DRAGON TEARS (PART 1)

DRAGON TEARS, by Caleb Williams, pending artwork by Simon Walpole

An elbow struck my side and woke me from an alchemical slumber. My limbs were bound to the mast of some ragged naval vessel.

A boy held tight to the rigging. “Sorry. Captain orders.”

Across the sea, royal ships from Alma’Riha shot fireworks across the harbor, their golden and scarlet sails standing straight like swords. Drumming and shouting carried across the sea.

“Yadira,” I groaned.

“The princess?” the boy said. “It’s true then?”

A breeze whipped up and I suddenly became aware of my nakedness, stripped to just my undergarments.

“Is it true?” the boy asked again. “You and the princess. The two of you…”

“Yes, boy,” I said. “Many times.”

“Why wouldn’t His Majesty just kill you?”

“Exile is just death by another name. The hanged man dies once. To live alone, with only the remembrance of what was, is to die every day.”

The drumming came to a sudden halt. Though, I could not see Yadira, I knew by the trumpet blasts she belonged to Augustin now, the young princeling and future king of Alma’Riha. His gigantic flagship lumbered out of the bay and carried off the woman I loved.

“Alright,” the captain shouted from the helm. “Lift anchor, carry on!”

The sailors hurried about their tasks. The boy climbed down and helped pour a barrel of wine into the ocean, while the crew prayed that Goddess might grant them safe passage.

We sailed due east toward the setting sun and even after the harbor was long out of sight, reveries echoed beneath the twilight. Both moons staked their claim to the night sky.

The boy returned to my side with some trinket in hand. “Here. The princesses’ handmaiden told me to give it to you when we were well gone.”

“Well, I can’t grab hold of it can I?” I didn’t hide my annoyance.

The boy brushed backed my thick, brown coils and draped a necklace around my shoulders. It was a piece fit for a princess; lapis stones nested in golden lace that covered me like a gorget. A memento to remember her by. I needed nothing to remind me of her. I wept through the night.

#

The waters east of the archipelago were feared for their treachery toward sailors and each day brought fresh torment.

The sun flared such that hives broke out on my neck. Rain came and went through the night. By dawn, the rain turned to hail that pelted the ship and bruised my thighs. The men sought shelter in the lower decks, but Goddess made the sea churn and sent the ship swirling. Come morn, She held her breath and bottled up the wind. The sky cleared but we found no reprieve.

“Pirates!” A ragged voice shouted from the crow’s nest.

Their vessels were small and fast and numbered four in all. They were an audacious bunch, thinking they could plunder a Varushe warship.

One of the small boats flanked us and the mangy men aboard fired crossbow bolts, slings, and improvised ammunition over the deck. Shrapnel flew right by me. Defenseless as I was, all I could do was shut my eyes and scream. The captain gave the order to fire, and the broadsides erupted. Chain-shot tore through the sails and rigging of the tiny pirate ship, and the men aboard abandoned the vessel.

The remaining ships closed on us, cast rope ladders over the deck, and boarded us. Beneath me, a battle ensued. Thirty or so pirates and as many seasoned sailors clattered spears and swords. I shouted from the mast that I would be more useful down there than tied up, but the choir of battle drowned me out.

The fighting was violent but brief, for the sailors’ discipline quickly overcame the pirates’ bravado. Pillows of smoke erupted from flintlocks, and I curled up and prayed not to be the victim of a stray bullet. They cut down the pirates to the last man and in the end their own casualties numbered only a few.

The noonday warmth baked streaks of salt along my body, while the sailors stripped the dead of their weapons, clothes, and meager possessions and cast the bodies overboard. Come nightfall, the sea calmed. The boy climbed up the mast with hardtack and mead to feed to me. I say boy, though having seen him kill two men just hours earlier he seemed somehow older now. As he fed me, he gazed upon the symbols carved into my flesh.

“You were a scribe weren’t you?” The boy said. “Was that your profession?”

“Profession?” I coughed up crumbs. “I’m not some petty craftsmen. I’m Larohd du Masiim, a royal scribe of Varushe learned in the ways of calligraphy from my youth. All of creation is my canvas.”

“So, you are a scribe!” Without touching he traced the glyphs on my chest. “What do they say?”

“It isn’t that simple. This is divine language. That with which Goddess spoke the world into being.”

“So how do you speak it?”

“You don’t.” I leaned toward him. “I can show better than I can tell. Take that knife on your waist and cut me. Just across the chest. I’ll show you what a scribe can do.”

He looked around to see if any were watching. The ship was sound asleep. He quietly drew his blade.

“You don’t know when to quit?” A familiar ragged voice came from the lookout high above me, a crippled man who was tied up by the rigging and kept watch day and night. “A wise man knows when to let go.”

“You mean give up,” I shouted. “Abandon the deepest dream of my heart.”

“Life is loss. And in the end we lose that too.”

“So why live at all?”

“For my children and my children’s children.”

If my mouth wasn’t so dry, I would have spat. I looked at the boy and asked again. “Well, do you want to see what a scribe can do?”

The boy’s eyes glinted with excitement but after playing with the hilt of his knife he sheathed it and turned away. “Perhaps another time.”

#

I learned and forgot the name of every man aboard the ship, except the boy, Benny, and the crippled lookout who was Willum. They all remembered my name and they reveled in saying it. I supposed they didn’t often break bread with the sons of high lords.

They enjoyed my frivolous tales of court and when time allowed, they gathered around to listen to my stories about the feckless lives of nobility. They shared their own stories, personal and painful. In such a way I was initiated into their brotherhood. After a time, they asked about my markings and the ways of calligraphy.

“Goddess is infinite,” I said. “Man is finite. We toil to produce little. She wills and it is so. We speak with words, She speaks with a thought. If we could but speak as she does, what wonders could we work? Scribes spend our lives in pursuit of this knowledge.”

“Scribes command earth and sea.” Benny said with childish glee.

“A master scribe can do many things. But there is a cost for such power. A blood cost. Most scribes do not live to see thirty summers. Those that do see it through blind eyes, dumb and senseless.”

Their curiosity waned.

“Storm coming!” Willum hollered.

A mass of clouds in the north glommed together into a gray behemoth and seemed to pursue us across the sky. The crew hurried to their posts.

“Come tomorrow evening, we ought to be at Shirat, where the exiles go,” Benny said. “We’ll cut you loose and toss you over and wait till you swim ashore. That’ll be it.”

“Sem Uhm Waya,” I said.

So be it. It was a simple prayer of acceptance, spoken in the old Varushe, that archaic language which I knew little of. Though few words, at least, I had memorized long ago.

