THE CURSE OF BLOODBONE ISLAND

THE CURSE OF BLOODBONE ISLAND, by Adrian Cole, artwork by Miguel Santos

A tale of Elak’s Atlantis

Prologue

Under the watchful eye of the Atlantean moon, the Arrow, a sleek privateer craft, was at rest at the quayside of the small port of Ulumar, far from the main sea lanes of the young Empire. Below deck, in the captain’s cabin, Artugol cursed softly, leaning over the narrow cot. Volnus was crumpled up in it, barely contained, one leg flung over its side, arms over his face. Artugol’s companion had not improved during the day, clearly worsening. The mud swamp fever was killing him. The word in Ulumar was that few survived its rigors. Artugol and Volnus were young men, barely out of their teens, with a reasonable life expectancy, provided they didn’t get carved up in a sword fight, or chewed to pieces by any one of many beasts that populated the islands of the north eastern ocean.

They’d been lucky thus far in such skirmishes, but this damned fever frightened Artugol. Volnus was in an unnatural sleep, his flesh slick with sweat. For a big man, his frame seemed to have shrunk, his muscular arms oddly pale, as if the great strength was being leached from them.

Behind Artugol the narrow door creaked open and Eskarra entered. She was young to be a captain, but her strength of will and skill with a blade had won her the position and there were few other captains among the sea rovers who could command a crew as she did, fewer still who did not respect her. She put her hand on Artugol’s shoulder, face betraying obvious concern for the man in the cot.

“No better?” For once her voice was not hard, her tone sympathetic, and it was difficult to imagine her as the fiery character who strode up and down the deck of the Arrow, metaphorically booting the crew into action.

Artugol shook his head. “Have we tried every surgeon in this poxy port?” he said testily. “If we don’t do something for him soon, I fear the worst. It’s been almost a week.”

“There’s news. Come with me. I know you don’t like to leave him, but the crew will look after him.”

He knew the Arrow was never left unattended. Its motley band of pirates, men and lasses, were hardened seamen, and this ship was their home; they carried with them every essential they needed for a life spent almost entirely on the high seas.

On deck the bright moonlight glimmered, and a cool ocean breeze drifted over the tight harbor below ragged cliffs. Onshore, Eskarra turned to Artugol. She was of slight build, her hair tied back from a face burned by the sun, and her simple shirt and trousers would have deceived many into thinking she was an easy opponent, whereas in truth she was far more dangerous. Artugol, like all the ship’s company, was also simply clad. He was several inches taller than the girl, a lean islander who’d spent most of his youth toughening himself up on the crags of his home islands. His eyes held an eagle’s stare.

Eskarra’s mood was, as usual, difficult to read under her own stern gaze. She was an independent young woman, proud of her pirate crew, and at first she had not welcomed the advances of the new Empire under its King, Elak, who desired to curtail as much privateer activity as possible. However, the promise of pardons for all and opportunities to fight for the new King – particularly against those pirate fleets still to bow to Elak – with the potential rewards, had won her over. Artugol and Volnus, servants of Elak, had become accepted members of the crew, fighting hard and well alongside it.

“There’s an old seaman who has unique knowledge of the islands,” Eskarra said. “Most think him mad, a simpleton at least. But in his more lucid moments he’s able to talk about places he’s seen, some of which are little more than legends. Usually I’d not waste my time with him.”

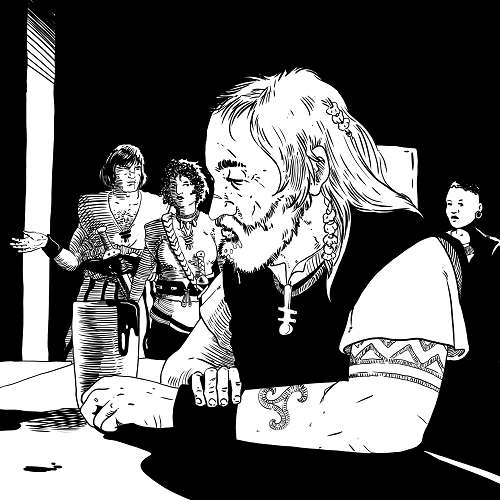

Artugol nodded, preoccupied, and followed Eskarra’s lead. They negotiated a cramped maze of side streets, entering an inn hardly bigger than a domestic dwelling. Several men and women had squeezed therein, sharing their drinks, swapping tales of their seafaring. A few eyes followed Eskarra and Artugol, relative newcomers to Ulumar, but these were enlightened times since the new King became enthroned at Epharra.

Slumped on a high stool at the end of the bar like a crumpled doll, a lone figure sipped his ale, muttering to himself. He seemed mesmerized by whatever vision he’d conjured from a memory stretching back innumerable decades, judging by his emaciated, wizened shape. Eskarra brought Artugol to him: the incredibly old man swung round, eyes ablaze as they pierced the youth, almost in fear.

“This is Varzarras,” said Eskarra, indicating the oldster. “He’s not been to sea for years.”

“No! Never again!” Varzarras hissed, shaking his head, his long, white hair moving like weed in a current. “I dare not. Too many enemies. Too many creatures of the deeps ready to suck me down.”

At another time, Artugol would have laughed. Instead he leaned close to Eskarra’s ear. “You brought me here to meet a madman?”

“We must pick the jewels from the pebbles,” she said. “Varzarras, this is Artugol, friend of the man who has fallen ill with mud swamp fever I told you about.”

Varzarras frowned, face a mass of wrinkles; his eyes lit up. “Oh, yes! Bring me more ale. It fortifies my memory.”

Eskarra went for the drinks, while Artugol sat. “What do you know of this fever?” he asked.

“Lost many seafaring friends to it. It strikes in the night like a fog, drifting in, working its foul magic.”

“Yes, I know that much,” said Artugol impatiently. “But how is it cured?”

“I was once a man of power, before the deep sea horrors discovered me and began their filthy crusade against me and my fellows.”

Eskarra returned with mugs of ale. She nudged Artugol’s arm. “Let him ramble. He’ll get there,” she whispered.

“All of my companions died of that accursed fever! However, the sorcerers cultivated a plant. The crimson orchid. A rare thing, beautiful, with a scent that no perfume could match. It grows in only one place known to man.”

Artugol brightened. “Where?”

“Hah! The gods mock us, do they not? On one island this plant grows, hidden in its jungle heart. Some tried to bring it back, to help the sick, but madness claimed them.”

“Where is this island?”

Varzarras recoiled in unfeigned horror. “Once a paradise, it has become a place of legends and sorcery, shunned by man, a tormented place where only a lunatic would set foot. A grim death awaits any who visit it. ”

“Where is it?” Eskarra echoed Artugol.

“I will tell you for a price. Bring back one flower for your stricken friend, and one for me. I had powers once. The crimson orchid will restore them! I will enjoy the fruits of youth again!”

One: The Forbidden Island

“Bloodbone Island,” said Eskarra. Around her, sitting or squatting on the narrow deck of the Arrow, her crewmen and women either gasped or exchanged uneasy glances, as if their leader had uttered an ancient curse, hinting at something better left to its private darkness. Eskarra raised a hand. “These north eastern islands abound with legends about it. There’s said to be a terrible curse laid upon it by evil gods from the far past. A grisly fate awaits anyone setting foot upon it.”

“I know of it,” said Ormullah, the huge oars master. “It’s everything it’s said to be, truly accursed. No one has ventured there in living memory, or if so, they never came back to speak of it.” He stood with folded arms, a grim statue, face clouded in a scowl that would have cracked stone.

“You know its legend?” said Eskarra.

“Said to have been raised from the deeps at the end of the cataclysm that drowned most of the original Atlantean continent, it was the home of a race of mutant sorcerers, who were equally at home undersea as on land. They used powers forbidden to them by the ocean’s darkest gods to build their citadel, not from rock and stone, but from the bones of men. In the chaotic aftermath of the cataclysm, many thousands fled the inundation, and in the waters surrounding their black island, ship after ship struck its shores. Crew after crew succumbed to its poisoned magic.” He spat into the scuppers to underline his disapproval.

