THE DREAMS FROM THE BARROW

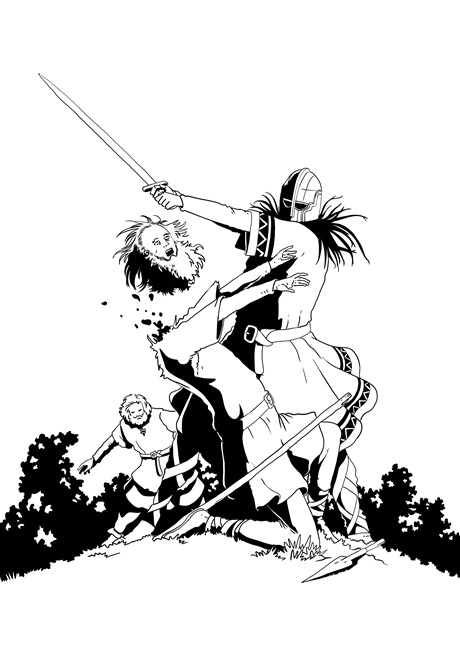

THE DREAMS FROM THE BARROW, By Harry Piper, artwork by Miguel Santos

They came to me like this –

As a young child I had gone roaming through the forest one summer afternoon – we’d finished our labours for the day and father said we could do as we wished. My mother had warned us not to go far, and we promised not to. My siblings went to play by the river, but I preferred the cool shade of the woods.

Our village is surrounded by forest on the south and western sides, where the hills begin to climb and the ground sprouts roots and stones to catch the feet of the unwary. We have ash and beech and a handful of oaks, and we used them if ever we needed to mend a fence or weave a basket.

I knew of no legends concerning the forest – there were no outlaws, monsters or ghosts supposed to lurk beneath the boughs. You could have crossed it in less than half a day. I did not fear to walk there alone.

That day I wandered without aim or purpose. I sang a little and picked up a handful of stones which I threw at shapeless things in the undergrowth. The shadows had grown long, and the light was bright gold on the green leaves. I felt lightheaded and merry.

I spotted a rock that jutted ungracefully from the earth like a broken tooth and flung a smooth dark stone at it. I watched it arc through the air and strike my target with a satisfying noise. Pleased, I went to retrieve my missile.

Whatever become of it I do not know. I picked my way through a series of roots that lay on the ground like dark strands of hair, clambered over a stone – and found myself suddenly confronted by a mound of grass-covered earth with an open doorway formed by three pieces of white stone. A barrow.

It did not make any sense – I should have been able to see it from afar. A hunter, a herdsman or another child should have discovered it decades ago.

Fate had its hand on me then, though I did not know it.

I was surprised but not afraid. I was young and innocent and curious. I wanted to see what was inside.

What I remember clearly – before the darkness – was a little tree bright with hawthorn near the entrance, and the sound its branches made as they scraped the stone of the lintel.

I was not afraid. It was summer and I was young.

When I emerged, it was dusk. My skin was cold and covered with sweat and there was dried blood on my hand from a little cut. I felt dazed and shaken.

My memory was a whirling mass of broken images. I remembered a Face – an unmoving, glittering visage of metal with hollow eyes and mouth topped by a great helm.

It had spoken to me, though it had no tongue with which to form the words; I had felt it inside my head. It had wanted something from me. An offer was made with violent desperation.

I couldn’t remember how my hand was cut. That memory, like all the others, was swallowed up in mist and darkness.

I staggered home. My mother and father were relieved to see me – I had never been one to wander far from the hearth, and to stay out until the sun was almost below the horizon was unthinkable to me.

They were horrified at my paleness, the way I slurred my words and my bloody hand. They urged me to tell them what had happened. I told them I did not know.

(It was not wholly a lie – I was confused at what had taken place, and when clarity came, they had ceased to question me.)

I don’t think they believed me, but I was not beaten or scolded for it. I slept in their room that night.

The next morning my father and the men of our village took up bills and went round the boundaries of our village, searching diligently for a beast or stranger. But they did not find anything.

My mother tried to question me again that evening with great gentleness and it upset us both that I could not properly answer her.

My siblings tried to question me, too, with clumsy attempts at kindness, but I could not tell them anything, either.

I understood that they were all acting on my behalf, for something I had suffered, and I didn’t like it – all I wanted was for the thing to be done and buried.