#

For two days entire the rain did not cease. The deluge was so heavy one could have mistaken day for night. The captain ordered the men to hunker down. Fear overcame the crew. In the thunder, they heard the roars of dragons. In the strange shapes of cloud illumined by lightning they imagined winged phantasms. The ship listed this way and that as seawater spilled over the rails and dragged a man down into the abyss. At last, the captain had me cut loose.

“Save us boy,” he shouted. “Use your blood magic or whatever.”

“Give me a knife.” I struggled to stand.

Benny gave me his and I slashed across my palm. I stood at the front of the boat and after a few contemplative breaths I churned my arms in rhythm with the swirling waves. I moved with the sea, and the ship turned. A force pushed against me. I pushed back, to break the waves in front of us, but the force was too great.

On the horizon, I noticed a rocky outcrop that had no business being so far out at sea. With gentle but insistent motions I compelled the waters to move aside so our ship might pass. I pushed and pulled, but my every action was thwarted by another. Waterspouts appeared from nowhere. Such conjury was a scribe’s doing, I knew, but I had never known such power could be wielded by man.

I desperately tried to steer the boat away from the spouts, but the sea whipped into a maelstrom. The ship swirled around the maw of the whirlpool and the ship ripped apart plank at a time. I soon succumbed to blood loss and exhaustion.

“Abandon ship,” the captain ordered.

We obeyed. Water rushed into the ship until at last the sea dragged it down stern first. Willum did not struggle as the sea swallowed him, but Benny tried with all his might to save him. Foolish boy could barely swim. I grabbed hold of his leg. He kicked and struggled, but I dragged us both out of the whirlpool. The dying gargles of the other men haunt me to this day.

Salt stung my open wound, but as I kicked away from the wreckage the current became more manageable, almost agreeable. The outcrop was not so far. Something gigantic slithered around it. Now I was seeing things. Despite the spasms, I carried on.

I neared the mouth of the outcrop. Suddenly, the sea inhaled and dragged Benny and me under. The current smashed us against rocks and I lost hold of him. I landed with a thud and inhaled. To my surprise I drew air. I found myself in some underwater cove.

I pulled myself ashore and stood on wobbly feet. Stalactites streaked with quartz emanated a faint glow that made it possible to see. A scream echoed from the depths of the cove.

“Benny,” I reached for a knife I did not have.

A formless shadow appeared along the far wall of the cave. It growled. I did not flinch. Its presence felt familiar. Wind whooshed by and the shadows disgorged Benny’s body. The bruises around his neck suggested strangulation.

“I smell no fear on you.” The shadows spoke in a feminine tone. “Have you no regard for death?”

“Death is solace to the damned,” I said.

“An exile. What was your sin?”

“Desire.”

The shadows solidified into the shape of a slender woman with skin like birch. Her eyes were green and endless and seemed to hide knowledge of things that should not be known.

“It was you I felt.” Blood dripped from her forefinger. She wore tatters that revealed the indecipherable glyphs on her skin. “Seems we are kindred spirits.”

“You’re a scribe.” I said the obvious.

“I was. Chief scribe to Olheric the Conqueror.”

“Amarantha?” I didn’t believe it even as a spoke it. “Mother of scribes? Author of autumn? Tamer of tempests?”

“Author of autumn? I had not heard that one before. What else do you know of me?”

“You were the first to practice calligraphy. With you at his side, Oleric tamed the great continent. You guided his ships commanding sea and sky, and he conquered every island in the archipelago. By the end of his life, he was lord over all creation. So, the poets say.”

“…and what do they say became of Amarantha?”

“Many things.” I answered coyly.

“Do they speak of how she was banished because her ways were too arcane? How Olheric’s sons cast her from their palaces to be orphaned to time?” Her grin revealed more teeth than her mouth should have been able to contain. “I wonder what Alma has woven into the tapestry of time for you, boy.”

I recoiled at hearing Goddess’ sacred name spoken so casually.

“You’re a lord’s son.” She went on. “I can tell by your comportment. Now an exile. A great fall. What possessed you?”

I didn’t answer, but I remembered Yadira’s gift and miraculously it was still around my neck. I caressed each jewel as I thought of her.

“Love. Of course.” Amarantha glared at me. “Your will is strong. Your understanding is pitiful.”

“From boyhood I have been instructed in the sacred sciences.” Some lingering sense of fealty made me defend my upbringing. “By whip and rod, I memorized all that I was taught.”

“A devout pupil to foolish masters.”

“You know better?”

“Do I?”

We both knew the answer. All the scribes in my home of Varushe, nay, in all the known world, did not make her equal.

“Teach me,” I said.

She drew uncomfortably close. “Any whom I would teach must first have fire in their heart.”

“Fire? For what?”

“Anything, but nothing besides. What do you most desire?”

Yadira. Her name rested heavy upon lips, more precious to me than even Goddess’ sacred name. I could not bear to speak it. Even thinking of her conjured a yearning within me, a burning ache that only the sight of her could quench.

“A pair of moon stones,” she said. “Resin of solamber. The bile sac from a hermit nautilus. A hanowha scale. Ogre tusk powder. A dozen ripe plematines. A beautiful lie. And a piece of your own heart. Return to me with these things before summer arrives. Then, I might teach you.”

“Ogres? Hanowha scales?” I swallowed my laughter. “Such things do not exist.”

“Then I guess you won’t find them.” She gathered Benny’s body in her spindly arms.

“…If I should find these things, where then will I find you?”

“If Alma has woven our fates together in the great tapestry, we will find one another.”

There were many questions I would have asked and others I would not have dared, but before I could say anything she vanished. I recall only the wind that lifted me off my feet, the freezing torrent that flushed me from the cove, and the darkness thereafter.

#

Light poured in through a crooked window in a small room in some rickety home. I ached and shivered. My body had been wrapped in tight bindings. Through the window, a fishing village connected by a crisscrossing network of rotten wood bridges was waking up.

“Beautiful she is,” a gritty but not unkind voice said.

A brown-skinned old man crouched at my bedside. His hair was thin and gray and most of it was in his beard. He had enough teeth to chew with. I guessed his eyes were brown behind the cataracts.

“What is this place?” I asked.

“Beggar’s Bay,” he said.

“How did I get here?”

“By Goddess’ grace. I was fishing a long way from here. Saw something shimmering in the sea. Pulled it in and you with it.” He jangled Yadira’s necklace.

I snatched it from him. “How long have I been here?”

“This morn makes eight. You’ve been fading in an out. Babbling in your sleep about ogres and such. You ain’t crazy are you?”

“Who are you?”

“I’m the fella who saved your life. Let you in his home. Whose wife has been tending to. Who are you, lad?”

“I was Larohd du Masiim, only son of Ghert du Masiim, Merchant-General of Varushe. I was a scribe’s apprentice. Sworn guardian to princess Yadira who will someday be queen of Alma’Riha. Now I am no one.”