Artugol was surprised at Ormullah’s revelation. It was unusual for the big man to say much, other than to bark orders, but it was clear from his mood that the place he spoke of alarmed him with its mysteries.

“The sea gods unleashed their anger on the sorcerers, furious at their abuse of power. One night they sent power of their own to bring about their downfall. There was an unearthly storm, as violent as those that had accompanied the cataclysm. The seas churned, their very beds flung apart, and on the island, stone and earth turned to boiling mud. Like the red-hot lava of a volcano, the mud poured down from the mountainous heart of the island, engulfing everything in its path to the sea, on all sides.

“At the end, the entire island and everything on it had been turned to mud. The place became as arid and treeless as a desert. All things, living or shaped from earth and stone, were changed, fused into that mud mountain. Deep into the very bowels of the earth below the island, the mud hardened, down to the sea bottom. Solidified, it locked in the sorcerers, crushing and destroying them.”

“Then it’s just a barren rock?” said Artugol.

Ormullah shook his head. “For a century it was thus. Not a single windblown seed landed there and rooted. No man dared go close. In the seas around it there was life, and who knows what frightful guardians, but it swallowed ships and crews who dared those waters. When life did begin anew, it was said to have been raised by the gods who’d destroyed the original life. From the mud rose vegetation, trees and other sprawling growths, but like nothing found elsewhere. A nightmare realm. The Nine Hells offer nothing worse.”

As Ormullah ended his bizarre description, the company murmured, no one grinning or chuckling at the oars master’s severe expression.

“I’ve heard stories about Bloodbone Island,” said Eskarra. “My mother, who was an enterprising adventurer, sailed close to it. She told me of the things that swam off its shores, and of the unnatural growths in the deeps around it. She never set foot on it, and I know of no one who has ever done so. But I also know this much – it has its treasures.”

Inevitably the pirates perked up at the word. Come hell or high water, the hint of treasure always brought a gleam to their eyes.

“Treasures worth having are always guarded,” said Eskarra. “Some by demons, and other such monsters, or sorcery, or by kings and their armies. And some,” she added, with a deliberate and challenging glare at the company, “are guarded by legends. Legends so powerful they are enough to trouble our sleep at night.

“So it is, I believe, with Bloodbone Island. I’ve no doubt it’s a dangerous, malevolent place, but who can match our steel, or ferocious resolve? You didn’t join my crew to be coddled. You are warriors.”

The implication behind her words was not lost on anyone. Now there was laughter, though nervous, and even Ormullah stared at his captain with more than a little apprehension in his gaze. Gods, did she mean to sail to the island?

“Below this deck,” Eskarra went on, “Volnus lies in the helpless throes of mud swamp fever. You all know Volnus and have fought beside him. He and Artugol came to us as novices in our trade. But they quickly showed their mettle. They’ve risked their lives for us, as we have for them. We are nothing if not a united ship. Is that so?”

Everyone was quick to agree, some raising their fists in acknowledgment.

“When one of us is in peril, we all stand with them. So – on Bloodbone Island, there is something which can heal Volnus. A unique plant that grows nowhere else. Its perfume, inhaled and taken into the body, can overpower the mud swamp sickness. It can save Volnus. Without it, he will die. And if we can harvest the plant, it’ll protect us all from that accursed illness. An even rarer treasure!” She let her words sink in and for long moments there was deep silence as the crew digested them.

“Who is with me? Who will sail to Bloodbone Island to find the crimson orchid?”

Surprisingly it was Ormullah who was first to raise a fist. “Volnus and others like him saved my life. I owe it to him. Bloodbone Island fills me with dread, but I stand with the captain.”

Zendullo, the steersman, almost as large as Ormullah, likewise pledged his support. “Turning our backs on this venture would shame us. I will go.” There were murmurs of surprise around him. He was usually the first to grumble if the Arrow was to be sent into dangerous waters.

“If anyone wants to quit the ship while we’re anchored here in Ulumar, now is the time to do it,” said Eskarra. “At first light, we sail.”

Two: Reefs of Death

When the Arrow sailed, it was with a full compliment. Terrors aside, everyone was ready to take their part, though the usual cheery atmosphere among them was subdued. As they sailed further into northeastern waters, passing the last of the populated islands, their apprehension was drawn taut as a bowstring. After several days, with a light swell on the open ocean, Bloodbone Island came into view. To Artugol’s surprise, its outline was not flat and bare, but jagged with trees and other growths. Time had finally eroded the island’s rock defenses and allowed seeds to germinate: the place seemed overgrown, as though the vegetation had run amok, smothering everything, right down the cliffs to their bases, choking fronds dipping into the sea like ropes of weed.

Zendullo, at the helm, called out in concern. “Reefs, captain! We’ll not get close this side of the island. The whole approach is riddled with reefs, and they’re packed together. They’ll rip the bottom out of the ship if we try to navigate through.” His voice was filled with barely subdued outrage at the thought. The crew knew Zendullo’s love of the ship far transcended any he might have had for his companions, and several grinned at the thought.

They had no choice but to circumnavigate the island, which was some fifteen miles in diameter, its center rising high in huge green buttresses to what once must have been an active volcanic cone. However, they returned to their starting point without earning even a glimmer of hope of breaking through the reefs. These encircled the place perfectly, too perfectly, it seemed, as though strange powers had set them there. No ship of any size dared approach the shores. The coastline offered a second problem: cliffs, rarely dropping below fifty feet, also ringed the island, their growths suggesting an impossible climb.

“How do we get ashore?” Artugol asked Eskarra. His impatience was clear to her. “I’m used to scaling cliffs, but these look more dangerous than anything I’ve seen before. Are those tendrils alive? They seem to be moving, yet there’s no breeze to speak of.”

She would not allow herself to be fired by impetuosity. “Varzarras told me there is a channel, a deep cleft in the rocks on this southern side. We can’t take the Arrow in, but a small craft can do it.”

“A handful of us?”

She nodded. “The Arrow will have to anchor outside the reefs.” She turned to some of the crew. “Prepare a rowing boat.” She called out several names and those named stood forward, three men and two women.

Artugol recognized them as among the ship’s toughest fighters. Each of them grinned, more than eager to be part of the landing party. “I’ll go,” Artugol said.

“And I’ll lead,” said Eskarra, though she grimaced as she studied the waters curling around the ship and the shadows of the nearby reefs.

“Let me go in your stead, captain” growled Ormullah, the oar master. “It’s too much of a risk.”

Eskarra ignored his concern. “There!” she said after a protracted silence. She was pointing at a large piece of driftwood, a long, broken log. It swirled and bobbed in the current; they watched it as it was slowly pulled on an erratic course to the shore, between reefs. “Varzarras said to follow the drifting logs and branches, which mark the shore-bound currents.”

Once the rowing boat was lowered, its small crew embarked, Artugol settled in the prow, watching as other chunks of maritime debris swung to and fro across the bow. He called out to the rowers and slowly they guided the craft between the first of the threatening reefs. Whatever growths comprised them, they had not formed the common coral of these waters, which was vivid in its colors. These were a sickly yellow, as if diseased, their formations oddly uniform. In places they bulged out from their main body like the bloated fingers of an undersea denizen, motionless but deadly.

The rowing boat was tossed to and fro by the whim of the currents, steered somehow between the grasp of the reefs, and the rowers prepared to use their oars to push the craft away from the reef. They knew that one error of judgement could mean the crushing of the boat’s keel, and if that happened, they would have no choice than to abandon it.

Eskarra was bent over the side, studying the waters beneath. “Strange,” she said to Artugol. “I see no fish. No weed. No sign of life.”

“Such reefs are normally teeming,” he said. “What does it mean?”

“Bloodbone Island’s curse runs far out.”