And it was, eventually, for the men had found nothing amiss and I seemed quite fine after a day of rest. My father said that I had probably fallen and received a blow on the head. My mother agreed, though she warned me never to wander alone in the woods again.

My cut healed. I heeded my mother’s instructions. The other families forbade their children to walk in the forest and were obeyed, for the most part. I did not see the barrow again until much, much later.

But I had been given something from it that would mark my life indelibly – the dreams.

* * *

They started soon after my encounter with the Face in the darkness. I knew that was their source, though I could not explain how, or why they were sent to me.

In them I was someone else – a grown man, with all the strength and splendour of maturity.

I sat on thrones of oak and drank mead in golden halls with my shield brothers. I rode a great horse in full armour as fields and homes burned around me. I slew foemen in glorious battle and carried off their folk into captivity.

I made bloody sacrifice to nameless gods in secret groves. Men knelt before me and swore to serve me.

Each dream was as distinct as a painted picture. I smelled the smoke. I tasted the mead. I remembered the songs. They as were real to me as any of my days in the waking world.

The dreams were with me throughout my life, sometimes visiting me once a week, sometimes once a month – but they were never wholly absent. I yearned for their coming and lamented their going. At least, at first.

Time passed, without incident. I grew taller, stronger, older. We buried two of my siblings in the churchyard after fever took them. My father lost a foot when a cart ran over it in a town at market time. I chased after girls and was chased in turn. I was no more or less than other men.

But I had the dreams.

I prized them above all else, for a peasant’s life is a hard one, full of toil and labour. Some folk sustained themselves, I knew, through nursing hidden loves, hopes or hatreds. I had something far better.

In my dreams, I had a kingdom of my own. In that strange dark land, caught only in scattered glimpses, I was no landless peasant, bound to the land and the plough. I was a man of wealth and power. I feared nothing and no-one. I wore a crown on my head and a sword at my waist.

And to tell a single soul of any of it was, I knew, to throw it all away.

For they would never understand it – friends, family, or neighbours. They would call it madness at best and witchcraft at worse. They would, perhaps, even try to cure me of my condition, and I could not allow that to happen.

To keep a secret is not so very different from a lie, I think – and perhaps more dangerous. The very heart of me was walled with iron, and even those who loved me the most would dash themselves to pieces against it before I let them in.

And perhaps it would have remained that way for the rest of my life until old age took me. I would be a man the same as any other but for the secret in his heart – another life glimpsed in moments of slumber, and a strange, confused, and frightening memory of a Face in darkness.

But on an autumn evening of my seventeenth year eight strangers came to our village. Because of them, I would remember what had transpired in the barrow – what had been promised and never given. Because of them, I would become known as a hero. Because of them, I would gain everything and lose everything.

* * *

In the spring of that year, we heard stories from travellers on the road that a band of outlaws were abroad in our county. Wild men who slew and stole without remorse. They’d killed a family for a sack of flour and hung a peddler for his boots.

At first, we were on our guard. Our reeve organised patrols for the day and watches for the night. We kept watch with club and bow close to hand. At first.

We watched, but of the bandits there was no sign. As the days and seasons wore on with no incident, we became complacent. The patrols went out rarely or not at all. Watchmen fell asleep and were not chided for it. Weapons were left at home when it was time to put shoulder to plough.

I myself took little thought of bandits. I took little thought of anything but my own troubles. My life was too full to think of anything else, for my sister had been married to a clerk in a market town and my brother had left to become apprentice to a shoemaker. I alone was left to assist my mother and father with our field.

I fear I was no easy companion to them. In truth, I was becoming a most bitter young man, held in the grip of a simmering, barely concealed anger at the condition of my folk and myself – all of us ignorant, poor and of no account in the world.

I was ashamed of our state, though I had known nor had any right to another. I had no cause for it but the dreams.

In my days I knew nothing (or so it seemed to me) but toil and weariness and poverty. Nothing lay before me, and nothing would be left behind at my going. There were ten thousand like me and all of us the same.

Yet at night I was taunted by visions of a life full of power, wealth, and glory– a life that offered terrible, wonderful purpose. A purpose I could never touch.

There were days when I would actually weep upon awaking. Daylight brought me nothing but despair.

My parents saw my hurt but did not know how to help me. They tried to speak to me, but I could or would not explain my sorrows to them.