“Well, everyone is no one here. You’ll fit right in.”

#

The old man, Ambroise, and his wife, Chandra, gave me a home, food, and an ill-fitting robe she had knitted from mismatch fabrics.

Situated on the great continent’s southern shore east of Alma’Riha and separated by mountains with the many island kingdoms in the archipelago scattered in the southern sea beneath, Beggar’s Bay was a great port city.

My days laboring at the dock for whoever would have me left my hands bloodied and blistered. I led a common man’s life with a nobleman’s resolve. A shameful sight.

People clogged the harbor. An economy of whispers thrived in Beggar’s Bay, so by night I skulked through the streets stealing secrets from the lips of strangers.

One eve, I holed up in the corner of some drinkery nursing a glass of sour swill. A mangy red-haired sailor reveled the patrons with stories of prince Augustin’s royal retinue.

“A dozen frigates at least.” He picked breadcrumbs out of his beard. “Barques. Cutters. Ketches. Schooners. A hundred or more.”

It was an ostentatious display that Augustin was lavishing upon his betrothed. They had been sailing around the continent for weeks and would for many more soliciting gifts and pledges from the lesser states sworn to Alma’Riha.

“The princess.” I muttered. “Is she as beautiful as they say?”

“Aye.” He grew suddenly sober and solemn. “Like the first flowers of springtide.”

“…I see.”

“No you didn’t. I did. She was a vision.” He smiled a gnarled smile. “Hell, she was the second prettiest lady I ever seen.”

The whole room laughed at his harmless, intolerable jest. I finished my drink, sighed deeply, and smashed him in the face. A gash opened above his eye that would heal into a scar which itself might make for a good story someday.

Eight or eighteen men surrounded me. Blows came from everywhere. Some I evaded, some I did not. A thick pair arms wrenched mine behind my back. Broken glass sliced my side. I reared back, and headbutted somebody.

Two men charged me. I focused my drunken eyes and inhaled deep. Heat rose in my stomach, singed my throat, and escaped my lips. A fireball ignited in front of my face. Tendrils of flame latched to anything that would burn. The explosion forced me backward into bodies which broke my fall.

Fire burned through my cloak. I patted the flames, leapt to my feet, and sloppily dispatched two more men. A knee to the throat. A broken arm. A dozen men encircled me. I felt light-headed. Once more I inhaled and asked Goddess to summon through me an inferno large enough to consume the place. I expelled the air from my mouth but only produced a hot belch.

My vision blurred. Twelve men became thirty. I lunged at one. They all lunged at me.

#

Chandra peeled a poultice of eucalyptus and peppermint from my chest and stitched my wounds. I winced as she dabbed my cuts with water. She smiled an apology. Ambroise walked in as she walked out. They kissed as he brushed strands of gray from her forehead.

He knelt beside me and prodded at my wounds. “My wife spent days sewing clothes for you. And you go and burn it to hell. If I had my way, you’d walk around naked. Course I never get my way.”

He chuckled as only a contended man could. I sat up and handed him the necklace Yadira had given to me.

“What for?” he asked.

“Surety,” I said. “Until we return from our voyage?

“What voyage?”

“Ogre tusk powder, hanowha scale, moon stones, a beautiful lie-”

“Goddess help me. The boy’s babbling again.”

“You’re right. It’s probably nonsense.” I grabbed hold of his cloak. “I dream mayhap. But I cannot let it go. If it means I can see her again.”

“…Yadira, you mean. The woman you kept mumbling about.”

“A wisewoman told me if I bring her all that she asked of me before summer she would teach me all she knew. With such power all the armies of Alma’Riha could not keep me from my beloved.”

“I was young once. Had a heart full of dreams. I leased my life to this lord and that. Traversed the known world. I’ve seen many things. Even dragons. I swear it. I had a wife before Chandra. Four sons to carry my name. Time took each one. Fever. Famine. War. Consumption. The loss of cherished things tempers the soul.”

“Not mine. Not until I hold her again.”

He regarded me for a long while and his expression morphed from curiosity to concern before he made his decision. “There is one dream yet, but not my own. Chandra tells me often about having a villa on the western slopes where the storms can’t reach. Trees for fruit. Chickens for eggs. Sheep for flesh. Lilacs and snapdragons just because. With a view so she can see the sun every morn and every eve.”

“Sounds costly.”

“Aye.” Ambroise snatched the necklace from me. “And I mean to have you pay for it.”

*

I used my calligraphy to perform magic acts at the dock morn, noon, and eve, and soon became a man of modest wealth.

I met a merchant who knew a smuggler who knew a thief who knew a palace priestess who prized mammon more than virtue and wearied of her post in the royal library guarding old scrolls.

I told the merchant my name was Larohd du Masiim and that I needed the oldest maps he could find and that I would pay his price no matter how much. He said my name didn’t matter and that he could not make assurances but if he could find what I asked his markup would be forty percent.

We got along fine.

I contracted his services for stationery, weapons, food, and provisions enough to make the endless repairs to Ambroise’s ship which was a modest schooner that a crew of a half dozen men could handle easily enough. By the end of our business, the merchant became a man of my modest wealth.

At our last transaction he gifted me a trinket free of charge for my loyal patronage. It was a beautiful backsword with a jeweled hilt and curved blade that rested in a leather scabbard along the length of which were written glyphs in gold leaf that matched the ones carved into my forearm. He couldn’t have known that he a returned to me my own sword and I didn’t ask how he stumbled upon it.

By summer’s end we were ready to sail.

The night before we departed, I eavesdropped on Ambroise and Chandra in the living room. He draped Yadira’s necklace around her and made no promise he’d return but said that if she did see him again, she would have her villa with trees and chickens and sunsets.

He told her, though, if she did not see him again that the necklace was a cherished possession of the princess of Alma’Riha and that she should return it to her for such a kindness would be repaid a hundredfold.

Morning arrived in her summer best, a blue sky streaked with oranges and pinks and a tease of cloud.

“Beautiful skies are ill omens,” Ambroise said. “For Goddess often weaves serenity with one hand and sorrow with the other.”

“Time will tell,” I said.

“It always does. When you’ve lived as long as I have you see the patterns Goddess has woven in your life. All is foretold. There are no coincidences.”

I wasn’t sure I believed all what Ambroise said, but as I gripped the familiar handle of my saber I could not deny it either. Time would tell.

We debarked beneath a swift sky. By noontide, the sun was beaming, and Beggar’s Bay was far behind us. Both moons were high, one full and gray, the other waning and white.

“Where to?” Ambroise asked.

“If one wishes to find something that doesn’t exist,” I said, “Which direction should he sail?”

“If you don’t know where you’re going you can’t get lost, lad.”

“East it is.”