Gradually the boat bobbed and wove towards the island, its passage growing more erratic, twice almost bringing it into collision with the reefs, until a sudden wave got under it and propelled it too far to one side. The rowers rammed their oars downwards at the reef, expecting them to strike brittle coral as they worked to push away, but instead they got no purchase, slipping alarmingly, the rowers almost tumbling over the side at the unexpected lack of resistance.

“Solid!” cried one of the rowers. “Smooth as glass.”

The boat was caught by another wave and flushed towards more of the reef’s groping shapes. It struck, but like the oars, skimmed over them.

“Sand banks,” said Artugol.

“Too solid,” said Eskarra. “It’s mud. Ormullah has already warned us of the mud flow that engulfs the island. It must have come out this far. Row!” she yelled at the crew, picking up a spare oar and handing another to Artugol. Again they rowed, more frantically, and now the sea worked against them like a live thing, trying to slide them against the yellow mud banks, which in the distorted light below the water writhed and grasped at their prey, a voracious sea horror coming to life. Oars were snapped and the boat bumped more than once on the mud, but it corrected itself and the crew worked the currents, pulling away, each time more effectively until at length they came inside the ring and into placid, clear waters that offered a view of the empty bottom. This close to the island, with the cliffs rearing up like the huge green towers of a fortress, they could see the cleft that led within. Its inner walls were dark, but devoid of vegetation, as if a monstrous ax had descended, cleaving the rock in two.

Eskarra, beside Artugol, at last smiled. “The old madman was right,” she said wryly.

The tide surged and the rowers fought to keep the boat stable, but they skillfully used the movement of the waters to line the boat up, directing it into the chasm. Once past its mouth, they were in deep shadow, the cleft some fifty feet across, leading into waters that slopped and gurgled ahead, where only the faintest beams of light cut down from the heights. Apart from the soft sounds of the oars, silence prevailed. Here there were no raucous sea birds as would fill the skies on other islands. It was like entering a vast mausoleum.

Three: A Reivers’ Daughter

It had been a long, drawn-out afternoon on the Arrow. The sea was unusually calm, flat and gradually dulling to gray as the westering sun buried itself in cloud on the horizon. Zendullo, the steersman, paced up and down, checking and re-checking every rope and stay on the craft, all of which were considerably less frayed than his nerves. At the prow, the huge bulk of the oar master,Ormullah, stood, mostly as unmoving as a statue, eyes glued to the island, no more than a mile north of them. For the dozenth time, Zendullo went to the oars master and testily asked him the same question.

“Any movement?”

Ormullah shook his head and scratched at his tangled beard. “Not even a bird. Apart from that vegetation, it’s a dead rock. Cursed is right. Damn it, Zendullo, I should have forced her to let me go with them.”

“Two days, she said. Then we send the other boat in. At least they negotiated the reefs.”

“How’s the youth?”

“The same. I worry, though, that Volnus don’t eat much. Forcing a few spoonfuls of gruel into him isn’t going to keep him alive for long. Cursed fever don’t kill him, lack of food will.”

“You know he’s a King’s man. The two of them are. Elak’s High Druid, Dalan, negotiated with Eskarra to have them join our crew.”

Zendullo nodded, leaning on the rail and watching the silent isle. “Crew knows it. Resented it at first. Eskarra never liked having to deal with the King’s men. Mind, those youths have earned their place with us. They’ve risked their lives for their shipmates, king’s men notwithstanding. No one begrudges Eskarra’s determination to help Volnus. You think his being Elak’s man is why she set’s his life so high?”

“That’s part of it.”

“You know her better than the rest of us, my friend.”

Ormullah managed a rare twisted smile. “I knew her parents. Kerroch was the hardest man I met, but even he succumbed to another pirate’s blade. And Dershiva never recovered from his loss, ferocious reiver though she was. Sickness carried her off, but Kerroch’s death broke her heart. I swore to her on her death-bed that I would protect Eskarra’s life with my own, no matter what.”

“You loved Dershiva?” Zendullo was the only crewman who would dare ask.

Ormullah’s smile brightened, his eyes fixed on something that clearly lifted his spirits. His stern features uncharacteristically softened. “Of course! Which of us did not? There was never another woman like her, not that I’ve known. Apart from Eskarra. She is so like her mother. Probably even more stubborn. But she has a heart, Zendullo.”

“Kicks us and berates us, but she’d stand beside all of us. Artugol and Volnus included.”

“Yes. Artugol has a special place, I think. You must be aware of how they look at each other, how they sometimes touch, though she’s discreet. Perhaps she fears it is weakness to show desire for a man.”

“You think them lovers?”

“I think they will become so.”

“This is all about that, then?”

“Probably. But she watched her mother sicken and die. A fighting woman like that should have a better death. Eskarra has carried that with her on every voyage. Volnus is an unfortunate reminder.”

“Tomorrow,” said Zendullo. “Day earlier than agreed. You go in. If she wants to feed us to the sharks for disobeying her, let her.”

Ormullah clapped him on the arm. “It would be worth it to get her and the others out alive.”

*

The eyes of the rowing boat’s crew accustomed to the poor light. Up ahead they saw an end to the cleft, which opened out into an inner bay, an area some two hundred yards across, the water flat and seemingly tideless, lapping at a bizarre shoreline. Walls of sheer rock rose up beyond it, partially overgrown, but with open surface areas that were pocked with cave-like openings, possibly burrows, though nothing stirred within them. The shore itself was bare, its gleaming banks of mud dried hard as rock, sculpted into unnatural shapes that had all the crew gasping. It was as if a company of artisans had fashioned these, attempting to create a life-size village, with dwellings and a crude quay. Yet the work had failed to achieve its goal – this place was a mockery, a grim ruin, its buildings twisted and tormented into something grotesque and unnerving.

“The wrath of the gods fell here,” said Eskarra. “The mud flow from the upper island engulfed everything, alive or otherwise.”

Artugol studied the mud banks as the boat drew close. They looked soft and unstable, but as the oars were used to probe them, they proved to be as smooth and solid as polished marble. Even so, stepping ashore, Artugol shuddered.

Four: Night Monsters

The rounded mud flats curved in a miniature bay and rose in globular tiers to humped and twisted shapes that had the vague appearance of constructions, mangled buildings. Beyond them the jungle reared, massed greenery so profuse it had knotted and tangled itself into a seemingly impenetrable wall, almost solid. Strange flowers and fruit hung in abundant clusters and in a few places the trunks of immense trees showed through, their wood dark and gnarled, more like rock than plant. Up and up the greenery soared, ringing in the tiny bay, the uppermost branches overhanging and trailing great loops of vine and knotted vines, with ferns the size of trees burgeoning out from all sides. It would have been fabulous had it not been so sinister.

Artugol bent down and examined the floor of this amazing place. The hardened mud had set, tough as the granite cliffs he had known as an islander. “It seems hardly credible this mud must provide all the sustenance for the jungle,” he told Eskarra. “I suppose if it’s some kind of volcanic loam, that would explain it.”

She nodded, studying the sky far overhead. “The sun is dropping outside. We’ll camp. Varzarras said we’ll have to climb up near to the rim to find the flower. We’ll do that tomorrow.” She called to her reivers to fetch brushwood, anything to feed a fire, and everyone set about searching.

Two of the men found a crude pathway, where a thick finger of mud had probed the undergrowth before hardening. At its end there were low-hanging branches and the men chopped into them, cutting and trimming material. They laughed and joked as they worked, mainly to counter the eerie silence that had clamped down, but they were nervous, constantly studying their surroundings. One of them, Neyhal, mistimed a cut and his blade bounced back from a sturdy branch, nicking his forearm. A trickle of blood ran from the cut, and he licked at it, grunting with brief annoyance.

“Some hell-hole, this,” he snorted. “And us here on the words of a madman. Likely he dreamed the whole thing up.”

Beside him, Druach nodded. “Probably. Sooner we get back on the Arrow the better.”

