with his foot, stomping Grandmother in the belly, so that she stumbled back, doubled over, and collapsed to her knees, the knife tumbling from her hand.

“Warrior,” she cried, hand outreached to Niichaad from where she lay on the stones. “Ye’i-tsoh will rid us of the Tall Men forever, but to be rid of an enemy chief, we must offer one of our own. If you love the People, strike now!”

Niichad looked at Grandmother Nine-Caves, greatest of the People’s shamans, and his knife thrust out; not at her – even now he could not kill the keeper of their holiest place – but straight through the pumpkin mask of one of Ahiga’s captors.

The man fell where he stood. Wrenching his arms free of his two remaining captors, Ahiga leapt back from their grasp. He hurled the horrible skin-cloak from his shoulders as Niichaad lunged out at one of the other masked men, but they were already turning and fleeing. The warrior might have pursued, but with a strange groaning sound, the cave floor shuddered and trembled once more. He let them flee, and turned back to Ahiga, who had snatched up the shamaness’s knife and was looking down at her with murder in his eyes. She said nothing, only lifted her chin defiantly, baring her throat, daring him to strike.

Gripping his chieftain’s arm, Niichaad shook his head.

“She is Grandmother Nine-Caves. Leave her.”

Ahiga’s eyes flashed, his nostrils flared, and for a moment it seemed he would not heed his warrior’s words, but then a shout broke the tension between them.

“We must go!” Sarrumos cried. Having pinned a warrior to the wall with his shield’s rim, he drove his blade’s point up under the man’s ribs. “Now!”

“No! Yishka Lupan –” Ahiga snarled

“He has fled. Kill him another day! Come!” the Naakali cried, as he turned and began trotting back toward the entrance.

Ahiga had no idea who this strange man in bronze who spoke Tekwapu was, but he saw the wisdom in his words. Pulling his arm free from Niichaad he nodded, then turned and raced after Sarrumos, long, loose hair flying out behind him.

Niichaad paused only long enough to look down at the shamaness where she still lay, “I love the People – and will follow their Law to the end, even if you have not.”

Then he was gone, leaving Grandmother Nine-Caves alone with the dead, Katelos’s skinned corpse turned towards her, the lordling’s exposed teeth and eyeballs mocking her with its hideous, unseeing grin.

****

As they stumbled out of the caves into the night, Niichaad took a deep breath – and immediately began to cough and gasp, the air thick with smoke from burning grass. The first of Sarrumos’s ploys still plagued the Chiniyaii war-band, and it seemed the riders would be forced to abandon their attempts to corral the flames and let them rage until the Grandfather Thunder saw fit to douse them Himself.

Of Sarrumos himself, there was no sign.

In the hellscape of smoke and trembling earth, few took notice of the pair of blood-spattered warriors, one of them stark naked; those who hesitated to look more closely found themselves at the wrong end of hatchet and spear. Soon, the two men had captured a pair of camelops, and, though it was a struggle to keep the smoke-maddened creatures calm enough to mount, once they were astride it was only too easy to persuade them to gallop away from the fire and smoke.

Once they were clear of the chaotic camp, Niichaad slowed his mount and turned in the saddle, looking for some sign of Sarrumos, but he was nowhere to be seen. He hesitated, unwilling to leave his new ally behind, but his first duty was to get Ahiga free of Toyataahi.

“Why does my naabaahii hesitate?” the clan chief asked, slowing his own mount.

“The one who was with me, without whom none of this would have come to pass,” Niichaad explained. “I think he still lives.”

“Then by the Law, we wait,” Ahiga said stoically, though he slumped heavily against his camelops’ broad neck.

Moments seemed like hours as they stared back at the mesa, the fires having spread nearly to its base. The ground continued to shake and heave, and the sky rang with thunder – Niichaad wondered if the sound was really the echoing of the earth’s paroxysms, for the sky remained clear, Mother Moon and Her attendant stars still watching impassively from above.

Just as he was about to tell his chieftain that they should wait no longer, he spied a shape racing towards them across the plain, the hard-running mount clearly no camelops. Sober and taciturn by nature though he was, Niichaad could not suppress a whoop of delight.

“Truly the gods favor madmen,” he said, smiling.

But his smile was short-lived.

Sarrumos galloped towards them, bent low over his mount’s stiff, spiked mane, the tall, flat top of Toyataahi looming up out of the smoke, its steep sides quaking as the earth trembled and heaved. The smoke drew higher, coiling and twisting like a vast serpent, that filled the sky, and as the stars winked through it, Niichaad had the odd thought that they suddenly seemed wrong…misplaced…the moon Herself juxtaposed with another, impossibly large and tinged blood-red.