*

It was rough sailing against the prevailing winds east of the continent. At times, it seemed we were making no progress at all. After forty days tacking and heeling through choppy waters, we found ourselves in uncharted sea. Most of the maps marked it as the end of creation after which ships plummeted into the netherworld. The more ancient parchments noted a solitary island in these reaches though they could not agree on its location. I thought it was all a conspiracy of cartographers. Whether it existed or not they all agreed on its name. Hanowha. According to the faded drawings on those old parchments, it was there that I would find my quarry, a turtle-like creature with glittering scales hard as diamond.

“Do you really think it exists,” Ambroise said to me.

“No,” I answered. “But a month ago I didn’t believe in the kindness of strangers.”

“That was the kindness of a barren woman and an old man who outlived his sons. That isn’t so rare a thing. Now let’s find this island.”

I trained my spyglass south by southeast and a knob of land appeared on the horizon. “Well, we found something.”

As we sailed nearer, the speck grew into a lush island with a misshapen mountain in the middle. Ambroise dropped anchor.

“A bit closer maybe,” I half-joked.

“I could.” He squatted on a crate. “But this way if anything goes awry, I can get out quick. Anyhow, you look a strong swimmer.”

He was nothing if not sincere. I undressed to my knickers and rolled the cuffs up above my knees. With my saber on my waist and a knife between my teeth I dove in. I paddled ashore and shook the cold off. There was no sign man had ever set foot on that place.

I took a few steps. Sand shifted beneath me. Something hissed. I brandished my blade and whirled around. A giant slug stood up on its hind legs flashing a maw of serrated teeth. I froze, from terror I admit, of a creature the likes of which I’d never imagined existed.

It hissed again and reared back to strike. A four-winged reptile swooped by and dug its talons into the worm. It darted into a thicket of overgrowth, only to be ambushed by a swarm of giant stinging cicadas. I fell to my knees and praised Goddess that I had only come to find a turtle.

Fantastical fauna covered the island—limbless flying vermin, howling feline chimeras, slithering growling abominations. Each was predator and prey to everything else.

The vines were too thick to cut even with my saber, so I crawled and climbed through the forest. The eyes of many many-eyed monstrosities stalked me. All wild beasts know to fear fire, so I had the idea to start one. I stabbed myself in the palm. The perfume of fresh blood drew my stalkers from their hiding places. The flames sent them scurrying back.

I burned a path through the bramble. Everything seemed slightly askew, such that I couldn’t quite manage to walk in a straight line. Day turned into dusk. I scoured every crevice of the island and glimpsed all manner of beasts, but nothing one might mistake for a turtle.

I stumbled upon a clearing and rested against a rotten log. A colorful toad that I knew better than to touch squatted there too. With one eye it looked at me, with another it scanned for predators, and the third it kept fixed on the sunset.

The creature began to croak. Its brethren joined in. The commotion rattled my brain. I threw a pebble at the thing. It leapt out of sight. The island quivered. An army of toads emerged from the bushes and into the mountainside. The island tremored again. Growls and chirps echoed from the depths of the forest. I jumped to my feet. The world began to shift. A stampede ensued. Every living thing on that island ran toward high ground. The sky tilted. I lost my footing. Less nimble creatures clawed desperately at the earth. Water rose around my ankles. In an instant, the whole world turned upside-down. I tumbled headlong into the sea.

A humongous shadow loomed over me. I fought against the current to turn myself upright and saw an impossible thing. A leviathan of a creature. Hanowha. Shimmering scales plated its underbelly.

It paddled over to a reef, rammed its massive head into the coral, and feasted on whatever it trapped in its bite. I stabbed at the scales, but only managed to mangle my knife. Desperate for a breath, a swam up into the large crevices under its shell where pockets of air were trapped.

I noticed a crust of grime covered its eyes. It was half-blind and seemed to react to color and light. I gasped for air while I thought up a plan. A seamount carpeted in dull grasses and dead corals rested in the distance beyond notice of the beast.

When Yadira and I were young, I’d often pick wilted stems from the palace gardens, and with a prick of blood I’d turn the petals pink and purple then pink again. A mere trick of light, but nothing delighted her more than when I’d make the jewels in her gown glow.

I swam to the mount and nestled among the corals. I swayed and agitated the debris. Lifeless coral glittered violet and green. The fluorescent glow caught the beast’s eye. It swam near with remarkable swiftness, and I quickly realized I was between a living island careening headlong into a mountain.

I kicked away from the seamount and swam toward the surface. My leg seized up and I started to sink. I did not see the beast crash into the mountain, but I felt the wall of water collide into my back and I heard the explosion which numbed my ears. The force knocked the breath out of me. I reached out for anything and grabbed something jagged and shiny. My ears popped as I floated to the surface. For a moment, darkness held me in its jaws, and I feared it would swallow me whole. At last, air filled my lungs. I buoyed in endless night. A bright light grew brighter.

“Goddess be good,” I recognized Ambroise’s snarl. “I thought you were dead lad.”

“I might be before long.” I gasped.

“What’s that?” he pointed.

I examined the thing that had saved my life, a giant scale, or a part of one at least. Its shape was unwieldy but broad enough to shield a giant. Ambroise dragged me aboard along with my prize. I wriggled around the deck in pain.

“Where to now?” Ambroise massaged my cramped knee.

“To sleep.” I said. “To sleep.”

#

It was easier sailing with the wind. After two weeks we found the eastern coast and tacked northward. I was not inclined to imperil my life again so soon, so I suggested we find a shopkeeper and procure a bottle of solamber resin. Ambroise told me that most of the solamber resin used in oils and fragrances was only an imitation that peddlers pawned off to rich travelers.

He steered into the mouth of a half-frozen river. The cold rattled my bones as the river snaked westward. We followed its path for many days.

On the fifth morn, we found an inland harbor along either side of which were thriving villages. Ambroise docked and made idle chatter with the menfolk in a dialect that I mostly understood.

“Someone must know where to find this stuff,” I said impatiently.

“Everyone knows, lad.” Ambroise said. “It just ain’t for sale.”

“Everything has a price.”

“Indeed, but are you willing to pay it?”

“Just speak plainly.”

He gleefully ignored me. We stumbled upon a caravan of drifters who were departing into the southern country toward the valley of Niashuqe where Ambroise insisted we should go. I offered to pay our fare, but Ambroise said that barter was their way. I promised to pay them abundantly in solamber resin once I got it. They laughed at my apparent jest and accepted it as fair trade for a free ride.

We hitched to their convoy, forty wagons and twice as many people. Theirs was a nocturnal tribe. By night we rode along the great southern road beneath the light of both moons. Come dawn, we set up camp and started cookfires. Ambroise seemed right at home among these vagabonds.