However, they put their backs into the work, gathering a sizable bundle. Neyhal thought no more of the cut, but it continued to dribble, until several drops fell, landing on the hardened mud. By the time the two men had finished their work and carried their spoils away, Neyhal had left a small trail of blood spots. They gleamed like jewels, spreading briefly before being absorbed by the mud. When its rounded bulge shuddered, like the hide of a large animal, there was no one to see the unnatural movement.

At the camp, where larger branches had been raised and bound together to form a crude lodge, a fire had been lit, and as thick smoke rose in a curling plume, there was enough heat to warm the company, which sat around it and chewed on the sliced meat they had brought. It was salty and almost raw, but they were hungry enough to enjoy it. There were pools of cool water behind the banks of mud, clean enough to drink.

Gradually the company fell asleep. Eskarra and Artugol took the first watch, sitting a small distance apart from the lodge. Already the sky had darkened, and the smoke tendrils disappeared into it.

“You and Volnus have been friends for a long time,” said Eskarra.

Artugol nodded. “Born a few months apart in our village. We learned to crawl together. Never been separated since.”

She looked serious, but Artugol was used to that. Whatever life she had lived, it had made it difficult for her to smile often. In the short time he’d served under her, albeit as the King’s representative, she’d generally been difficult to engage in conversation. Her intention to help Volnus now had been a pleasant surprise. “We’ll save him, I promise you,” she avowed.

He sat close to her, though he was always careful not to encroach. He wanted to hold her and tell her what was in his heart, something he’d hardly dared admit to himself. Perhaps intuition had already revealed that secret, but she mostly kept a certain distance between them. He sensed she was attracted to him, but told himself it was wishful thinking. Volnus was the one who knew how to charm the women, but Artugol always found it hard to overcome a natural shyness. He disguised it with gruffness, but not everyone was fooled. Volnus, of course, teased him brutally.

“You fear for your friend,” said Eskarra, about to say more, but he turned, certain he had heard a sound beyond the rough lodge. The two of them rose swiftly, silent as cats.

In the darkness, on the trail that Neyhal and his companion had walked, the spilled blood had seeped deep down into the mud, softening it, feeding it like nutrient. In response to it, the mud had altered. A small section of it bubbled, melting, turning to something far more malleable. The power surged along the mud flat and more areas bubbled, pushing upward to create shapes that leaned and swayed upright, clumsy statues, formed by invisible, inexpert hands.

The humped structures behind the camp were bathed in the subtle glow of the campfire, adding to their alien look, and shadows seethed within hollows that could have been windows.

“This was a city,” said Eskarra. “Buried under the mud flow, along with everyone who dwelt here. Who knows how many of them are under us, entombed?”

Artugol gasped as he saw something stumble out from one of the cave-like openings in the structures. Squat, naked and hairless, it shambled forward, its head a flattened blob on shoulders without a neck. There was no face, just a few features, hollows for eyes, a vertical smear of a nose and a gash of a mouth. From this uttered a groan. The crude man-shape sniffed the two humans before it, its dark mouth opening wider, and it raised its bulbous arms and clutching fingers like fat worms.

Neyhal, who had barely managed to sleep at all, his wound of the day a nagging pain, was first to his feet, shouting at the others: instantly they were on their feet, used to coming out of a shallow slumber at sea in response to a challenge. Artugol was first to meet the oncoming creature, slicing at it with his rapier, but the blade whanged off that thick skin. To his horror he saw several more of the monsters shuffling out of the buried buildings, all reaching out hungrily for their human prey.

Five: A Taste for Blood

The reivers fought frantically as a score or more of the shambling horrors closed in, snatching clumsily at them, fortunately slow-moving, their actions not well coordinated, as if human endeavors were unfamiliar to them. Artugol tried several times to pierce their slippery, partially formed hides, but fruitlessly. He and the others were pressed back. Neyhal seemed to be the focal point of their attention, and as his own sword arm rose and fell, equally as ineffectively as Artugol’s, blood seeped anew from the wound he had given himself earlier. It had worsened, and three of the monsters crowded in on him, drawn to the scent of the blood.

“Protect Neyhal!” cried Artugol, realizing, and the reivers attempted to get between him and his attackers. However, several others also pushed forward, totally fixed on Neyhal, so that it was impossible to shield him from their groping fingers. Inevitably he was knocked to the ground and buried under a rush of bodies.

Druach, closest to him, shrieked his anger and chopped with his war ax, bringing it down in ferocious cuts on the backs of two of the attackers. It struck resoundingly, but might have smitten stone for all its lack of penetration. It did serve, however, to knock one of them aside. For a moment Neyhal struggled to rise and free himself, but one of the creatures had clamped its mouth to his bleeding arm. It came away dripping blood, and Artugol saw the wound had become a long gash, bleeding copiously. It sent the creatures into a frenzy, like sharks fighting over a bloodied victim at sea, tearing and rending.

The first of the creatures drew back; in the firelight, its entire body shone with a weird new energy. Inside it, shadows were coalescing and Artugol understood what they were. “Bones!” he gasped, pointing.

Eskarra nodded. “The blood,” she said. “Once consumed, it changes them.” She and the others drew back, watching the transformation of the creature, and then others that had fed on Neyhal’s blood. Their shapes were altering, becoming more human, although they were yet parodies, their bodies contorted, malformed. Their faces developed eyes and other features. At best they were like the work of an experimenting sculptor, incomplete and lacking the final touches that would make them less nightmarish.

Druach, horrified by the rending of Neyhal, who seemed about to be cannibalised by these monsters, rushed at the creatures and struck at them anew, but they brushed his ax aside as though it were a frond. Eskarra and Artugol both yelled at him to keep back, but so deep was his fury that he kept at them with his war ax. It was impossible to restrain him and inevitable that he would also be wounded. As soon as that happened, he was attacked by four of the stumbling horrors and they pulled him to earth, their mouths clamping on his leaking wounds.

“Withdraw!” shouted Eskarra. The remaining four did so quickly, backs to the crackling fire.

“We’ll have to take to the boat,” said Artugol.

Eskarra cursed. “If we quit the island now, we’ll never get ashore again. We stand and fight!”

“See, even more are coming,” said Dendric, the other surviving man. He bore a huge scar across one shoulder, but it did not seem to have diminished his strength. He was right. A fresh swarm of the devils had awoken, pouring from the houses and forest, their pending attack irresistible.

Artugol bent down and picked up a short branch protruding from the fire. It blazed, its sap acting like oil, and instinctively he waved it at the first of the creatures. Immediately it fell back, stubby hands raised against the heat and light. Artugol pressed forward, jabbing the flaming torch at more of them and the effect was instantaneous: they were afraid of fire. The reivers realized at once, each taking a firebrand. Quickly they formed a short wall and forced the creatures back. By now there were at least a hundred of them, most in their basic, mud-figure form, with others developing into the quasi-human shapes. All drew back, crowding the shore area.

“If we can repulse them,” said Eskarra, “we can take the path into the heights. We’ll cut fresh branches as we go and keep torches lit.”

Carefully the five of them worked their way beyond the clearing to the area between the strange buildings, the mud creatures held at bay, though only out of reach of the fire. They clearly had no intention of relinquishing the pursuit. Artugol briefly studied the twisted buildings and saw they, too, were changing, their outer layer of dried mud dissolving, running like great tongues of molten muck. The city, like its denizens, was slowly transmuting, as though all the spilled blood had released the ancient magic of the gods.

“Here’s a path!” called Brenna, one of the warrior women. She was stocky and bore as many scars as Dendric. Her fierce expression made it clear she had no intention of going back. She pointed to a passage through the leaves and thick bracken, cutting at it with her sword, glad to have work for it. The others joined her, using their torches to hold back the following creatures, Artugol thrust hard at the chest of the first and instantly it burst into flames, burning with an extraordinary intensity, scorching the vegetation on either side. Whatever was trapped inside the mud form screamed horribly in agony.