What happiness there was came from Rowena.

I had spent much of the year courting the miller’s daughter. She was tall and graceful with red hair and pale blue eyes with a laugh that made you want to fall at her feet. Half the village was in love with her, but for some reason I won out where others failed. She and I went walking in the woods and danced together before the fires at harvest time. She was kind, and gentle, and clever, and I never knew what she saw in me.

But her family had wealth – a little, but enough. Her family had wealth and mine were but simple ploughmen.

Her father would never consent to a match, as she had told me many times with a sad smile that seemed to cover the world in shadow.

She loved her father too much to leave or wound him. Her mother was gone and he was alone. That was the curse of it – if she had been a woman that loved less, she might have been mine, but I’d have never loved that woman as much as I did Rowena.

Our love would come to an end within a year or two. She would be married off to some other man with riches and kindness enough to satisfy all parties. I would wish her well on the day and that would be that.

And if not for the dreams that whispered of another life, I could have resigned myself to it.

My mind was drifting from the grasp of reason. I took to wandering the boundaries of the village on nights when the moon was bright and full, muttering to myself and clasping my hands with sudden, violent movements. Bitterness, desire and rage were like blazing fires in my chest.

Fate had its hand on me again, however – for on the evening when the outlaws slipped into our village like wolves into a paddock I was not at home. I was out in the dark, cursing my fate and praying for an end to my troubles.

And it was granted, after a fashion.

That night, it was the screams shook me from my misery. Startled, I looked back towards the village and saw swift dark shapes moving down the street.

Doors were forced open and bewildered people thrown out into the cold night air. As I watched, someone tried to throw his assailant off only to be struck on the head with a club. The crack of it echoed across the field.

For a time, I did nothing but watch the chaos unfold. Shock had frozen me. When thought returned I had no idea of what to do. I thought of my mother and my father and Rowena. I moved towards the village in a low crouch, hoping that some opportunity or sign would present itself.

By some miracle I was not spotted. I came to the end of the street and lay prone at the bottom of a wattle fence, looking towards my home.

My mother and father were in the mud of the street, the same as everyone else. They were crouched down in the mud clutching one another, watching helplessly as strangers plundered our home.

For a strange moment I did not recognise them – instead of my mother and father, I saw an old woman and an older man, frail and lost. Something departed from me in that moment.

I cast about for Rowena but could see her nowhere. There was a man face down in the dirt with blood pouring from his broken skull – my first time seeing a man slain.

I counted six outlaws. They looked more beast than man, and every one alike – thin and snarling faces with lank hair and matted beards. The fellow I took to be their leader was a red-haired giant of a man who alone of all of them wore a mail shirt. He had a sword at his waist.

He had a gentle, indulgent smile on his face as he watched his men ransack the homes of folk who had little and would soon have even less. Chests, clothes and coins were flung out into the street; the hard-earned fruits of years of labour sneered and mocked at by men who stuffed their pockets with anything that glittered.

Soon, I knew, they would turn on the women. It was only a matter of time.

The red-haired man wandered up and down the street like a lord in the fields of his tenants. He passed my father, and I watched as he gave my father a kick without even deigning to look down. My father curled up as my mother flung herself over him. A scream rose in my throat.

The outlaws were outnumbered three to one by the menfolk of our village, but they were nought but simple peasants still half-asleep and frozen with terror. They sat in the dirt with blank faces while the women did little but scream and the children did little but cry.

I admit that there was a part of me that was embarrassed and ashamed by their helplessness. By their weakness.

The lord’s manor was an hour’s run away. The nearest village twice that. I cast about for a solution and found nothing. I wept in helpless rage.

But then I remembered the barrow.

An offer had been made, I suddenly recalled – an offer of power and strength. I had not taken it but neither had I turned it down. A strange voice in my mind whispered that it was my only hope.

I rose and ran back over the field, heading to the treeline I nearly made it before I heard shouts behind me. I cast a quick look back and saw two men with spears pursuing me. Then I plunged into the deeper shadows of the forest.

It had been years since I had entered it but the deeper in I went, the more it seemed to me as if barely any time had passed at all. My fear, my frustrated anger and even my concern were all fading – instead, a surge of excitement seized me; I felt like a child running towards a long-awaited present.