After breakfast, a giant approached me. Herryck (I learned his name after) stood tall as two men with six fingers on one hand and seven on the other. It had rained during the night, so his steps left great big tracks in the ground. He had hair like hay that draped his gigantic shoulders, and his eyes could never agree upon which direction to look. He set his elbow upon a stump between us and grunted.

“A challenge of virility,” Ambroise said from his tent nearby while taking a knife to his beard.

The whole camp watched us. If there was anything I enjoyed more than a challenge, it was attention. I dug a knife into my shoulder and grimaced. There were oohs and aahs, for they were not familiar with the ways of calligraphy. Blood dripped onto the stump. I tensed my muscles and beseeched Goddess to grant me the strength of a stone.

The jovial giant wrapped his hand around mine. I pushed against him with all the might Goddess had given me. The stump sank into the soggy earth. I strained until my gums bled. He did not flinch. My strength waned. With the slightest heave he flung me across the campsite into fresh mud.

“Strong.” He propped me on his shoulders like a child. “Many sons you will have.”

Everyone agreed. A dainty girl brought us mead. For two days we sang and drank and laughed. On the third day, our laughter was interrupted by a rustling among the trees. Everyone quickly took up arms, so I shook myself sober and did the same.

I heard the enemy before I saw them. A band of brigands loosed arrows from above then descended from their hiding places. The men surrounded the women and young and fought valiantly with whatever they had. Herryck had his strength, Ambroise had his cunning, and I had my training.

My swordplay had always been mediocre, but when combined with my calligraphy it became a dizzying dance of parries and ripostes. With subtle illusion, one blade appeared to be many. My attackers lunged timidly, and I struck true. Their courage dwindled with their numbers, and before long they made a swift retreat.

That following morning, we returned to our drinking and laughing. A few of the elders of the clan offered their daughters to me in marriage. I politely refused. There was only one woman for me.

We shared stories of our pasts and dreams for our futures. Herryck yearned for the city life—the sight, the sounds, the women. I told him I meant to reclaim the love that was taken from me and a wisewoman had said if I returned to her with solamber resin, among other things, that she would show me how. His shoulders slumped and silence fell upon the entire camp like a summer fog.

Herryck told me his brother died long ago trying to harvest the resin. He pointed to the southwestern sky where trees appeared to rise into the clouds. I had not noticed them before, as the canopy of the forest along the road we travelled on obscured much of the sky, but as the road wound into a wide clearing their enormity was unmistakable.

Herryck said they were the clouds and atop them solamber resin bled from the branches for any to claim. If a man could topple one and lay it flat across the valley of Niashuqe it would take two days to walk the length of it. I understood the peril of my task.

We reached the valley the following morning. He embraced me like a brother who he knew he’d never see again. I told him halfheartedly that if Goddess had woven the threads of our lives together, we would see each other again someday. He smiled for my sake. I tried one last time to pay them for feeding and keeping us, but they refused. Silver was surety between strangers, not among kin.

Ambroise led us into the valley. We walked with the sun in our eyes over and under thick roots that jutted up from the earth. Ambroise negotiated every step with arthritic grace. Broken bones lay scattered about.

We arrived at a circular clearing, in the middle of which was the widest and tallest tree I had yet seen. A measure of humility dowsed my pride. For a moment, I questioned how much I loved her after all.

“Forty, nay, forty-two years since I made the climb,” Ambroise rubbed his calloused hands. “For fame, of course. Goddess, I was strong then.”

“How far did you get?” I asked.

“As far as I was meant to.” He tied a rope around my waist. “The going will be easy to start. The bark is thick and splayed so you can practically walk the first many miles. Pride will have you thinking you can climb it all at once. You can’t.”

“Alright. Alright. You’re worse than my father.”

In truth, he was better. Ambroise guzzled the last dregs of wine and filled the empty skin with water. He tied the skin to the rope on my waist along with a satchel of food, a hatchet, a rain cloak, and two empty clay jars.

“Most men fall from way up already dead from dehydration or freezing,” he said grimly. “Pride kills the rest. They keep on when they ought to turn back. Or they lose their footing trying to climb it all at once-”

“You said that already.”

“And I’ll say it again. Rest when you should. Turn back if you must.”

“Forward is the only way for me.”

“She must really be beautiful.” He looked at me fondly and I knew then he thought of me as a son, a thread of joy that Goddess have woven into the twilight of his life.

I said words sons seldom say to their fathers. “Thank you. Anymore words of wisdom?”

“Don’t fall.” He was already making his way back. “It’s a long way down.”

#

It was easy going, so easy I jogged. I started to think I could climb it all at once. I practically sprinted until the way around narrowed and I stumbled several miles up. I could still see green below, and I realized I hadn’t gotten anywhere. I kept at it until evening. By nightfall, I reached a height at which even birds did not nest. I dared to look down. The earth below had vanished. I felt myself in limbo, clinging to some ancient totem with no clear beginning or end.

Those who had made the journey before me left indentations in the tree which made convenient handles and footholds. Unable to fend off fatigue any longer, I rested on a broad branch for the night. I had a meager supper and a fitful sleep.

I woke more tired than rested. My thighs were chafed. Where once certainty prevailed, there was only doubt. I delayed my ascent till the sun was high. Slick with dew, every step became a hazard. I slowed to a languid pace. The air grew thin. I took two breaths for every step.

Rain fell from nowhere and persisted through the day. The cloak Ambroise thought to pack spared me the brunt of it. As the air left my lungs, I drifted in and out of consciousness and I couldn’t feel my fingers and toes.

It’s hard to explain, but the tree seemed to have its own kind of sentience. A sort of ancient wisdom out of which grew a certain contempt for adventurers like me. Moreover, I had the unshakable feeling that it did not want me there. I noticed faint scratches in the bark from where climbers held hopelessly before falling to their deaths. The bark of the tree seemed to contort and twist upon itself in such a way as to make it as difficult for a would-be traveler as possible. Indeed, my pace had slowed to but a few carefully considered steps at a time.

By day’s end, the summit seemed no closer. I curled up in a hollow. It was deep enough for me to recline in with my feet dangling out. Even as I rested the tree seemed displeased with my very presence. Random splinters of bark pricked my side, and rash stung my neck. I drifted into a deep sound sleep which spawned a most terrible dream of which I cannot remember one detail of other than that it was horrifying.

I felt the sun on my face and realized I’d slept half the day away. Desperate to make up time, I abandoned the worn path and leapt from branch to branch. I advanced faster but tired quicker. As I scaled the colossus, I noticed names engraved into the bark by those wishing to leave some testimony of their journey. Still dissatisfied with my progress, I jumped up and reached out for the nearest branch with abandon. As I strained to grasp the limb above, unseen barbs sliced my arm. My hand slipped. I tumbled through a web of branches. I reached out for something but could not orient myself.