While its companions pulled back as one, unable to pass the blazing inferno, the reivers made their way up the steepening path in desperate haste, hacking aside creepers and undergrowth. Out in the forest, nothing stirred, the darkness beyond the glow of the torches starless and deathly silent. Some distance below the group, the flames burned on, but none of the mud creatures were following, constrained by the blaze. Up ahead, the low mountain’s bulk loomed, an even darker stain on the nightscape.

Six: Citadel of the Fallen

As they climbed, holding aloft their torches, the reivers studied what little they could see in the glow. Around them, the mountain was silent; sounds of pursuit quickly receded far below them. They remained on the hard mud path, twisting and turning ever upward like the winding of a huge serpent, the gradient steepening. When they had gone far enough, they paused to cut fresh branches, trimming them and strapping them to their backs, in readiness for when their torches sputtered out. If there was any life on the island other than the horribly revived mud beings, it did not show itself or otherwise indicate its existence.

Artugol followed close to Eskarra at the head of the party. He could see her face in the glow, its features pulled into a grimace of anger and sadness.

“Two men lost,” she hissed. “We must not fail in this business.”

Brenna moved forward. “They knew the risks. We always do, Eskarra. You can’t shield us all from the things we challenge,” she said.

“She’s right,” said Dendric. “We all know the risks.”

“Still it comes hard when our companions die,” Eskarra said bitterly, then fell silent. Artugol knew better than to comment, though he wanted desperately to offer her some kind of comfort. At times like this she seemed more unattainable than ever.

As they got closer to the rim of the crumbling caldera, the forest became no less matted, the vegetation spilling over the rim on both sides, a choked barrier of root and branch, vine and creeper. Dawn was seeping into the eastern clouds, its light tipping the edges of the jungle, adding a bizarre, bloody tinge to motionless leaves. The path cut down through a narrow rift, its sides flaking, the only place apparently devoid of plants. Underfoot, the hardened mud was thinning. It gave way to earth and loam, comprised of the falling leaves of the ages.

Beyond the cleft, the reivers came out into a flattened area, a small plateau, ringed by more trees and weed-choked rocks that had an unnatural geometric feel. As the company entered what appeared to be a time-worn amphitheater, the five warriors stared at their surroundings, seeing in the moss-hung rocks the recognizable shapes of statues, not of men but of disturbingly strange creatures, possibly sea dwellers, with long, snaking arms and extraordinary aquatic features. They had the look of guardians, opposing any further progress, created, possibly by denizens from below the waves, given the marine nature of their bodies, shaped like nothing previously seen by the reivers.

“Were these the gods of this place?” said Artugol softly. “The ones who vented their wrath on the sorcerers of the island?”

Eskarra nodded. “That or their servants. Varzarras said there is a central temple, the heart of the island kingdom. It is there we shall find the crimson orchid.”

The other three reivers had been searching warily among the statues, cutting at the undergrowth. Brenna called. “Here! The path goes down again, though the steps are overgrown.”

By the increasing light of dawn, they all saw the open bowl of the extinct volcano. It was filled with jungle chaos, a great green lake of verdure, fathomless, not a bare rock protruding. Life here was almost impossibly rampant, so choked and congested with vegetation that it seemed remarkable it could have survived its own furious conquest of the land. The path widened out into a series of deep steps, somehow resistant to the rabid jungle growth, yet slippery with lichen and mould. They led to the ruins of what could have been a temple.

The company clambered down to it, careful to hold on to their brands. Halfway down the dangerous stairway, Artugol turned and looked back upwards into the partial dawning light. He was appalled to see even more statues looming above, these much larger than the ones in the amphitheater. Their faces were far more horrifying, something from the worst sea nightmares imaginable. Those frightful gazes suggested the demonic, and their arms, elongated and ending in frozen, grasping suckers, reached out in a fixed threat, a promise of a bloody death.

To his horror, Artugol thought there was movement among the malevolent sculptures. Their numerous eyes were alive, picked out by the brightening dawn, the silence of the jungle broken by the cracking of rocks. Quickly the five reivers dropped down the steps and under the shadow of the first temple block. As one they looked back. Dawn had broken through and now the statues were lit up. Their heads did move! A score of them creaked as if on mighty hinges, and those hungry eyes turned skywards, watching the oncoming day.

“They are night creatures,” said Eskarra. “Varzarras said so. Their sea gods swam in utter darkness, far down in the remotest deeps of the ocean. Their movements will be very restricted by day. Dawn has not come too soon ”

It quickly became apparent that she was right, for the statues had frozen once more, faces twisted in frustrated fury, held in thrall to the sunlight. The reivers ducked under the portal and entered a temple thick with dust and shadow, though the torches threw its interior into sharp relief. Whatever had been here was broken and strewn about the rubble-strewn floor. Mounds of leaves had turned to soil, sprouting weeds and trailing ivy that had been captured by other growths hanging down in festoons from the shattered roof.

“Search every corner,” said Eskarra. “The flower should be here somewhere.”

They split up and began looking, wandering through a maze of rooms, some of which were too choked to enter, others roofless, yet more in danger of collapsing. As the morning wore on, Artugol began to feel a sense of despair. They had come here on the promise of a madman. Now, surrounded by this alien place and its ruins, its sense of death and destruction, he wondered if the flower really existed. Had Varzarras simply dreamed up his visions? Were they fact or simply legends?

Entering what had once been a larger hall, he gasped, and the truth hit him like a cold wave.

Seven: Lair of the Sorcerers

Eskarra had visited three low chambers, all lit partially by shafts of light from the disintegrating roof overhead. So far, nothing but rubble and ruin. There were mushrooms and other shadow growths, but no sign of the promised flower. This room looked as if it once had an elongated sunken bath in its centre, now choked with bricks and tiles, fused together with more fungal growths. There were a dozen or more holes in the walls, several inches across, possibly old pipes, gaping at her like surprised mouths. She was about to quit the room when she heard sounds within the pipes. Something rustled, possibly a strong draught. Perhaps the pipes fed air into the chamber when it was undamaged. Or water. A few thin vines hung from the lips of some pipes and these trembled now, gently at first, but then more violently. Something was coming.

Eskarra stepped back, sword poised. Rats? Other creatures, disturbed by the human intrusion after so many years? When a shape thrust its blunted head forward into the light, she gasped. Serpent! Yet unlike any she had seen before. At once she stepped back and gave a shout. In response, more serpents emerged from the holes, a dozen nests. These creatures were fat and twenty feet long, constrictors that could hold and crush a human body easily. Shocked, she stumbled backwards, almost falling into the sunken area. She let out a shriek which echoed along the passageways as the first of the serpents attacked her.

She used her sword effectively, timing her cut so that it bit deep into the thing’s neck, its vital juices frothing and spilling. Yet even with its head half severed, it came at her. All the frustration and furious anger at the loss of two of her companions fuelled Eskarra now, and with a second swipe she sent the serpent’s head flying into the dust. Behind her, rushing into the room, Brenna, Tormea and Dendric found themselves also confronted by the serpents, as a score of them came at them in a united attack. The reivers’ horrified reaction almost undid them as they took in the terrifying spectacle. Instinct fueled them, however, and as they backed off, they all hacked and stabbed at the weaving heads, feeling their blades cut deep and not rebounding uselessly as they had when striking the mud creatures in the fight by the shore. Yet the odds against the reivers were stacked against them.

They retreated out of the chamber with Eskarra. Tormea, the taller of the two women, slid one of the branches she had trimmed from her back and used it to drive between two of the loose stones that formed the crumbling archway around the door. Tormea’s muscular arms bulged as she gave a jerk and the stones slid outwards, followed by the immediate collapse of part of the arch. In the confusion, with dust billowing outwards, the serpents momentarily drew back. Tormea rammed her makeshift staff into more loose stones, levering them out and completing the destruction of the arch, which crashed down, bringing a huge section of roof with it. One of the serpents got through, writhing in agony as tons of stone rained down on its back half. Eskarra drove the point of her blade up into the soft flesh beneath its mouth and tore it open, spattering herself in blood.