I came to the barrow. The hawthorn was there, and its flowers shone like silver in the moonlight. The screams from the village had faded, along with the shouts of my pursuers. The open doorway stood before me, beckoning me onward. Trembling, I ducked under the lintel and went into the darkness.

And I remembered everything.

The passageway inside cut down through the earth. There were no walls or side-chambers – just a long, featureless path that grew narrower and narrower. As a child I had to crouch. As a man I had to crawl on my hands and knees. The rough earth walls scraped at my head and sides. I suppose a larger man might have run the risk of becoming stuck.

But I was not afraid. I had not been afraid as a child, either. You may find it difficult to believe me, but there was a power at work in that place – you could feel the promise of it. You could almost taste it.

The tunnel came out into a chamber where black tree roots weaved in and out of the walls like dancing serpents. In the centre of the chamber stood a stone coffin, unmarked and unadorned.

On top of the coffin sat the Face, glittering in a beam of moonlight that struck through a gap in the roof above, unmoving and unmarked as it had been years ago.

I had thought it was gold as a child, but now I saw it was burnished bronze – and that made me desire it all the more. Gold was the metal of the fat, the idle and the weak. Bronze was for the strong.

Kneeling, I stared at it. I did not have long to wait.

You left me unsated, it said, the rough and familiar voice forcing its way into my mind like a spear through a gut. Were you afraid?

“I was,” I said. “I did not know what I wanted.”

And now? Now you have seen what I lived in your dreams? Now that you desire a woman you cannot have? Now that the foeman is at your door?

“Yes,” I cried. “I want it! I want it more than anything!”

Take me, take me, roared the Face, and I snatched it up and rammed it onto my head.

I left the barrow wearing it and holding the ancient sword I had taken from the coffin.

Both felt heavy and unwieldy at first, but with every step I took the more at ease I became. I had never held a sword in my life but I knew now that there were not ten men in all the land who could wield it as I could.

The helmet in particular seemed to grow lighter and lighter until I felt it was no heavier that a veil of silk.

I came out into the field beyond the trees and found two enemies waiting for me. They mocked me at first, calling me a coward and a landless beggar for running, but as I stepped closer one screamed and the other fell into silence.

For a few moments both did and said nothing. It was only when I laughed at them with a voice that was strange even to my ears that one recovered to stab at me with his spear.

Stepping aside, I cut the weapon in two as it passed me. Then I cut off the head of its bearer.

It fell to earth in a stream of dark blood, the body slumping after it a moment later. The other man dropped his weapon and fled. I flung the sword after him and it bit into his back. He screamed and fell. I retrieved the blade and cut his throat with the edge of it.

I could hear screams from the village. Torches were being lit. My blood was singing in my veins.

I came to the head of the street. Another man had been killed. He lay there with his stomach torn open, eyes wide, staring at nothing – Cobb, who liked to sing at the plough. There were four foemen there, three keeping an eye on the menfolk, one crouched over a woman.

I came up behind him and stuck him through the throat with a roar – my voice sounded deeper, older. He slumped over the woman – Edith, who once slapped me for striking her son when he struck me first.

She cried out weakly as the bleeding corpse collapsed onto her. When she saw me, she screamed. I laughed at that.

The other three outlaws, their backs to me, were slow to realise what had happened. One turned at the sound of my laughter. His mouth opened at the sight of me. I slashed across his face, cutting open his cheeks and hacking through his teeth – I heard the sound of each tooth striking the ground quite distinctly.

He fell. The other two rushed me. One took my sword arm in a strong, desperate grip while the other tried to stick me with a dagger. I held him off with a hand on his throat, shoving him and his weapon back. They were so close that I could smell them – smoke and sweat and fear.

I was a strong man and the Face covering mine made me stronger. I jerked my head back then drove it forward, striking the dagger man on the bridge of his nose. I felt it break. He yelped and faltered a little. Moving quicker than I would have thought possible, I snatched the dagger away from him with my left hand and drove it into the side of the brute who held my arm.

He grunted but did not fall. I might have been in some trouble, but someone was grappling with the man with the broken nose, now weaponless and reeling. Another man followed, and another, and he was borne to the ground. I drove the dagger in again and now the outlaw let go of me and staggered away, dropping to his knees at the last and wheezing.

The dagger man was being struck with fists, feet and stones. He lay unmoving beneath the flurry of blows. I moved on.

The miller lived at the end of the street, in a house larger than any others. There were three foemen waiting for me there.