My body jerked back, and my arm wrenched forward such that it popped out of my shoulder. I dangled helplessly, saved by the rope belt around my body that had got caught on an offshoot of a branch. Ambroise’s foresight had saved me again.

With one arm, I pulled myself up. My waterskin and rations slipped loose and fell to the world below. I barged into the tree to force my arm back in its place and nearly collapsed from the pain. I decided the slow way would suffice.

The path narrowed such that my toes hung over the edge. I kept my back pressed to the trunk. With my good arm I stabbed into the bark a couple of feet in front of me and crept forward. In such a way I made slow but steady progress.

Eve arrived without wind or rain, so I kept on through the night. Each step felt like my last. Every muscle ached, and I feared staying in one position for too long lest cramps seize hold of me. It was through will alone that I kept on.

Come sunrise I rested. Despite the erosion of time, I read a familiar name chiseled into the ancient bark of the tree. Ambroise du Hamuran. Below it a brief lyric had been carved.

Vain pursuit of glory

What was it for?

My eyes have seen eternity,

There is nothing more.

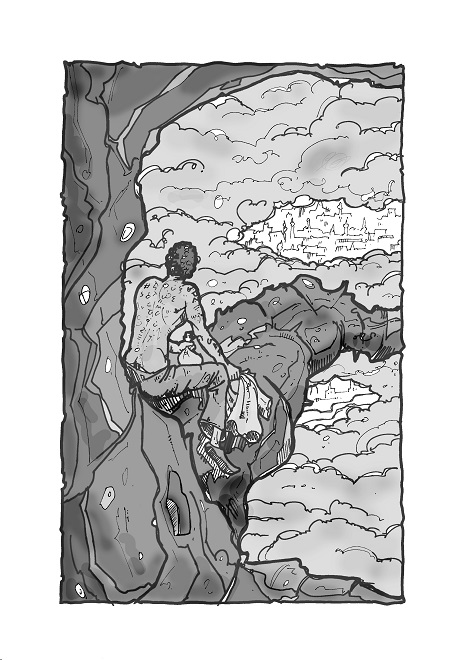

I looked out across creation and beheld a world that only Goddess knew. The valley of Niashuqe illumined by the glow of morning was magnificent. The sun and moons were fixed in the sky like tiles in a mosaic and I swear the world almost seemed round. Only Yadira could have made the moment more beautiful.

The puffs of white that I had mistaken for clouds were now discernably white leaves. I climbed without cease. By afternoon, I arrived on the verge of death but somehow feeling restored.

Without thinking, I straddled a branch and scooched along a bough covered in tiny leaves that crumbled at the slightest touch. Resin oozed from the bark that was thick as honey but tinged a violent red and fragrant with clove and cinnamon. But more. It reeked of salt and soil and sweet decay. With each breath deeper and more ancient notes emerged. It was as though the very odor of the world had coalesced into the blood of the tree. The ichor of creation.

With my hatchet, I shaved enough resin to fill both jars. As I did, the limb branch trembled as if the tree was in pain. More resin bled out. The pungent goo made my nose run. I sealed the jars before I fainted.

I had not considered the journey back but told myself that it surely could not be more perilous than the way up. I tried to crawl back to no avail. The resin had glued me to the branch like some garish ornament. I reached for my knife only to find my hands stuck to the jars. I had no way down. Or rather, I had one way down.

In such predicaments, rare as they are, one does well to stay calm. Reason, after all, is panic’s prey, and fear is a beast not known for its forbearance. I strained every muscle in my body but only managed to wiggle my nose. I applied a bit more force. The limb snapped.

I screamed and fear claimed its prize. Everything blurred. If only I could open a gash, I could summon the wind, make myself like a leaf, and maybe slow my descent enough not to die. As it was, I plummeted between and occasionally into branches.

I thought quickly and bit my tongue. Blood squirted between my teeth. As best I could, I swayed from side to side and breathed in a steady rhythm. The wind whirled around me, but I wasn’t slowing down enough.

I shimmied until my sides burned. I could not see the earth below, but I knew it was near as the sounds of forest returned. An updraft began to kick up underneath me and slowed my fall but not enough. This was the end. I closed my eyes and readied for death’s embrace.

A leafy and wooded embrace it was. I sunk into a bed of foliage. Voices surrounded me. Joyous as they were, they could not have been the voices of the dead.

“He’s alive,” one said.

“How about that,” Ambroise replied.

They dragged me out of the kindling. I couldn’t move. Ambroise and another man loomed over me with shovels. Loosely pack soil and leaves encircled the base of the tree.

They wheeled me away to a nearby village. The few days we spent there I vaguely recall—the medicine woman who scraped the resin from my body without tearing too much skin, the pretty innkeeper who fed me my meals, Ambroise settling bets with various parties.

On the third day, I was strong enough to walk. Ambroise and I departed with a wheeled cart and sturdy desert oxen to pull it. We journeyed northwest for a few days until we reached the river’s source and made camp. We fished for supper.

“You bet that I would die?” I asked.

“Aye.” He rattled a jar full of coins. “But I also bet that you wouldn’t.”

“Always hedge your bets.”

“I lost my first wife and my father’s inheritance before I learned that lesson.”

“Wisdom is folly’s offspring.”

“Aye. But it is the youngest of her brood. Born only after misfortune and failure and loss. And heartache is eternally its twin.”

He hid his face, but in the water’s reflection he could not hide his shame. My reel dangled in the water. Nothing bit. I rolled over and went to sleep.

#

We journeyed north. The valley turned to desert. Tufts of spiny grass sprouted across a sea of dunes. Gangly shadows stalked us from a distance. In the pitch of night, with their narrow gazes and sloped postures, they seemed vaguely reptilian. The light of dawn revealed them to be as human as Ambroise and me. From their trenches dug into the sand, they patiently waited for us to die.

After a day’s wandering, Ambroise decided to approach them quite naked to show he was no threat. A gaunt man, skin gritty and golden like the sand itself, came to meet him. He too was naked.

They spoke no words but conversed in intricate poses and big sweeping gestures. I had never seen this strange duet, yet I understood. Like calligraphy, it was an unspoken language, and a truer one for it.

Ambroise returned. “He said-”

“North and do not veer,” I said. “Five days more. Six mayhap. The sand will turn to stone beneath you. Among the mountain peoples, it is said that there are ogres.”

“Aye… that was the gist.”

Ambroise dressed. We carried on.

With no discernable landmarks, the constellations became our guides. Oleric stood astride the great blue rift in the night, his enchanted broadsword pointing true north. By day, blinding heat cast cruel illusions. Visions of Varushe and all its carnal splendors shimmered on the horizon forever beyond my reach no matter how far we rode.