The doorway was completely sealed. Eskarra wiped muck from her face and gave Tormea a grim smile. As the four reivers turned, they heard a shout from beyond and quickly ran in response. They came into a much wider chamber, where they saw Artugol. Beyond him, leaning over, thick with cobwebs and dust, was a large statue. It was of a human, an important figure, judging by its carefully sculpted robes and medallions, and the stone-wrought finery circling its arms. Even partly obscured, the face was recognisable.

“Varzarras!” cried Eskarra.

Artugol nodded. “One of the sorcerers, perhaps a king. He did know the secrets of this place.”

“Then we’re not on a fool’s errand,” said Brenna.

“No wonder he wants an orchid for himself,” said Eskarra. “Not so mad.”

“There’s a door behind the statue. I’ve cleared some of the rubble from it,”

said Artugol. Quickly the others joined him and soon they had shifted enough detritus to reveal the wooden door and heave it partially open. Light spilled in, enough to see there was an outside courtyard beyond, although it was richly overgrown, choked with plants hanging from high above.

“It must be here,” said Artugol as they forced the door wider.

Eskarra set Tormea to guard the exit as the rest of them got busy at once, cutting away the wall of greenery and other plants, flowers of brilliant hues and extraordinary blooms. The air was rich with the sweet smell of released perfume, clouds of motes dancing in the brilliant sunlight. Exhausted, the reivers paused. As they did so, Artugol cut aside the fronds of a rubbery bush, to reveal a small, more open glade. Around it, seemingly untouched by the rampant weeds and tendrils blanketing everything else, a dozen crimson flowers were open to the sun, drinking it in.

Eskarra stood close beside Artugol, gripping his arm. “These are what we came for. These will save Volnus.”

He put an arm around her, then realized he may have overstepped the mark. But to his amazement she turned and kissed him lightly on the lips. There was no time to react. They went to the flowers, kneeling down.

“Gods, that perfume!” he gasped. It was heady, its sweet scent powerful.

“Be careful,” she said, but she, too, caught the powerful scent. Both of them felt themselves on the point of swooning, turning to raise their hands to the others. However, they were also caught unawares by the extraordinary strength of the emissions of the flowers, dropping to their knees. In moments, all four of them were lying prone in the thick grass, victims of an unnatural sleep.

*

Ormullah growled like a bear, glaring at Bloodbone Island in frustration. “The afternoon wears on. They’ve already spent one night there. I should go.”

Zendullo nodded. “Aye, as well go now as ever. Take four with you, and watch that tidal race. You saw how Eskarra crossed over.”

The huge oars master wasted no more time, and soon the second rowing boat had been lowered. There was no shortage of volunteers for the crossing. The westering sun was low, evening imminent. On the island, the jagged cleft was a tall, black stain, its inner darkness pulsing with invisible terrors.

Eight: The Hell-Spawned Gods

No sooner had Artugol, Eskarra and the others fallen into the drugged sleep of the orchids, than they were adrift in the dreams powered by their exotic perfume, for each sleeper, a similar experience. Artugol felt himself tumbling slowly in the ether, the air around him bright, falling gradually through clouds, dropping deeper into the embrace of the sea. Strangely it grew lighter as he fell, not darker, as ocean abysses would have done. Far below, wrapped in huge fronds and trailing streamers of weed, the towers and structures of a city spread out on the seabed, and through the endless forest of weed, fantastic alien creatures drifted like colored bubbles on a breeze. Silence closed in the extraordinary vista, and the atmosphere, whatever it consisted of in this dream state, was calm and relaxing. Turning, Artugol saw the floating body of Eskarra and the other two reivers. Each of them waved languidly as they all sank slowly downward.

Several floating creatures nudged past, huge unrecognizable entities with multi-hued domes that glowed, lit from within. Shoals of oddly shaped fish flashed as they turned in the sunlight from above that was as bright as if it cut through air rather than the sea. Artugol and his companions, who had lived on and by the ocean all their lives, were well used to seeing mysterious creatures flung up in storms, sometimes dredged from far below, but the things that swam in these waters were unique to them, like visitors from another dimension. The dreaming minds understood that what they were seeing, scenes from long ago, a hundred years or more, events that had shaped their present.

Beyond the city, rising up behind it like a vast cloud, a sea-bed mountain soared, dark and featureless, its rock gnarled and pitted, in places sheer, in others a mass of apparently fused globules of cooled rock, creating an enormous natural structure that reached for the distant sky beyond the waves. Artugol understood instinctively that this was Bloodbone Island’s underwater foundation. As he and the others drifted closer to the mountain, hanging like discarded dolls over the underwater city, they sensed something else, a living presence within the mountain. Something incomprehensibly colossal. Somehow they knew what it was – one of the gods that the race of sorcerers had offended. Indeed, their sorcery had trapped it within the mountain, and they were leeching its otherworldly powers, making themselves quasi-divine, but in ways that would have appalled humanity. They had risen up on to the island and created their citadel there, and built it not from stone but from the bones of men.

Artugol felt the intense anger of the god-being trapped in the mountain, its impotent fury emanating outwards like heat from a furnace. For decades it had been imprisoned, weakened by the vampiric feasting of the sorcerers. Yet its desperation had not been ignored. From far off in the uttermost deeps of the ocean, other creatures stirred, beings unknown to Man, which had roamed the very floors of the ocean since its early formation, beings that had been spawned around a distant star, refugees from wars beyond human understanding. They had fled some world-shaking catastrophe to this world’s ocean bedrock but now they were coming, in answer to the call of their trapped fellow. Artugol’s mind veered away from contemplation of these Hell-spawned immensities, knowing it would lead to madness for him and his companions. He sensed unbelievable size, as though mountainous beings were about to emerge from the darkness. He felt Eskarra’s hand clutching at his and together they drifted mercifully further away from the city, up into the emptiness of the ocean.

Below them they knew the fate of the city was sealed. From limitless oceanic distances, the monstrous god-beings came and vented their vengeance on the sorcerers, unleashing their dreadful, cynical powers. The mountain shook, blurring as the waters around it clouded, and numerous sea creatures fell to the ocean floor, blasted apart by the horrific clash of powers. In the utter confusion, Artugol and his companions drifted through a silent darkness, wafted away from the chaos. Eventually they emerged into the light, floating once more in the ether above Bloodbone Island, although what they now saw remained in the island’s forgotten past.

Its high citadel, up on the peak and the paths that led from it down to the city at its shoreline, seethed and boiled with a molten flood, a golden mud-flow, gushing endlessly from the caldera, as if the sea bottom had risen ever upwards, transformed into this gelatinous landslide that carried all before it. Nothing below the crater rim survived the flow, down to the sea and beyond it. Underneath the waters, down the side of the mountain, dark brown runnels of mud blended with the rock, creating an illusion like dried wax spilling down the sides of a candle holder, but on an extreme scale.

In the citadel itself, high above the boiling sea, the last of the sorcerers vainly sought to hold back the powers of the beings they had abused. Locked inside their innermost chambers, they waited. For days the storms outside raged, like a new cataclysm, an upheaval almost as devastating as the previous ones. The creature they had trapped was freed at last and together with its hell-spawned rescuers, made its way back out into the vastness of the ocean and ultimately down into its fathomless abysses, where no man could venture. When the sorcerers dared to emerge from their lair, they found that guardians had been set around the rim of their citadel, monstrous demi-gods that waited for them, hungry as slavering hounds. The sorcerers could not pass that circle, and remained trapped. Their powers waned, until only one last source remained – the crimson orchids. These, brought from some other, unknown dimension, gorged on the molten mud burgeoning out from the crater, feasting on that wild sorcery. The flowers imbued the survivors with enough of this to enable a small handful to flee Bloodbone Island and out to the world beyond. It was a desperate, forlorn flight, for all of the once mighty sorcerers succumbed to madness and either died, starving on remote, barren islands, or were snared and executed by angered seamen who had lost friends and family to the abuses of the sorcerers in their pomp, and whose bones were now rotting under the mud of the island.