(I only thought of Rowena later; at that moment I had mind only for the battle.)

The red-haired man with two others – he with a sword, one with a spear and the last with a cleaver. They had set a fire going on one of the thatched roofs and there were sparks in the air. Folk were crying out for help, children were screaming hysterically, I was coated in the blood of my enemies – and it was all quite wonderful to me; it was blessed.

The spearman went left and the other right while the red-haired man awaited me. They would have done well if I had been any other man, but the moment they could see my face clearly in the dancing flames they were both thrown off. Just a moment, but it was enough to doom them.

I struck the cleaver man with a great swing – I flung the sword back, both hands clasped on the hilt, then brought it down as if I were hewing at a block of wood. I opened a jagged red line on my foe from his neck to just below his belly – I heard the mingled cloth and flesh rip under the blow. A red cascade of gore sloughed to the earth as he died without a sound.

The spearman screamed – grief and horror mingled – and he rushed at me. I jerked back to avoid his thrust, watching the spearhead nearly cut open my stomach as it passed, and swung the blade down in response. I cut the spear in two and drove the point of the blade into his belly before he could react.

He gave out a strangled gasp and collapsed without further demonstration. He began to pray a Pater Noster, wheezing out the words one by one.

That left the red-haired man. He had his sword ready in a two-handed grip, standing stock-still in the doorway of the miller’s home. I took it for discipline at first, but as I stepped towards him he took a step back, and I saw that terror was etched so clearly on his face that he looked like a marble statue.

Contempt made me bold. I swung wildly overhand, and he parried – a tremor went up my arm but I didn’t pause. I swung again and missed. He fell back into the house and I followed.

A dog was barking and there was an old man – the miller – pleading in a corner. It was dim in there, the only light coming from the embers of the fire in the middle of the room.

My foe was an indistinct dark shape weaving back and forth in front of me, neither attacking nor preparing to attack.

“What are you?” he said. I didn’t reply. I went right and he went left, careful to keep the fire between us.

“Who sent you?” he said. He was hysterical. “I am not ready. You hear me? I have not been shriven.”

I dived over the hearth and tackled him. He fell back into the wall with a heavy grunt and brought up his knee into my stomach. It winded me. I let go of my sword and it fell to the ground. But it didn’t matter. The Face would give me strength.

Before I could disarm him, he managed to draw his blade back and deliver two awkward stabs. One tore through my shirt harmlessly while the other pierced me at the waist.

I felt hot blood stream from the wound but little else apart from that. I was deliriously happy.

I struck him on the jaw. He didn’t make a sound. I struck him on the nose and broke it. He was looking at me with wide-eyed terror. I hit him again and again. I was bleeding steadily but another power fed me strength to recompense the loss – indeed, to make me forget it entirely.

My foe seemed to shrink with every blow. Finally, he let go his sword and slid down the wall into a crouch, throwing his hands around his knees and pressing his face into his calves. He begged me not to hurt him.

What happened next, I am not quite sure. I think the Face spoke to me. It was thirsty, it told me, and it needed to drink.

Bite, bite, bite, it told me.

When I came back to myself, I was crouched over the red-haired man’s body and there was a great deal of blood on the floor, on my hands and in my mouth. The miller, who I had quite forgotten about, was screaming as he looked at me. There was movement in the room above and in the street outside- people were moving about, calling for me.

A pail of water stood nearby, and I was able to wash and spit out the worst of it. The passion of my first battle was fast fading. I felt triumphant but also tired and a little confused.

I looked down into the reddened water and saw a face like my own but not quite as it should be. I touched my cheeks, my forehead and my brow but felt no trace of the thing I had taken from the barrow.

A voice spoke to me without words. A voice sleepy, sated and yet somehow spiteful, too –

Enjoy your glory, but remember you have a service to perform. You must come to me and feed me. Do not forget it.

Then it was gone.

A door was opened from the loft and down came Rowena. She saw her father whimpering in the corner, the red-haired man face down in the rushes and myself standing wounded but triumphant. For a moment she hesitated, looking at me unsurely. But then I said her name and the spell was broken and she flung herself into my arms.

We came outside, her supporting me as I stumbled unsteadily. My wound was beginning to bite with a growing and insistent pain. Before I lost consciousness altogether there was a moment when I saw the faces of my neighbours, my friends and my mother and father as they looked at me. Wonder and horror mingled together. Then I fell into darkness.