The terrain rose higher and grew more rugged. On the fifth day, it came to pass that the sand beneath us turned to stone and cold air shattered the mirages of the desert. Tall mountains hastened sunset. From one peak rose a column of ash.

The winding pass led us around to the volcano at its center. Man-sized cairns stood around every bend. We heard music and running water. At last, the pass spilled into a sprawling city carved into the mountains themselves.

I had never beheld such a wonder, yet I knew it from the fables that the midwives told me as a child. Um’Alma’Talhad’Naddim. The place Goddess forgot. It was a pristine land, sheltered from rain, wind, and time itself. Waterfalls cascaded from the highest peaks and pooled in the hollows where children frolicked.

Mossy tangles wrapped around every edifice such that a canopy of shade covered the walking path. Painted reliefs were etched into every inch of the mountains. The people paid us no heed. They had no interest in our coins nor did we have anything to barter with since there was nothing they lacked. The smoking volcano let out a low burp.

“I wonder where the ogres are?” I gave a wry smile.

“Well,” Ambroise grinned from ear to cauliflowered ear. “Best of luck.”

“You aren’t coming with me? They say ogre tusk powder is an aphrodisiac.”

“Do I look in need of assistance?” His bones popped as he ambled off.

I set off toward the mountain. The mountain was tall but sloped gently and the path to its summit was well trodden. The peak parted down the middle. I climbed over the lip and slid into the crater at the top. Lava bubbled around the rim. A rune covered door rested in the center surrounded by steles with identical symbols carved into them.

I studied them for a few minutes and pivoted each pillar such that the symbols matched those on the stone door. The basin split apart. Lava flowed between the fissures and unseen gearwork began to crank. The doorway slid open with mechanical ease.

I descended the of steps into the mouth of the netherworld. The stench of putrid flesh permeated the dark. The residual glow from the lava that filled the depressions along the walls dimly lit the chambers. Piled upon an altar along the far side of the room were the butchered carcasses of animal sacrifices. Misshapen shadows flitted in and out of view as grunts echoed through that forsaken shrine.

I pursued the grunts through circular passages that all connected somehow. Sounds came from everywhere at once. I searched room after room but found only the gnawed limbs of cattle.

The groans multiplied. I followed them back to the main chamber. A heavy silence filled the place. I raised my cleaver. A grotesque shadow with four arms and tusks like tree limbs covered the wall in front of me. I whirled around. Nothing. Ogre or apparition? Both thoughts filled me with dread.

The groans returned, more than before. Something nipped at my ankle. I grimaced. Shadows darted here and there. I felt another burst of pain, like being jabbed in the side by a blunted blade. I followed the shadow until I cornered it. Then it vanished and swallowed me. I stabbed behind me without looking and heard a tiny whelp.

I turned around and saw a hundred frightened eyes looking at me. Ogres. A horde of them, each no higher than my knee. I laughed hysterically. In every fable I knew of ogres, they were colossi with tusks as long as spears with an appetite for virgin flesh. The truth was somehow more preposterous.

They let out a collective roar. I roared back. They flinched but did not break ranks. I reached out to grab one of them, but the others nipped at my hand. The horde moved with one mind. They flanked me and forced me to retreat into the corridor. I ran backward with no sense of what was behind me.

I stumbled. The ogres swarmed me, biting and jabbing with their tusks. I slashed wildly and sliced one of them. The creature whelped, and its brethren retreated. They were ferocious together, but alone they were vulnerable as rabbits. Ornery rabbits with sharp tusks, but still.

With abandon, I leapt into the horde. They scattered as a chased them around. One of them, smaller than the rest and with a crippled leg, fell behind the pack and I managed to wrangle it in my grasp. Its brethren clawed at me but soon gave up the struggle and abandoned their kin.

I held the creature aloft by its stubby leg. It tried to squirm free. I couldn’t help but chuckle. I lifted my cleaver. The creature squealed. I pitied the beast and let my hand drop. No sooner had I done so, it stuck me in the side with its tusk and tried to scurry away. I snatched it up by its tusk. It cried out for mercy. I swung my blade.

I emerged from the temple with the hacked off tusk and an amusing story and made my way back to the city before sunset.

Ambroise and I dwelt among them for many weeks. I found a miller who ground my tusk into fine powder and promptly stole a pinch for himself. We soothed ourselves in the scalding hot springs. Every ache I ever had vanished. They gifted Ambroise exotic spices and sumptuous robes and precious stones. Our cart overflowed with riches.

We departed the way we came. Soon the mountains faded beneath the horizon and in my mind it all seemed a dream. We carried on northward at Ambroise’s insistence. Far from civilization where only burrowing things lived, the stars reigned sovereign. Winter arrived and brought snow with it.

“Are you certain we’ll find moon stones here?” I drove our cart.

“Nothing is certain,” He stretched out atop a bed of herbs and spices. “But it is said that on the longest night, in the northmost reaches of the world, when both moons are full, moon blossoms bloom across the snow plains. And that night is a month from now, so you ought to pick up the pace.”

I sighed and kicked the oxen into a cantor across the hills.

We kept at a steady pace for weeks. At last, the hills flattened, and the riding got easier. Tall flowers with thin green stems and drab petals covered the plains. Both moons hung high and full in the twilit sky.

We lay beneath the stars and waited. Ahzdaya emerged, the primordial dragon who drove Olheric’s people from their ancestral homelands. His barbed tail swiped across the eastern sky and his wings spanned the night.

“Did you really see a dragon all those years ago?” I asked

“I see one now,” Ambroise gave me a side eye.

“You know how I mean.”

“I believe we imagine pictures in the sky to give shape to our fears.”

“But men are just as afraid of what they see as what they don’t. The snake among the flowers. The advancing army.”

“Nay. It’s the venom in the bite or the point of the enemy’s spear they dread. Most of all we fear what we can’t see in ourselves.”

There was nothing in me that I feared, yet I couldn’t help but wonder what others saw in me that might horrify them. I pondered that thought as I slipped into a calm sleep.

After a time, Ambroise jerked me by the collar. “Look,”

The flowers unfurled their petals revealing a pair of pearlescent stones that looked like both moons in miniature. I walked up and looked upon them. It is said that moon stones are the remnants of creation, all that was left over after Goddess weaved the world into existence. Their beauty moved men to incurable tears and delusions of grandeur.

They radiated an unnatural light and seemed to contain a life of their own. I reached for them. My hands froze but not from the cold. I had the strange sensation that I was committing sacrilege.

As I stared at those glowing orbs, my emotions moved on their own and tears welled in my eyes. Lust stirred within me, a deep yearning for that which I had no right to claim. I reached desperately but I simply could not grab them. Something deep inside me stayed my hand.

“Do you mean to stare till springtide comes?” Ambroise asked.

“I can’t.” I said. “It’s like stealing.”