The great mesa’s outline was itself blurring, transforming…its rocky sides become a scaly hide of flint: Sharp stone knives covering an impossibly vast hide. Agate and turquoise, whiteshell and quartz glittered and shimmered in the moonlight above, and the spreading flames below. But in the vision — surely it was a vision, and not reality — they were not mere precious stones, but the strange agate eyes of an even larger, more terrible and alien figure rising from the earth.

“Ye’i-tsoh,” Ahiga gasped beside him, and then Niichaad knew it was no trick of his tired eyes, but some terrible joining of the People’s world with a far more primal and fearsome one, in which Toyataahi was no mere hillock, but the body of a strange and terrible stone god. The two Kwalankku, strong, brave men, hardened by a lifetime of raid and war, watched, dumbstruck, jaws agape, trembling like frightened children, as the holy place of the People unfolded into an impossibly vast giant whose striped head towered high into the night sky.

Then, the fearsome titan was fading, translucent, the night sky appearing through its vastness as the mundane form of Toyataahi reappeared, reasserting itself, reclaiming its place —the place of men. The ground heaved, thunder clapped, and a vast column of smoke rose high into the air and billowed forth; the thwarted titan’s angry breath, chasing after Sarrumos on his galloping horse.

Ye’i-tsoh was gone – and so was Toyataahi.

“What are you waiting for,” Sarrumos, now almost upon them, shouted. “Ride as if all the Nine Hells were after us!”

In truth, Niichaad thought, perhaps they were.

****

They rode until the sun burnt away the night as surely as the fire had the grass. When Father Sky blessed the world with a new dawn, they found a small grove of firs by a stream where they could dismount and collapse wearily on the ground. Only now did they have the time for Niichaad to introduce his young ally to his chieftain, or to explain the strange fate that had brought them together.

“Ya’i-tsoh is an ancient god; from a time before the People dwelt beneath the sky,” Ahiga said when all had been told. “Grandmother Nine-Caves was mad to try and bring Him forth; may we never know what might have been had she succeeded!”

“And now both Grandmother and the Nine-Caves themselves are gone.” Niichaad said solemnly.

“And many Chiniyaii warriors with them. Perhaps not Yishka Lupan, though,” Ahiga said with a grimace, “that one seems blessed by the darkness itself.”

“Tonight has been a time of gods, both light and dark,” said Niichaad. “Grandmother abandoned Killer-of-Monster’s Law to invoke Ya’i-tsoh. It is said that Brother Koyotl is both the messenger of the Alien Ones, and their jailor, so perhaps He intervened.”

A small, tired smile came across Ahiga’s face. “Perhaps. Truly, our new friend Sa-Ru-Mo is as cunning as Brother Koyotl himself. Hmm… yes! Among the Ma’iitsoh we shall call you Ichtapu.”

Seeing Sarrumos shaking his head in confusion, Niichaad smiled.

“Ichtapu is one of Brother Koyotl’s many names among the People. It means, ‘the Clever’. A good name, eh?”

“Ichtapu…the Clever,” The Naakali thought about that and then nodded. “A far better name than many I have been given since leaving home.”

“Perhaps my bihkéhe names you this too soon. After all, you risked all our lives when you tarried at Toyataahi.”

“I failed Katelos, but I still had business with Hashkeh Dighan,” Sarrumos said. “He owed me a life.”

“Did you find him?” Ahiga asked, watching him warily.

By way of answer, he young Naakali, who was lying beside him, rose and went to his hornless deer – horse, he called it – and rummaged in the saddle bags. He withdrew a bloodied feather-cloak, wound into a ball. He threw the bundle to the ground. It landed heavily and flopped open, disgorging the severed head within.

“Indeed, I did.”

________________________________________

Gregory D. Mele has had a passion for sword & sorcery and historical fiction for most of his life. An early love of dinosaurs led him to dragons, and from dragons…well, the rest should be obvious. From Robin Hood to Conan, Elric to Aragorn, Captain Blood to King Arthur, if there were swords being swung, he was probably reading it.

Since the late 90s, his passion has been the reconstruction and preservation of armizare, a martial art developed over 600 years ago by the famed Italian master-at-arms Fiore dei Liberi, that includes the use of the two-handed sword, spear, dagger, wrestling, poleaxe and armoured combat. In the ensuing twenty years, he has become an internationally known teacher, researcher, and author on the subject, via his work with the Chicago Swordplay Guild, which he founded in 1999, and Freelance Academy Press, a publisher in the fields of martial arts, arms and armour, chivalry, historical arts and crafts.

He lives with his very tolerant family in suburban Chicago.