* * *

Rowena married me, eventually. Her father was in no fit condition to object any longer and I was seen by all as a hero and protector of our village.

Not so for our first winter, however – the wound I had suffered nearly killed me and I did not leave my bed for weeks. I could barely speak and was sorely troubled by bad dreams and fancies.

The dreams of glory and power were gone. They never returned. Now I had but one, awful nightmare – where I was entombed in a stone coffin. My limbs were withered and pale. My chest did not rise and fall and there were things moving in my flesh.

In the dream, I was not afraid but furious – sick with anger. Someone had failed to aid me. I was betrayed.

The fancies I do not remember. In my fever, I am told, there were times when I tore at my cheeks with my nails, screaming that there was something covering my face. On other occasions I fell to arguing with phantoms who demanded something I had no wish to grant.

Rowena was there to nurse and comfort me through all of it. I clung to her like a lost child.

I lived. I did not go mad. The horrible dreams of the stone coffin faded.

Come spring Rowena and I exchanged vows before the altar while the priest and the village looked on (her father murmured absently to himself throughout the ceremony, refusing to even look at me). We drank golden mead in the sun and my mother wept happy tears on my neck. My father could barely speak for joy.

I was a hero. Children looked at me with wonder, women with longing and men with fear and envy. Our lord even came down from his manor to bestow upon me a purse of shillings for my gallant actions.

I took over at the mill while Rowena sat at the loom. We still laboured like the others, but we would never have to fear penury and could enjoy a little meat with our bread every now and then. I paid for a girl to live with my mother and father to assist them as they aged, and with the miller’s money he too was well-cared for.

We counted ourselves blessed. But there were things to burden us, too.

Rowena’s father was never the same. He had lucid days which Rowena treasured, but he could never abide the sight of me. I told myself I was guiltless of causing his condition, but I could never truly believe it.

And questions remained about my deeds. How had a peasant barely fit to be called a man triumphed in awful, bloody glory where battle-forged knights would have failed?

I could not answer the former, and for the latter I told them that I had found it in the forest. This was not untrue.

Our lord looked at the blade for himself after he gave me my shillings. I watched his face as he examined it; he wore a smile that did not reach his eyes. I did not blame him.

The weapon was made of beaten iron, wickedly sharp and deadly heavy. The hilt was wrought in the likeness of two snakes who wound about one another, rising to the blade which issued from their gaping mouths. Their eyes had once been filled with jewels, perhaps, but now were hollow.

There was something disquieting about the serpents’ heads – they seemed to grin in idiot joy. The blade was inscribed with a series of tiny human heads that ran to the very point, each one displaying terror.

He permitted me to keep it – a rare indulgence for a landless peasant, and one I regretted I could not openly reject.

I put it in a heavy chest in our home. Rowena and I did not discuss it. It was like an unwelcome guest in our house.

I did not know exactly what certain folk whispered about me behind closed doors, but that they whispered I am certain. Certain conversations would die when I approached. Certain men exchanged words in low voices as I passed. Sometimes I found Rowena crying alone and cursing the women of the village for taletellers and fools.

I had not lied to Rowena but neither had I told her the truth. But what could I tell her? That I had bargained with an unseen power in a place where the dead were laid to rest? That I had taken the face of another and worn it at its own urging?

And where had it gone? I remembered putting it on but never once taking it off. But there had been so sign of it anywhere.

Another thing too – a nagging sense of guilt. I had unfinished business at the barrow, my conscience (if conscience it was) whispered to me in quiet moments. A debt unpaid.

But gradually, in spite of all, I taught myself to believe that nothing had happened. Nothing of consequence. On the night of the attack, I had fled into the woods and by pure luck happened upon an ancient sword. All else – the face, the voice – had been somewhere between a dream and a fancy conjured by terror and desperation.

It was not so hard to convince myself of this. The fancies and dreams no longer troubled me, and I lived as other men did. Or at least I tried to.

I did not like the way my father treated me with wary respect, nor the confused looks given me by my mother. My friends never spoke to me as they had done in our youth. They looked at me as if I were a proud knight, but I was just as ignorant as they were. I remained at heart dreadfully confused by all that befallen me. I had no wisdom to offer and what strength I had seemed borrowed.