Only one survived—their last ruler, Varzarras, himself close to madness.

And on the island, the volcanic mud released by the angered gods sealed everything but the inner temple, and nothing could grow. Only the crimson orchids and surrounding plants lived on, but locked away, their powers impotent. Guardians were set about them, the monstrous statues, the serpents, and other, unseen horrors. Around the coast, other guardians dissuaded roving sailors or anyone foolish enough to try to land on Bloodbone Island.

All these things, this violent, terrifying history, the dreamers watched, understanding. Something shook them now, a physical presence. Artugol was the first to awaken, rough hands shaking him. He saw the anxious face of Tormea above him.

Nine: Flight from Madness

“Thank the gods!” said Tormea as the last of her companions woke from the drug-induced sleep. “I was afraid you were all lost.”

Artugol struggled to his knees. “Quickly,” he called to the others. “All of you – pull your scarves around your noses and mouths. Inhale as little of the flowers’ perfume as possible.”

As they all did so, including Tormea, Eskarra was rising and nodding. “The sorcerers,” she said, her voice almost muffled. “They gave themselves terrible powers, superhuman strength, longevity, powers of the mind.”

“The gods don’t want the crimson orchids taken from here. Their powers are too dangerous to release into our world,” said Artugol. “We must act with great caution.”

He turned to the crimson flowers, preparing to use his blade to dig a single orchid free of its soil.

“Wait!” cried Brenna. “Surely It’s too dangerous!” She looked to Eskarra, whose scowl had deepened. “After what we have seen, dare we take any of the flowers back?” Brenna went on. “What if they send us and the entire crew of the Arrow into that drugged sleep? None of us might awaken.”

Tormea and Dendric were nodding, their feelings written clearly on their faces. “Aye,” said Dendric. “Surely we cannot risk that? There’s more horror here than we could have foreseen.”

Artugol turned to Eskarra, an agonized look on his face. “But what of Volnus? Only the crimson orchid can save him.”

Eskarra’s expression was equally pained. She stared at Artugol as the others drew back in confusion, though their views now were obvious.

He leaned close to her, speaking softly. “You can’t just abandon him. There must be something. If we could take one plant, sealed in a bag. Once it has been used on Volnus, we can burn it.” His eyes stared into hers. He knew this was to be a test of any potential future relationship between them. If she refused him now, they could never be anything more than ship companions. He understood that she knew it, too.

“And Varzarras?” she said.

“Nothing for him. His life was spent in deceit. Let him pay for that.”

She nodded and whispered so that only he could hear. “Take one plant and hide it inside your shirt. If the others realize, they may try to kill you. The crew, too. Go on. I’ll shield you.” She pushed past him and pointed with her blade to the exit. “Go back,” she told Tormea and the others. “We need to get away as swiftly as we can. Night will soon be upon us and the guardians will wake.”

As one they went back into the ruins. Artugol quickly dug up a plant, muffled it in a small bag he had brought and slipped it inside his shirt where it would not be noticed. He followed Eskarra, wanting to thank her discreetly, but she ignored him, concentrating on their passage through the thickening shadows. Beyond the old temple the small company came back to the steps leading up to the crater rim. It was lit by the fading embers of late afternoon. They had been unconscious longer than they’d realized—it would soon be dark. As they climbed, several of the ancient statues loomed over them, their extended arms seeming to reach down, imbued with hungry life, eager for human blood. Somewhere inside each of them, stone ground on stone.

It was a demanding climb, the old stairway steep and broken by gnarled limbs of ivy, but the company climbed over the rim. No sooner had it done so than the reivers heard louder cracks behind them and the snapping of branches, the vibration of the ground. The statues, free of sunlight, were awake—moving. The gods of darkness, horrors deep under the ocean the dreamers had seen, had poured their energies into the stone itself. Tormea had kept one of the torches burning, now lighting others, until all five of the reivers carried a fresh firebrand. There came a unified ululation of fury behind them in the knotted trees and undergrowth, testament to the anger of the pursuing guardians.

“Light and fire!” called Eskarra, leading the company. “They abhor it. Keep the torches high.” As she spoke, something tore through the air above them, a mighty appendage, ripping at treetops and tearing them aside. However, the company sped on like rats in a run, coming again to the hardened mud trail. It gleamed in the torchlight, like the sweating hide of a great beast. Downwards they sped, almost slipping and falling. In the haste and confusion, a single torch was inadvertently dropped, sputtering on the mud.

Artugol glanced back and saw to his horror that the mud was melting. The fallen torch had ignited something in it combining with the powers of the old gods, creating a fresh slide, small but increasing in volume, and it followed them down the mountainside. He exhorted his companions and they rushed at breakneck speed, also feeling the shifting of the mud slide, reactivated again after so many years. Overhead something vast and winged swept around them like a cloud, dipping down, but deterred by the blazing torches. On either side of the trail, other huge shapes blundered through the undergrowth.

All their powers will concentrate on preventing the flower from leaving the island, thought Artugol. He held the concealed bag close to his chest, almost stumbling, but doubly determined to get away.

Somehow they got to the lower part of the path without anyone tumbling into what would surely have been their death in the knotted verdure. The mud path had widened and they had outdistanced the oncoming mud flow, at least for a while. However, their exit on to the beach was blocked off. The mud creatures they had fought earlier had not left. Some had fallen to the fire, but the remainder, scores of them now, gathered like an immense herd, and it had one unified purpose. They gazed at the fugitives from distorted human faces. Then charged.

The torches swung in blazing swathes as the reivers fought in sheer desperation, setting alight shape after shape, until a conflagration lit up the beach, its backdrop the former buildings of the city that had been its port. Already, in the earlier fire, countless blocks and towers had been freed of the no longer solidified mud, and their own dire secrets had been revealed. They had not been constructed of brick and stone, but were hewn from bone. Human bone. Countless thousands of them had been fused together, melded into the bizarre architectural nightmare, and in some places there were towers built from nothing other than human skulls.

Artugol and his companions stood shoulder to shoulder, the city and its demented defenders ablaze, the mud bubbling and boiling. On the lower shore they saw their rowing boat. It, too, was ablaze, quickly being incinerated, and with it all hope of a return to the Arrow, far out in the bay.

Ten: Fire and Bone

They got close to the shoreline, torn between making a stand and risking taking to the water. In the end they were reluctant to toss aside the firebrands, knowing they would almost certainly be unable to reignite them. They waded out, waist deep, but the transmogrified creatures pressed forward, groping blindly for them, driven by a relentless desire to smother them and undoubtedly reduce them to their own physical forms. It was how they trapped all those unfortunate enough to be wrecked on Bloodbone Island.

However, the mud around them had softened, the fires in the bone buildings and along the path of the mud slide from higher up intensifying so much that in places the mud boiled away, revealing layer upon layer of human bones, a thick carpet ringing the cove. Artugol and his companions were horrified to see so much human devastation, evidence that thousands had died here over the years. Behind the heaped bones where towers had crumbled and left yellowing mounds of skulls, pyramids of those human relics leaned into the night sky, the trees snapped and crackled, some burned, huge fiery torches, others falling. Out of the inferno slithered several huge shapes, their forms distorted by the waves of heat. Guardians of the upper temple, slaves of the sea gods, they burst through the masses of bone and skull, scattering them like spoil, and lumbered on to the beach. They swung their massive tendril-like arms like clubs, carelessly smashing scores of the mud beings aside, even though they served the same purpose. The guardians, crashing through the conflagration had inevitably set themselves ablaze, yet it made little difference to their inexorable advance.

Madness reigned, fueled by time’s corrupting process, so the function of the guardians and mud beings became perverted to the point where they blindly thrashed against each other as well as the fleeing humans, embroiled in a lunatic furore of destruction.

Eskarra said to Artugol, her head close to his ear. “The guardians are set to keep things in, as much as intruders from landing. In the dreams, that became clear. The last powers of the sorcerers must not be released.”