“You’ve stolen plenty. I’ve seen you.”

“Not like this. I just can’t.”

“Alright then.”

Ambroise pulled out a kerchief, gathered the stones, and returned the scarf to his pocket. His sauntered off whistling a shanty.

“An armada.” Maniacal thoughts filled my head. “We could sell these stones. I could buy a fleet and fill its decks with sell-swords. I could siege Alma’Riha in a fortnight.”

“Armadas? Fleets? I’ve got enough for Chandra’s villa,” he said. “You can have the rest lad.”

Indeed, if only I could take hold of it. I stayed transfixed on the countless stones before me through the endless night. Come dawn, the petals shriveled and the stones turned to dust. My lust subsided and I remembered myself.

I walked away and climbed into the seat of the cart. “Ambroise, I thought you were a great man. I was wrong. You’re a decent man and that’s a much rarer thing.”

*

After scaling the summit of the world, surviving a living island, and felling an ogre in the bowels of a volcano, the rest of our scavenger hunt proved mundane.

We retraced our winding journey and after four months we arrived back at the port village. A barge ferried us out into the deeper water where Ambroise’s ship was anchored.

The ship felt a knot slower, weighed down with our hard-earned wealth. Spring had arrived, but the remnants of winter remained. We sailed southward into a stifling wind. We dropped net and trapped a hermit nautilus with the pollock. Ambroise pried the creature from its spiral shell and harvested the bile sac. A week later, we stopped at a village and bought a dozen plematines from a fruit stand that were still on the vine and about month from ripening.

We sailed on. All that remained of my scavenger hunt was a beautiful lie and piece of my heart, two damnable riddles that I stayed up day and night trying to make sense of. We spent the weeks in solitude. Summer neared. Beggar’s Bay loomed on the horizon.

“Still ain’t figured it out?” Ambroise said.

“Please, enlighten me.” I squatted in a corner of the ship.

“Beauty is true. Lies are false.”

“Obviously. It’s a contradiction.”

“Precisely.”

I had an epiphany. “And what of the other one? A piece of my own heart.”

“What is a heart? A vessel. A container.”

“Where we keep those things we cherish most.”

“Indeed. Now I must go see Chandra, for she is the object of my heart which has been gone from me for too long.”

I grabbed hold of him. “We must go.”

“As soon as I see my wife.”

He tried to pull away, but I would not let go. For the first time, I sensed anger in him. I fell to both knees and kissed his wrinkled hand like the father I wish I had.

“I need you,” I said.

He slumped. “You got silver enough to find anybody who can get you whatever you need to get wherever you mean to go.”

“No amount of silver is worth a piece of my own heart.”

“Is my life not my own.” He sighed. “Sem Uhn Waya. Goddess weaves as she will. I am but a stitch in the tapestry.”

We sailed on.

*

Rain is what Goddess willed, a ceaseless downpour that soaked us to the marrow as we sailed east of the archipelago. On the third day, Goddess, wove a wind that upset the sea. A chill seized Ambroise. He hugged himself for warmth and refused to hold down anything I gave him to eat.

“Amarantha can heal you.” I had only words to soothe him. “I swear just a few days more. If the winds let up.”

They did not. Days became weeks. Ambroise grew frail.

In the middle distance, I spotted a familiar craggy outcrop. I cut a gash across my arm and made desperate motions to beckon the waters to part. Before long, I felt another presence working in harmony with me. The rain broke.

I pulled as she pushed and pushed as she pulled. Miraculously, the water receded and an opening appeared. I had Ambroise carry my possessions while I carried him. He seemed to weigh no more than a bag of straw.

“I don’t want to burden you lad,” he whispered.

“Save your breath,” I said.

I stepped off the boat and onto dry land. The sloped path descended into a darkness that gave way to dim light.

“You’ve returned,” Amarantha said. “Impressive. But have you brought what I asked?”

“A hanowha scale. Ogre tusk powder finely ground.” I laid everything before her. “Moon stones. The ink sac from a hermit nautilus. Solamber resin. Ripe plematines.”

“Exquisite.” A spectral hand snatched the fruit, ripped the rind apart, and bit into the tart flesh. “But this was not all a requested.”

“A piece of my own heart.” I knelt beside Ambroise. “A man nearer to me than my own father.”

“An aged creature.”

“Age is but a function of time and in my experience, it only adds to the value of things.”

“Wise words, boy. Still, there was one thing more. A beautiful lie.”

“But you are already here.”

“You call me a lie?”

“I call you beautiful, but you are not as you seem.”

At last, Amarantha emerged from the shadows wearing devilish grin. “Well, a lady must have her secrets.”

“But will she have me as a disciple.”

“Anyone who would risk their life questing after such trifles must truly be deranged or in love,” she said.

Ambroise wheezed. “Proof of one is often evidence of the other.”

“True indeed.” She cackled. “Very well, Larohd du Masiim. You shall be my fledgling.”

My heart leapt. Ambroise coughed a pitiful cough.

“Help him,” I begged.

She shrugged. “He is a piece of your heart. Not mine.”

“Then I’ll do it. Just show me how.”

“Very well. It is time for your first lesson.”

Ambroise’s hand slipped from my grasp. His breath grew shallow. Amarantha knelt and handed me a long dagger, not the kind for doing calligraphy.

“No.” I swallowed my anger. “I will not kill this man.”

“But you must have your heart’s desire.”

“This man is my heart. He has been my mentor and confidant. My father and friend.”

“Yes. He lived for your dream. Either we live for our dream or die for the dream of another.”

“He had dreams. A villa in the hillside. Orchards. Garden. Flocks. He and his wife.”

“He loved her dearly.” Her eyes narrowed to slits. “But not as you love that which you desire. You must tell yourself that your dream is greater so it must live. To have your heart’s desire other hearts must be broken. This is the primordial truth of calligraphy.”

Ambroise grew cold. He wasn’t long for this world. It wouldn’t be murder, I told myself. It would be mercy. Still, I stood motionless. Amarantha held my hand such that I could not pull free.

Ambroise was my heart, but only a piece of it. The rest of it was for Yadira. Her I could not sacrifice. A piece of me had to die. Sem. Uhm. Waya. I said those words over and over as I raised the blade above my head. Ambroise sighed a meager breath and closed his eyes. I closed mine too.

________________________________________

Caleb Williams is a part-time architect of fictional worlds. His fiction has appeared in Intergalactic Medicine Show and previously in Heroic Fantasy Quarterly.

Simon Walpole has been drawing for as long as he can remember and is fortunate to spend his freetime working as an illustrator. He primarily use pencils, pens and markers and use a bit of digital for tweaking. As well as doing interior illustrations for various publishing formats he has also drawn a lot of maps for novels. his work can be found at his website HandDrawnHeroes.