It was a mask they believed in, and I began to worry that there was nothing much to the man beneath it.

Rowena could see unspoken things troubled me. But she did not ask, because she knew that I would not tell her. I was afraid of how she might react, faithless man that I was – our life was hard-won, and I would not dare risk it for anything.

The happiest moments with her were when she let me lie in her arms in bed as she stroked my hair, silence enfolding us. I did not know what to do. I had no-one to instruct me. I had no-one to protect me. But when I lay with her, I thought she knew me, and I thought that might be enough.

Then, about the time when Rowena showed the signs of our first child, in the late autumn, I suffered the return of new dreams and, with them, another great terror came on our village.

* * *

In the first dream, my mouth was full of blood, and I was crawling across a field. Cattle were lowing in alarm and the stars were wheeling above me in the night sky. I was weak but growing stronger.

I pulled myself towards a forest, fleshless fingers clawing at the dirt.

I awoke suddenly, with the sense that someone had shaken me awake. But our room was empty. Rowena murmured in her sleep. I checked all the windows were shuttered and the door was locked before returning to bed.

Come morning I heard from my father that a wild animal had torn out the throat of one of our cattle. Strange tracks had been left on the ground.

That evening I waited until Rowena had fallen asleep before I crept downstairs, took the sword from its chest, and went out into the night.

I went to the forest. The dry leaves whispered under my feet while the half-naked boughs groaned under the wind.

I went to the barrow. I crawled down the narrow tunnel. I came to the stone coffin and found it empty, the lid cast aside and smashed into pieces.

And then I crept home, put the blade back in its chest and crawled into bed.

For a week everything was fine, then I had a dream in which I was attacked by a dog as I broke into a paddock.

It was a big thing, full of life and strong, but I broke its neck with ease, tore off its head and left its entrails draped across a nearby fence.

The next day the men of the village said that either a madman or a monster was abroad. I said nothing.

More raids followed. It took poultry, dogs, and cattle. Some folk said that they could hear it walking down the street at night with soft footsteps, murmuring to itself in a strange tongue. No-one dared confront it.

They came to me, as I knew they would; begging their hero to save them once more. I took my sword from its chest and led patrols at night – a dozen or so terrified men with clubs and spears stumbling after a man who knew the creature would never allow itself to be trapped or baited so easily.

And besides, what did it care for them? Its quarrel was with me.

In my dreams, I saw as it did. I felt its desires and knew its thoughts.

The first thing it wanted was strength; it had long lain in the barrow and time had weakened it. It could get that through the drinking of blood and consumption of flesh. Cattle would do while it was weak.

The second thing it wanted was revenge on myself, for failing to abide by my oath. Its hatred for me was beyond passion – it was cold and settled thing, utterly immovable.

The third thing it wanted was, even above vengeance, a world in which everything made sense. There was immeasurable grief in the things heart – an ocean of loss.

The patrols petered out. Men looked to their own homes. I took to sitting before our door with the sword in my hands when darkness fell. I slept fitfully. I knew worse was to come, but I dared not speak of what I knew. All would be lost if I did, I told myself.

Finally, it murdered a traveling friar. I was there to witness it all in my dreams – a silent, frozen prisoner in the thing’s body, incapable of restraining it nor giving warning as it tore open the screaming man’s chest to feast on what lay within. As it gorged itself it spoke to me directly:

Soon, I will take a child. Return what you have stolen, or I will kill your mother, your father, and your wife. They shall all die screaming.

It was a relief when I told Rowena I must leave her and our home to go seek it out. To put an end to it all. Rowena screamed and wept and clung to me, begging me not to go, but I had to. There was nothing else to do.

It was truly winter by then. The trees were naked, and the fields smothered in snow. I wore a heavy woollen cloak and bore but a few days food along with the sword; I felt that it would not take long, no matter the outcome of our consummation.

The villagers lined the street to watch me leave, cheering me on. I was their champion. A hero come to deliver them from evil once again.

But their praise and their blessings fell on me like rain on stone; they loved the mask.

Things were clearer once I wandered far enough – out into the bare hills, where I could hear not a single bird and see not a single fire. I had no plan and needed none. My enemy would be drawn to me, for we could not long last one without the other.

For seven days I wandered the barren wilderness. All I saw was white and still – the world was asleep, and I and my enemy the only things awake.