Artugol nodded. He knew the plant must not be allowed out into the wider world, “Once I’ve used it to help Volnus, I’ll burn it.”

She looked at him in apparent doubt, and he wondered if she would actually fight him for the flower. Had she changed her mind? Would she abandon Volnus after all?

“We’ll never swim to the ship, not through those waters,” she said. They could both hear the sea churning out in the bay, beyond the great crack – as though events on the island had disturbed it, waking other powers beneath it. The mud slide, they knew, went far out, so if it was also transforming, it would be a deadly trap; there was no way to avoid its clutches.

More of the mud creatures came forward, stumbling into the water, but the reivers yet resisted, stabbing at them with their torches, repulsing them. The first of the guardians heaved up behind them, but it was already sunk deep into the seething mud, unable to free its lower body. Abruptly a score of the mud beings swarmed over it like insects, and the fire spread as if igniting oil. Clouds of foul black smoke billowed upwards, covering the beach as the monstrous guardian toppled. Behind them others paused, only their hellish eyes visible in the choking mayhem.

“We’ll never hold them back,” said Artugol. “We have to swim.”

But as he spoke, the water beyond him burst upward, writhing shapes limned in the firelight. The undersea mud was disgorging more of the amorphous things, and like twisted sea creatures, they headed for the reivers. Artugol flung his firebrand and it struck the first of them, bursting into flame. For a short time the new assault was held back, but it would not be for long.

“Discard the flower!” said Eskarra. “It’s our only chance.”

Artugol was wracked with indecision. If he threw it away, Volnus’s life went with it, otherwise they would all die. He reached into his shirt.

A distant shout rose above the roar of the flames, across the waters.

Artugol turned, squinting into the night. Beyond the first group of aquatic mud creatures, he could just make out a long shape on the tide. A rowing boat!

“It’s Ormullah!” said Eskarra. “He’s disobeyed my orders, but for once I can’t fault him for that.”

The reivers waved their torches and at once the rowing boat knifed through the water, evading the grasping hands of the things beneath its hull, making for the shore. Artugol and the others flung the last of their burning torches at the mud things, driving the assault back. The men in the rowing boat fought off all attempts to overturn it, racing forward. It swung round and at once Eskarra was pulled aboard, followed by the others.

“No time for explanations,” said Eskarra. “Just get us away from this hellish island.”

Ormullah laughed, but he studied the shore and the massed creatures, many of which had melted into the layers of bone that carpeted everything. Of the huge guardians there was no sign, but up in the skies, deep-throated sounds hinted at some aerial threat, smothered as yet in the clouds rising from the boiling waters. It was a tortuous row back through the cleft and out into the bay, but the underwater attacks subsided. At last the boat reached the Arrow, everyone dragged aboard, exhausted.

Artugol wasted no time in rushing down into the cabin where Volnus lay, close to the point of death, for the swamp fever had not relented. Eskarra stood behind him as he took out the small bag and revealed the crimson orchid. He let its perfume waft under Volnus’s nose so that the fumes were drawn in by his slow breathing.

When it was done, Eskarra handed him several jewels and colored stones that might have been valuable, “Enough to sink the bag,” she said. “Perhaps the gods of the island will accept them as recompense. Better to let it lie on the sea bed, far from shore.”

Epilogue

As the Arrow sped further from the smoking Bloodbone Island, Artugol discreetly dropped the weighted bag containing the flower over the ship’s rail. He and Eskarra watched it disappear into the darkness of the depths. Overhead, where thick clouds churned, lowering like the balled fists of the gods, the sounds of aerial creatures broke through, calling like gulls. Something had followed the ship from the island. As the Arrow moved further away from where Artugol had disposed of the bagged flower, the pursuers descended from above, their shapes indistinct in the gathering sea mist, though one of them plunged into the waves and was lost to sight beneath them.

“It seems the orchid is destined to return to the island,” said Eskarra.

“Yes, though its work for us is done. Volnus is recovering.”

“You’re angry with me,” she said. “You know, in the end, I would have abandoned him. I had to think of my crew. I could not risk sacrificing them. As captain, it was a decision I had to face.”

“You have responsibilities. Sometimes they overrule personal matters.”

If she had more to say, there was no time, for the lookout called from the mast. Before long another ship was seen on the horizon, likely drawn to these waters by the huge pall of smoke rising from the island. By the markings on its wide sail, it was a ship of the King of Atlantis.

*

Emmaneus, primary Druid of Dalan, High Druid of the King, watched Volnus as the youth ate, propped up in his cot, eyes alert, strength visibly coursing back into what had become a wasting body. “You seem in good health, Volnus. Are you well enough to board my ship?” Emmaneus had a brusque manner, openly impatient to get on with his business.

Volnus reached out for the meat slices on the adjacent table. Chewing one hungrily, he nodded. “Yes. I need to wash the stink of the last week off me.”

“You’re fortunate. Few survive mud swamp fever. You have the constitution of a bull.”

“Dying from the fever would be an ignominious way to pass.”

“I want to set sail for Epharra before the end of the day.”

Behind the druid, in the door to the narrow cabin, Artugol and Eskarra watched the exchange, both relieved to see Volnus’ evident recovery. They withdrew quietly and went up to the deck, into the early morning light. Alongside the Arrow, the sleek vessel of the King had been tied up. Uniformed sailors went about their daily chores on its deck.

“Emmaneus is Dalan’s right hand,” said Artugol. “Volnus and I are being recalled. We’re to sail with Emmaneus to the capital. Apparently the King wants to meet us and thank us for the various missions we’ve undertaken for him.”

“Then what?”

“More, no doubt. The new empire is young. The King has many enemies.”

Eskarra nodded, gazing out at the sea. Bloodbone Island was far below the north eastern horizon, not even a smudge of cloud to mark it. “Our days together have been chaotic, but interesting,” she said.

Interesting? Is that how you’d describe them? “Yes. In truth, I’d rather they did not end.”

She shrugged. “You’re obliged to go. I have my ship and crew. My priorities lie with them.”

“Perhaps you’ll be commissioned to carry Volnus and me again.”

“The King sets his own priorities. They may clash with mine.”

“And mine?”

“You’ve no choice. You’re the King’s man. He commands, you serve. You must arrange your life around that.”

Emmaneus emerged from below deck, easing cramped limbs, his gray robe stretching over his portly shape. “I won’t ask you for details of how you brought about his recovery.” He studied Artugol and Eskarra for a moment, as though he knew what had occurred on the island. “There are places in these seas that are off limits. Better not to visit them.”

Eskarra nodded. “My ship will always be at your service. We acknowledge the King as our ruler.” She managed to make her smile convincing.

Emmaneus allowed himself a brief smile. “Good. He did marry a pirate lass, you know. And all of Atlantis regards it as a fine match.” He turned and called out orders to his sailors, and they made ready to part company with the Arrow.

________________________________________

Adrian Cole has written a number of new Elak of Atlantis adventures, as well as other stories set in Elak’s world and time (including The Curse of Bloodbone Island, set in this volume). He is also the author of the Voidal Saga, now enjoying something of a revival, and is currently preparing the final 2 volumes of the Romano/Celtic trilogy, WAR ON ROME, for publication, an alternative history of the conflict between the Germanic warlord, Arminius, and Germanicus (due Sept 2023) the ambitious Roman commander at a time when the Empire sits at a crossroads in the development of Europe in a world whose history veers away from our own. Cole is also working on the final chapters of a new DREAM LORDS novel, a sequel to the original series first published in the 1970s, set 100 years after the finale of that trilogy. 2024 will see Cole’s 50th year of publication and in July he celebrates his 75th birthday: a special collection of new short fiction is currently in the works to mark this auspicious occasion!

Miguel Santos is a freelance illustrator and maker of Comics living in Portugal. His artwork has appeared in numerous issues of Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, as well as in the Heroic Fantasy Quarterly Best-of Volume 2. More of his work can be seen at his online portfolio and his instagram.