I kept the naked sword in my hand and watched and listened. There were moments when I heard the crunch of a leaf or the patter of feet on frozen earth, just at the edges of hearing, or saw a great shadow cast down from the lip of a hill – but no matter how swiftly I moved towards these signs I was never able to surprise it.

The thing could see through me. I felt its presence in my mind.

I felt the anger, the sorrow, and the envy – for the first time, I saw that it envied me. For I had a mother and a father. I had woman who loved me. I had a child on the way. I had a place in the world.

It came at me in the nights when I found shelter against the awful killing winds in caves and hollows.

I built my fires and sat behind them with the sword laid out on my lap. I closed my eyes and saw through its own.

It would come to the very edge of the light cast by the flames, and it would look at me. We looked at one another.

At last light on the seventh day, we settled our argument.

It waited for me in a little clearing at the end of a winding woodland trail. I saw it from afar and went to meet it without fear.

We stood in the clearing facing each other in silence, separated only by twenty paces or so.

I saw what had once been a man of great stature and strength, which even the grave had not been able to diminish entirely. What little remained of the flesh was half-covered in soil, moss, and roots.

The fingers were no more than claws and the cheeks were hollow. It wore ancient, ruined armour with an empty sheathe at its side.

You still wear my face, it said. I wonder if you could even live without it.

“Let us find out,” I replied, and went at it.

Too hasty, too clumsy. I stabbed and I missed and it laid open my cheek with its awful fingers in one quick slash. I screamed as blood poured down my face and filled my mouth.

I backed away and it came on after me, swiping at me, claws whistling though the air, coming closer and closer to my face. Its movements were oddly calculated, and I realised it wanted to blind me.

Thief, it said. Oath breaker.

It wanted to make me crawl. To cut and savage me until I begged for an end.

Horror gave me strength and I brought the sword down over my head. It bit into the things wrist and cut straight through – the hand hanging on only by a strip of skin. It bled but only with a thin and pale stream.

It tore the hand away and struck at me with a closed fist. The blow struck me on the shoulder and nearly spun me around. Dazed, I tried to recover my wits as it rushed in to grapple with me. I stabbed at it and the sword plunged into its belly as its hand reached for my throat.

The weapon sank in deeper. More pale red blood seeped from the wound, but it gave no sign of feeling it, reaching for me still. The fingers inched closer to my throat, and it had such strength that I knew it could break my neck with ease. Death stood at my shoulder.

Then I saw, as in a dream, this risen corpse returning to my home wearing my face, receiving my Rowena into its arms as she rushed to it, innocent and unknowing.

I screamed and jerked forward, driving the sword in to its hilt and placing my neck wholly within the grasp of those terrible fingers.

Dark scarlet, cold and half-congealed, flooded from the wound and covered my hand. The claws curled around my throat and squeezed.

For perhaps three moments my vision darkened. I saw strange faces and places.

But then the grip slackened. The thing growled in my face but already its limbs were trembling, the hand falling away.

I pulled the sword out and stepped back. It clutched at the wound, but only for a moment. It stared down at the flood of red swiftly turning to a trickle, looked up at the sky, then staggered into the trees. I followed.

It didn’t make it far. It took its last breaths by the side of a still pond, black with weeds. It didn’t even look up as I approached.

I stood over it for a space – a strange hesitation gripped me. The light was dying, and it was starting to snow. It turned its head to look at me.

“But what will become of us?” it said in a dry whisper. “What will you do?”

I cut off its head.

I pressed the body into the water with my foot. It made barely a ripple. I picked up the head, my fingers gripping matted hair half-eaten with rot, and cast it in after. The water took it quietly, and I was alone.

I cast the sword in, too.

Then I waited.

But nothing fell from my face to follow after. I waited until it was near dark and a piercing wind whipped the tears from my cheeks, but nothing came. I tore at my face with my fingers until blood slicked my fingers and dripped into the water, but I could find no trace of it.

And so it has been since. I am no longer troubled by dreams, pleasant or terrible. But there have been many nights when I have awoken gasping for breath, feeling the choking, smothering grip of something hard and cold and heavy lying atop my face – something that always vanishes before I can grasp it.

________________________________________

Harry Piper lives in Wales and is constantly surrounded by too many books than are good for him. He has long enjoyed reading and writing fantasy- even more so ever since he discovered people are willing to pay him for the latter. He hopes to continue doing it for a very long time.